Listening to Land:

Imaginal Technologies,

Material Conduits,

&

Landscape Translations

Toward Perceiving Place

July 13, 2023 - August 27, 2023

Opening Reception July 15, 4:00-7:00pm

Closing Reception & Gallery Talks August 27, 4:00-5:30pm

Exhibition Checklist The image gallery to the right follows the exhibition checklist.

Listening to Land is a group exhibition exploring practices of listening in relation to place and the place-making potential of creative acts of listening, wherein to land is a verb, and listening provides a point of ingress.

Artists in the exhibition use storytelling, jam-making, woodworking, basketry, mapping, lenses, microphones, speakers, and other technologies to heighten our ability to relate to our surroundings and other beings, and to extend our capacity to perceive beyond what is visible or knowable in the landscape. Prehistoric, mythical, and contemporary techniques used by the artists help us to imagine futures in which humans are in more reciprocal relationships with each other and the broader cosmology of entities with whom we share the land.

The exhibition offers sounds, portals, and moments of suspension, aiming to inspire silence, slowness, and humility. Materials such as wood, water, stone, soil, plants, glass, metal, horsehair, and minerals act as conduits for the voices of the land from whence they came. The artists invoke the non-human presences of specific places through ultrasensitive explorations of their materials’ inherent qualities and capabilities, inviting us to pause, and reshaping our perceptions.

The works in the exhibition suggest that when one listens to land, the land reveals entanglements with intangible forces and phenomena, with buried histories and lost kinships, and with water systems. Rather than rendering landscapes that delineate land from water, human activity, or the cosmos, the works in the exhibition translate images of landscape into abstractions, experiences, revisions, and mappings that allow us to know the land through intricate and interconnected relationships.

Free public programming supporting the exhibition will include engagements with several regional artists, informal gallery talks at a closing reception walk-through, and Curated Reading List 003 in our Open Reading Room...Learn more here

The exhibition is curated by Gallery Director Alison McNulty and includes works by:

Margaux Crump

Donna Francis

Katerie Gladdys

Katie Grove

Ellie Irons

Sergey Jivetin

Kite and Robbie Wing

Fernanda Mello

Steve Rossi

Jean-Marc Superville Sovak

Susan Walsh

Millicent Young

The exhibition, programming, and receptions are free and open to the public, but some workshops accommodate a limited number of participants and require a reservation.

Can you hear me now?

Pyrite concretions and dust, copper magnet wire, copper electroformed twigs, soil, mica, salt

6 x 36 x 36”

Can you hear me now? is a series of fantastical listening devices that playfully reimagines how we communicate with—and through—minerals. Informed by early crystal radios, antique copper antennas, and apotropaic Brigid crosses, these sculptural objects merge spiritual and mundane technologies by leveraging their shared materials, processes, and traits. As a ritual installation, the individual devices create a circuit, opening a conduit that is grounded by the soil and salt circle.

Pyrite concretions and dust, copper magnet wire, copper electroformed twigs, soil, mica, salt

6 x 36 x 36”

Can you hear me now? is a series of fantastical listening devices that playfully reimagines how we communicate with—and through—minerals. Informed by early crystal radios, antique copper antennas, and apotropaic Brigid crosses, these sculptural objects merge spiritual and mundane technologies by leveraging their shared materials, processes, and traits. As a ritual installation, the individual devices create a circuit, opening a conduit that is grounded by the soil and salt circle.

For Seeing Neither Here Nor Elsewhere

Naturally holed hag stones, antique microscope lenses and objectives, engraved glass and velvet display

case

6 x 30 x 9”

For Seeing Neither Here Nor Elsewhere explores lenses and apertures as ocular portals. How we see shapes our reality. In certain folk beliefs, peering through holed stones enables you to see across the veil into the otherworld. In science, microscopy similarly reveals the invisible world of microbes. This work combines these complementary visual technologies to shift how we see—incorporating the imagination as an integral aspect of human perception.

Naturally holed hag stones, antique microscope lenses and objectives, engraved glass and velvet display

case

6 x 30 x 9”

For Seeing Neither Here Nor Elsewhere explores lenses and apertures as ocular portals. How we see shapes our reality. In certain folk beliefs, peering through holed stones enables you to see across the veil into the otherworld. In science, microscopy similarly reveals the invisible world of microbes. This work combines these complementary visual technologies to shift how we see—incorporating the imagination as an integral aspect of human perception.

Donna & June

4x5 Pinhole Camera/Archival Giclee Print

26 x 31”

4x5 Pinhole Camera/Archival Giclee Print

26 x 31”

Mercy

4x5 Pinhole Camera/Archival Giclee Print

26 x 31”

4x5 Pinhole Camera/Archival Giclee Print

26 x 31”

green lining?

Portable DVD players, wood, video

55” x 72” (installed) 13” x 10” (individual boxes)

1 minute and 15 seconds, 3 minutes and 14 seconds, 1 minute and 14 seconds

Slash and burn land clearing in Florida provides an optimal habitat for edible weeds. green lining? documents the tragedy, irony, and possible redemption of these landscapes. Rampant land development—condominiums, churches, and subdivisions— marks/mars the Florida landscape and is part of the ongoing history of the state. In the current the real estate market, developers clear land at a breathtaking pace, forest, farm or ranch land one week, strip mall and high density suburban homes the next. Bulldozers, fire, and herbicide destroy entire ecosystems. Next, a road replete with a cul-de-sac is etched into the landscape, followed by utilities and signage purposing the land into sale-able lots. If not immediately built upon, the cleared land is left to its own devices becoming a ruderal ecosystem, providing a habitat for edible weeds and creating a green lining in light of the greater destruction.

Portable DVD players, wood, video

55” x 72” (installed) 13” x 10” (individual boxes)

1 minute and 15 seconds, 3 minutes and 14 seconds, 1 minute and 14 seconds

Slash and burn land clearing in Florida provides an optimal habitat for edible weeds. green lining? documents the tragedy, irony, and possible redemption of these landscapes. Rampant land development—condominiums, churches, and subdivisions— marks/mars the Florida landscape and is part of the ongoing history of the state. In the current the real estate market, developers clear land at a breathtaking pace, forest, farm or ranch land one week, strip mall and high density suburban homes the next. Bulldozers, fire, and herbicide destroy entire ecosystems. Next, a road replete with a cul-de-sac is etched into the landscape, followed by utilities and signage purposing the land into sale-able lots. If not immediately built upon, the cleared land is left to its own devices becoming a ruderal ecosystem, providing a habitat for edible weeds and creating a green lining in light of the greater destruction.

Mapping the Managed Forest: Interstitial Sustenance

In collaboration with longleaf pine, sand pine, marsh fleabane, shiny blueberry, sparkle berry, deerberry, myrtle, beautyberry,

gallberry, red bay, magnolia, lac bugs and bees

sugar, honey, water, canning jars, pine shelving

68 x 48”

Drive in any direction away from town on an interstate or backcountry road and rows upon rows of pine trees morph into grids of pine plantations that constitute the majority of the rural landscapes of the southeastern US. Managed pine forests are economic resources with ties to private industry, but many are also part of the public trust in the form of state wildlife and water management areas that are simultaneously sites of outdoor recreation and agriculture.

Longleaf pines (pinus palustrus), once dominated pre-European settlement forests and are deeply rooted in the economy, culture and history of the southeastern United States. Longleaf pine forests were one of the most diverse and abundant ecosystems in the world--open, sandy, bright and airy landscapes that provided habitat for birds, deer, bobcats, bears, tortoises, reptiles and hundreds of diverse plant species. In the present, the organization of most managed forests abets the commodification and efficient development of timber resources.

Eccentric Grids: Mapping the Managed Forest: is a series of cross-disciplinary sensual investigations into the pine ecosystems of north Florida. Interstitial Sustenance examines the historical medicinal and culinary uses of the native plant understory that connects and supports the gridded formation of cultivated longleaf pines at Austin Cary Forest, University of Florida’s teaching forest. Foraging and preserving plants in sugar using canning technologies invites the audience to consider how practices of scientific collection and extraction shape our relationship to the land.

Interstitial Sustenance is both the painting formed by the shelving and the jars of jelly and jam, and my physical engagement with the managed forest. I began by walking the forest with botanist documenting and identifying the plants living amongst the pines. I, then, researched each plant’s natural history, surprised by the lack of information on the uses and edibility of each plant. Descriptions often ended with mention of an association of the plant with “native peoples”, but absent was the recognition of the specificity of indigenous knowledge. With gratitude, I carefully harvested needles, leaves and berries, walking and crawling amongst the plants, noticing patterns of how they space and entangle with one another and learning their strategies for dispersal and sustainability. Finally, I processed the plants into jam and jelly in mason jars recalling the history of preservation of specimens and speculating on the potentials and contradictions of what constitutes listening to, caring for, and making use of land.

Austin Cary Forest and my home sit on the ancestral territory of the Potano and of the Seminole peoples. An acknowledgment of the land is a formal statement that recognizes Indigenous Peoples as the traditional stewards of the land and acknowledges the enduring relationship between them and their traditional territories. The purpose of this statement is to raise awareness of this relationship as well as the complex histories that led to the forceful removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in what today is recognized as the state of Florida.

Special thanks to Alex Abair for botanical consultation and plant identification and the staff of University of Florida’s School of Forest, Fisheries, & Geomatics Sciences Austin Cary Forest for access and technical support.

In collaboration with longleaf pine, sand pine, marsh fleabane, shiny blueberry, sparkle berry, deerberry, myrtle, beautyberry,

gallberry, red bay, magnolia, lac bugs and bees

sugar, honey, water, canning jars, pine shelving

68 x 48”

Drive in any direction away from town on an interstate or backcountry road and rows upon rows of pine trees morph into grids of pine plantations that constitute the majority of the rural landscapes of the southeastern US. Managed pine forests are economic resources with ties to private industry, but many are also part of the public trust in the form of state wildlife and water management areas that are simultaneously sites of outdoor recreation and agriculture.

Longleaf pines (pinus palustrus), once dominated pre-European settlement forests and are deeply rooted in the economy, culture and history of the southeastern United States. Longleaf pine forests were one of the most diverse and abundant ecosystems in the world--open, sandy, bright and airy landscapes that provided habitat for birds, deer, bobcats, bears, tortoises, reptiles and hundreds of diverse plant species. In the present, the organization of most managed forests abets the commodification and efficient development of timber resources.

Eccentric Grids: Mapping the Managed Forest: is a series of cross-disciplinary sensual investigations into the pine ecosystems of north Florida. Interstitial Sustenance examines the historical medicinal and culinary uses of the native plant understory that connects and supports the gridded formation of cultivated longleaf pines at Austin Cary Forest, University of Florida’s teaching forest. Foraging and preserving plants in sugar using canning technologies invites the audience to consider how practices of scientific collection and extraction shape our relationship to the land.

Interstitial Sustenance is both the painting formed by the shelving and the jars of jelly and jam, and my physical engagement with the managed forest. I began by walking the forest with botanist documenting and identifying the plants living amongst the pines. I, then, researched each plant’s natural history, surprised by the lack of information on the uses and edibility of each plant. Descriptions often ended with mention of an association of the plant with “native peoples”, but absent was the recognition of the specificity of indigenous knowledge. With gratitude, I carefully harvested needles, leaves and berries, walking and crawling amongst the plants, noticing patterns of how they space and entangle with one another and learning their strategies for dispersal and sustainability. Finally, I processed the plants into jam and jelly in mason jars recalling the history of preservation of specimens and speculating on the potentials and contradictions of what constitutes listening to, caring for, and making use of land.

Austin Cary Forest and my home sit on the ancestral territory of the Potano and of the Seminole peoples. An acknowledgment of the land is a formal statement that recognizes Indigenous Peoples as the traditional stewards of the land and acknowledges the enduring relationship between them and their traditional territories. The purpose of this statement is to raise awareness of this relationship as well as the complex histories that led to the forceful removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in what today is recognized as the state of Florida.

Special thanks to Alex Abair for botanical consultation and plant identification and the staff of University of Florida’s School of Forest, Fisheries, & Geomatics Sciences Austin Cary Forest for access and technical support.

Apron

Basswood fiber (Tilia americana)

75 x 35”

In Objects of Power II, the inner bark (bast) fiber of a basswood tree (Tilia americana) weaves and unweaves into the form of an apron, a symbol of domestic life and women’s work. Bast fiber from species of trees in the genus Tilia was essential to the lives of my ancestors in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Norway for tens of thousands of years. Through harvesting, processing, and creating with basswood fiber in both traditional and non-traditional was I seek to connect to their lives and experiences.

Basswood fiber (Tilia americana)

75 x 35”

In Objects of Power II, the inner bark (bast) fiber of a basswood tree (Tilia americana) weaves and unweaves into the form of an apron, a symbol of domestic life and women’s work. Bast fiber from species of trees in the genus Tilia was essential to the lives of my ancestors in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Norway for tens of thousands of years. Through harvesting, processing, and creating with basswood fiber in both traditional and non-traditional was I seek to connect to their lives and experiences.

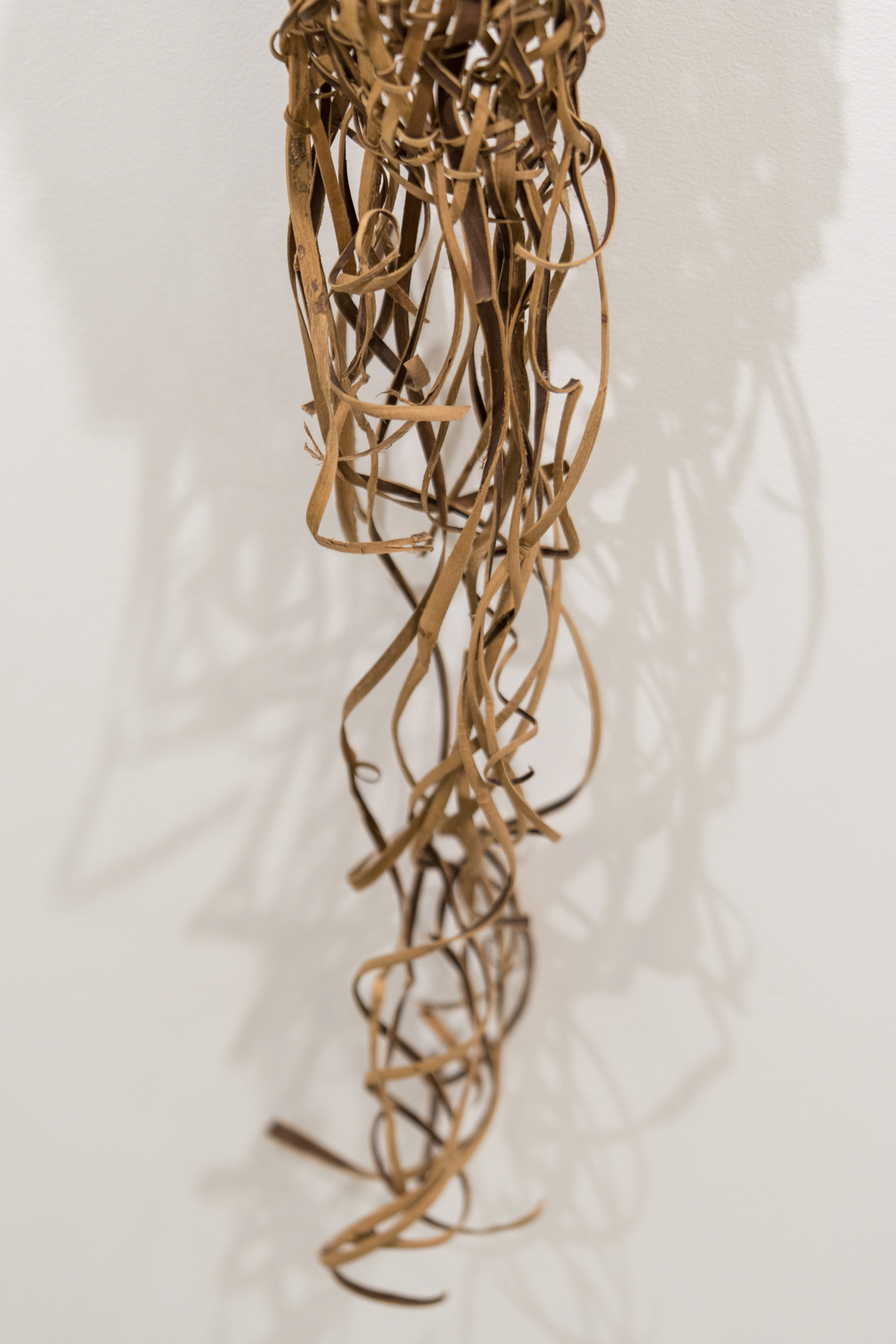

Ulmus Unweaving

American elm branch bark (Ulmus americana)

61 x 6 x 6”

In Ulmus Unweaving, the inner part of a found piece of elm bark separates from the main body and either weaves or unweaves itself in a tangle of patterns. The process of peeling inner bark can only happen in the spring and this piece represents the ephemeral nature of that short time frame. During the making of Ulmus Unweaving and related pieces I start with the pieces of bark and listen to the material as I construct it in situ.

American elm branch bark (Ulmus americana)

61 x 6 x 6”

In Ulmus Unweaving, the inner part of a found piece of elm bark separates from the main body and either weaves or unweaves itself in a tangle of patterns. The process of peeling inner bark can only happen in the spring and this piece represents the ephemeral nature of that short time frame. During the making of Ulmus Unweaving and related pieces I start with the pieces of bark and listen to the material as I construct it in situ.

Standing Form/Becoming

Black ash log and splints (Fraxinus alba)

21 ¼ x 4 x 4”

Standing Form/Becoming uitlizes the traditional North American basketry material of black ash splints in a way that collaborates with the log, and therefore the tree, from which the material came. As black ash trees continue to die off due to invasive emerald ash borer beetles this series may be my only experience working with this incredible material, lending an air of reverence to the process and the final piece.

Black ash log and splints (Fraxinus alba)

21 ¼ x 4 x 4”

Standing Form/Becoming uitlizes the traditional North American basketry material of black ash splints in a way that collaborates with the log, and therefore the tree, from which the material came. As black ash trees continue to die off due to invasive emerald ash borer beetles this series may be my only experience working with this incredible material, lending an air of reverence to the process and the final piece.

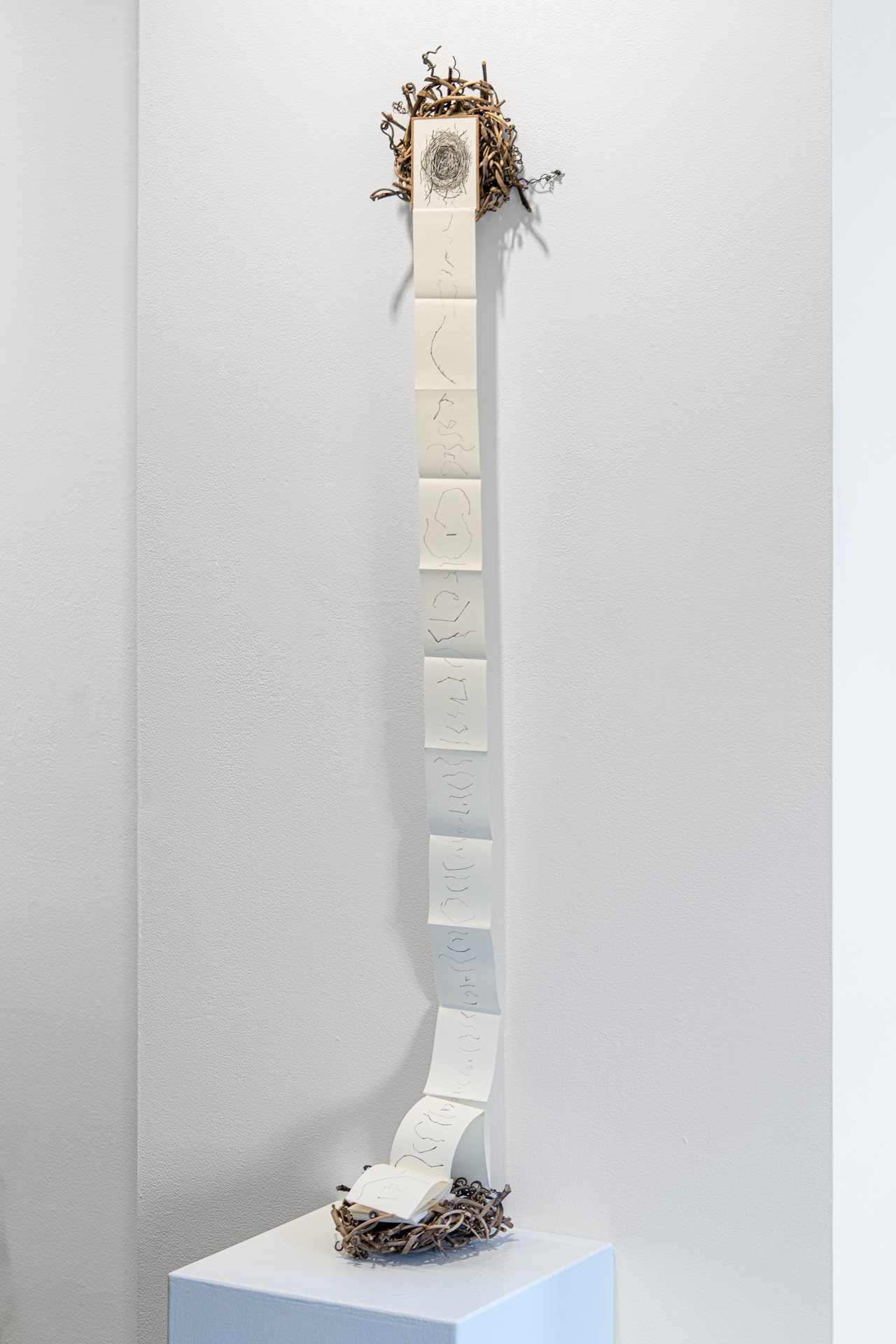

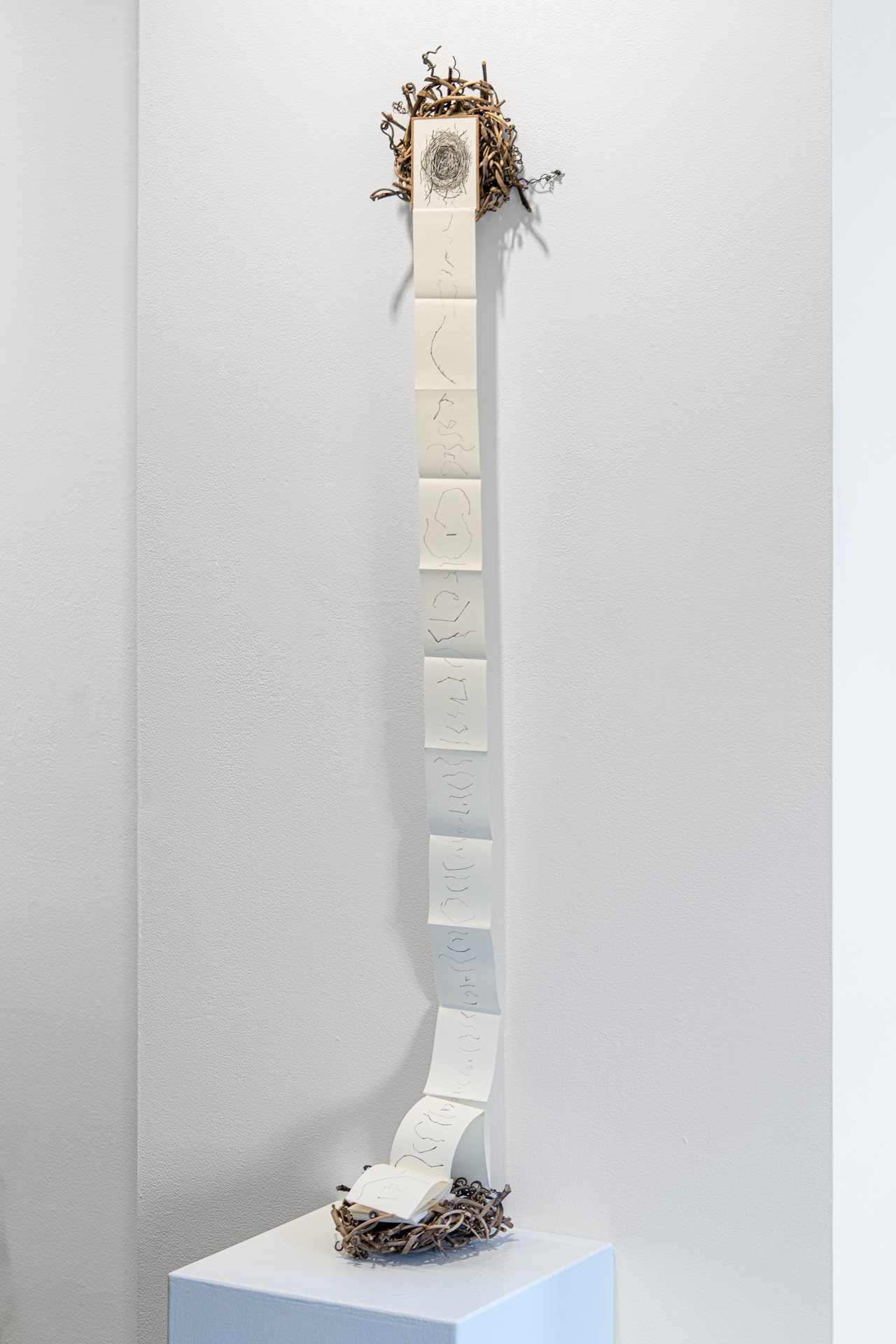

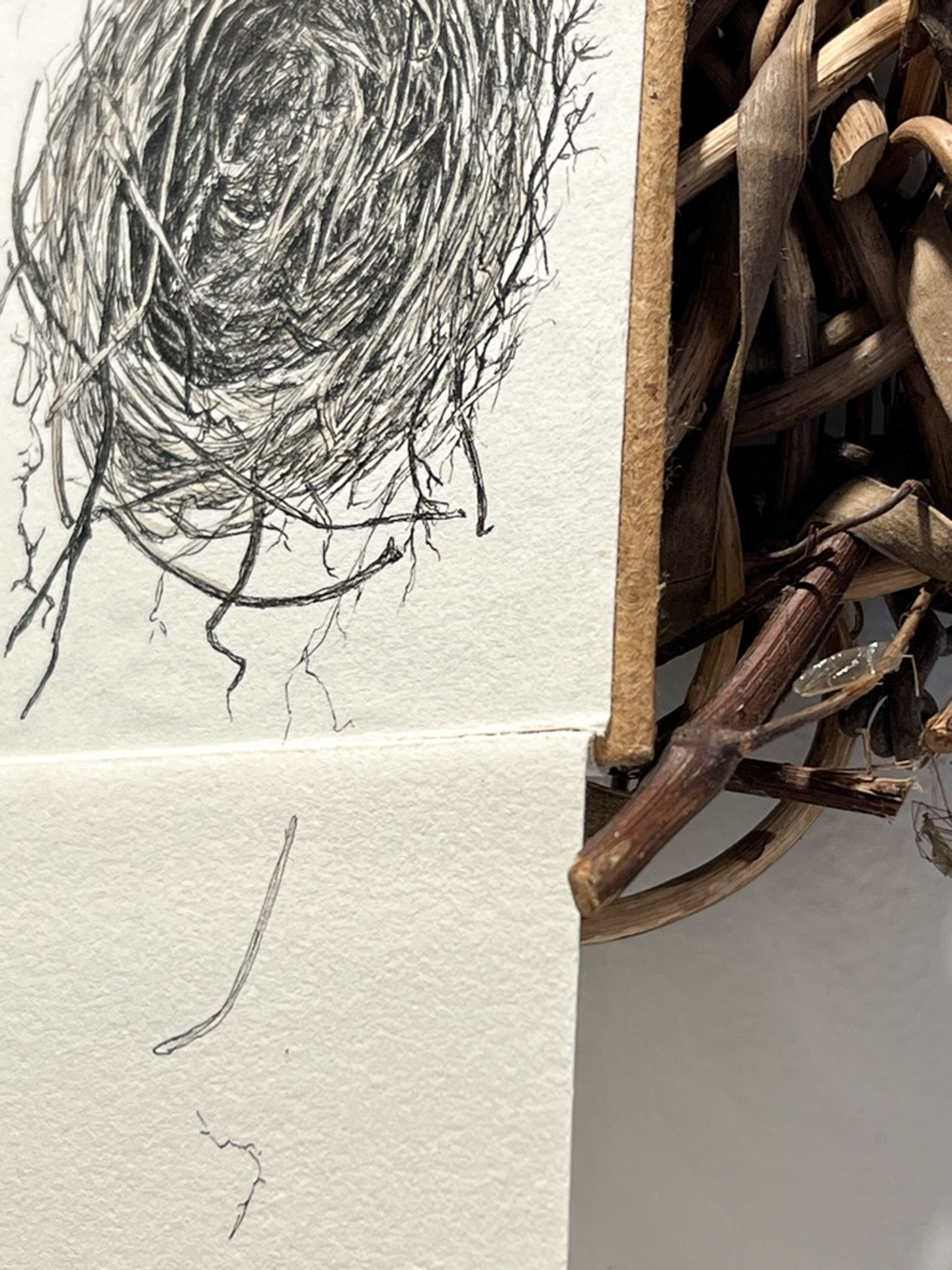

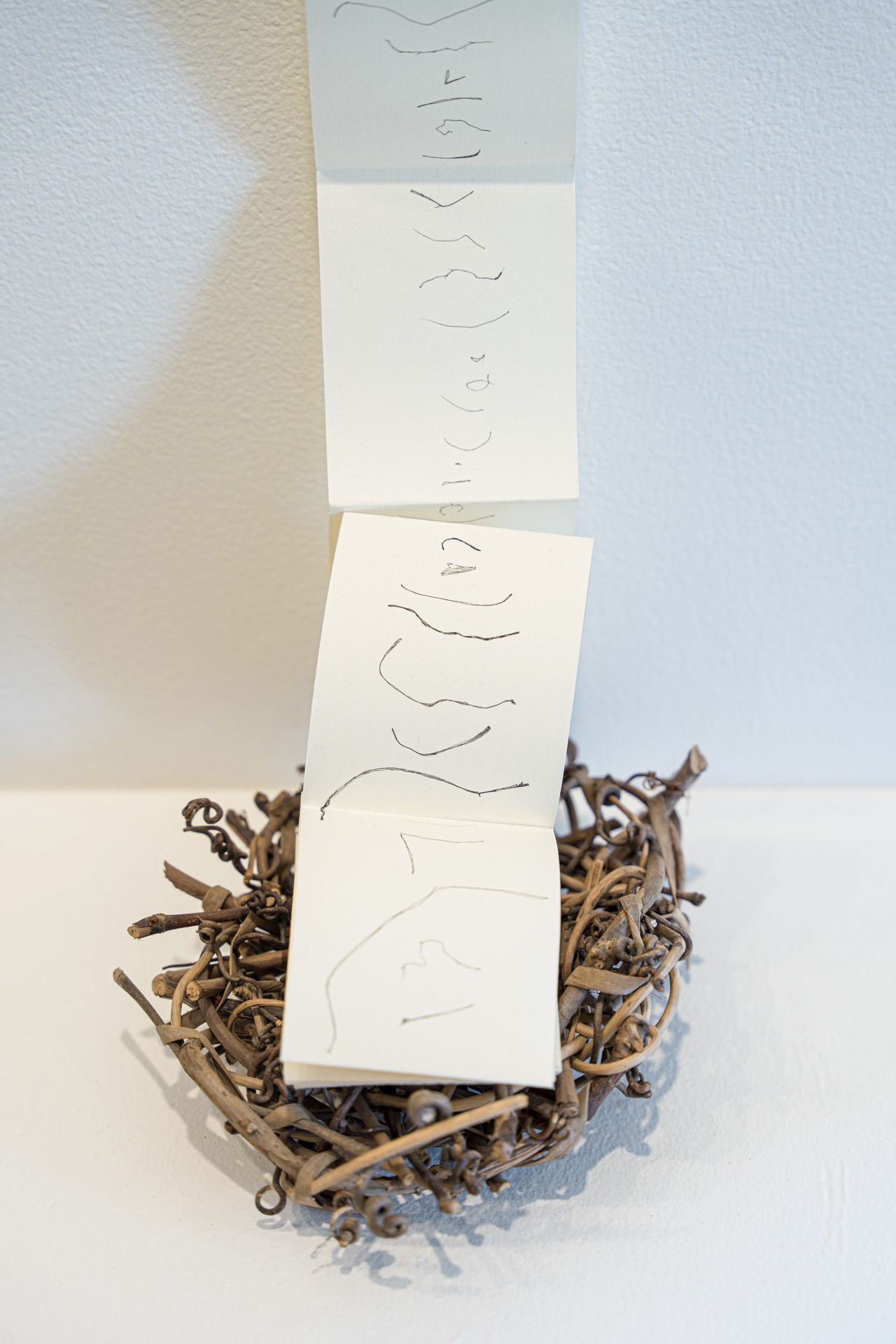

Woven Words

Grapevine (Vitis sp.), black walnut husk dye, honeysuckle vine (Lonicera japonica), pen on rives heavyweight paper

Dimensions variable

By carefully deconstructing entire bird’s nests and drawing each twig and rootlet, I am able to pay tribute to both the bird’s, and my own, diligence and attention to detail. The nest pieces laid out next to each other bear a striking resemblance to the characters of an unreadable, yet incredibly compelling language. In this attempt to understand more-than-human worlds the individual beauty and value of each piece of the nest is highlighted, as well as the whole that they are a part of.

Grapevine (Vitis sp.), black walnut husk dye, honeysuckle vine (Lonicera japonica), pen on rives heavyweight paper

Dimensions variable

By carefully deconstructing entire bird’s nests and drawing each twig and rootlet, I am able to pay tribute to both the bird’s, and my own, diligence and attention to detail. The nest pieces laid out next to each other bear a striking resemblance to the characters of an unreadable, yet incredibly compelling language. In this attempt to understand more-than-human worlds the individual beauty and value of each piece of the nest is highlighted, as well as the whole that they are a part of.

Watershed Topography (Neversink River)

Graphite on paper

9 x 13”

My Watershed Topography series is a group of drawings that present an alternative set of borders for familiar landscapes. Although appearing initially as abstract forms, these dense branching masses actually depict a bird’s eye view of hydrologic structures defined by rainfall and the flow of water across land. In Western earth science, a watershed connotes an area of land that contains a common set of streams and rivers that all drain into a single larger body of water, also sometimes described as a basin or drainage area.

Watershed Topography (Neversink River) depicts the area of land drained by several branches of the Neversink River in the Catskills, and the current footprint of the human-constructed reservoir they drain into, the Neversink Reservoir. The drawing ends at the damn at the southern end of the reservoir. This reservoir and the rivers that flow into it--represented here by the white of the paper surrounded by overland water flows in dark graphite--is one of several reservoirs in the Catskills that catch and hold water from adjacent watersheds that catch and hold water that would otherwise flow southeast into the Delaware River, rerouting it via an aqueduct system to provide drinking water to New York City.

Graphite on paper

9 x 13”

My Watershed Topography series is a group of drawings that present an alternative set of borders for familiar landscapes. Although appearing initially as abstract forms, these dense branching masses actually depict a bird’s eye view of hydrologic structures defined by rainfall and the flow of water across land. In Western earth science, a watershed connotes an area of land that contains a common set of streams and rivers that all drain into a single larger body of water, also sometimes described as a basin or drainage area.

Watershed Topography (Neversink River) depicts the area of land drained by several branches of the Neversink River in the Catskills, and the current footprint of the human-constructed reservoir they drain into, the Neversink Reservoir. The drawing ends at the damn at the southern end of the reservoir. This reservoir and the rivers that flow into it--represented here by the white of the paper surrounded by overland water flows in dark graphite--is one of several reservoirs in the Catskills that catch and hold water from adjacent watersheds that catch and hold water that would otherwise flow southeast into the Delaware River, rerouting it via an aqueduct system to provide drinking water to New York City.

Ghost Estuary (Gowanus Canal)

Graphite on paper

9 x 13”

Ghost Estuary (Gowanus Canal) depicts that past and present footprint of the Gowanus in its transition from a river traversing a marsh into a superfunded canal over several centuries. The darkest gray graphite patches represent the footprint of the Gowanus marshlands circa 1766, the light gray patches represent the flow of the Gowanus Creek at the same time period, while the exposed white paper in the center of the form represents the current canal (see research by Jessica T. Miller).

Graphite on paper

9 x 13”

Ghost Estuary (Gowanus Canal) depicts that past and present footprint of the Gowanus in its transition from a river traversing a marsh into a superfunded canal over several centuries. The darkest gray graphite patches represent the footprint of the Gowanus marshlands circa 1766, the light gray patches represent the flow of the Gowanus Creek at the same time period, while the exposed white paper in the center of the form represents the current canal (see research by Jessica T. Miller).

Watershed Topography: Hudson Headwaters (Calamity Brook/Henderson Lake)

Graphite on paper

12 x 9”

Watershed Topography: Hudson Headwaters (Calamity Brook/Henderson Lake) depicts Calamity Brook, the northernmost tributary of the Hudson River, as it flows past Henderson Lake and joins the Hudson at the Flowed Lands at the northernmost portion of the Hudson/Mahicanituck Watershed in the Adirondacks. The dark graphite patches represent named the creek, lake, river, and marshlands, while the woven branches depict the many complex overland and underground flows that contribute to the watershed.

Graphite on paper

12 x 9”

Watershed Topography: Hudson Headwaters (Calamity Brook/Henderson Lake) depicts Calamity Brook, the northernmost tributary of the Hudson River, as it flows past Henderson Lake and joins the Hudson at the Flowed Lands at the northernmost portion of the Hudson/Mahicanituck Watershed in the Adirondacks. The dark graphite patches represent named the creek, lake, river, and marshlands, while the woven branches depict the many complex overland and underground flows that contribute to the watershed.

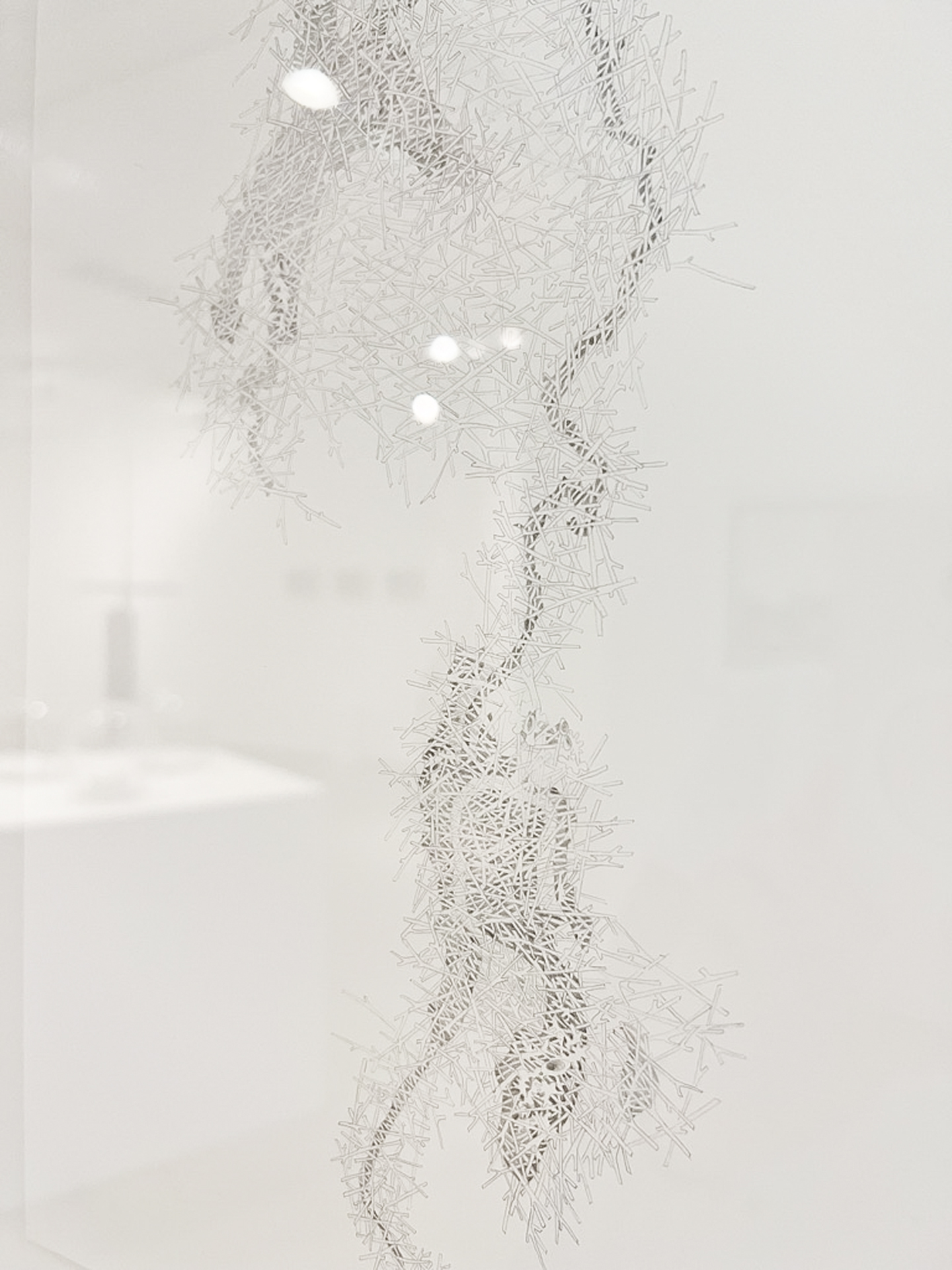

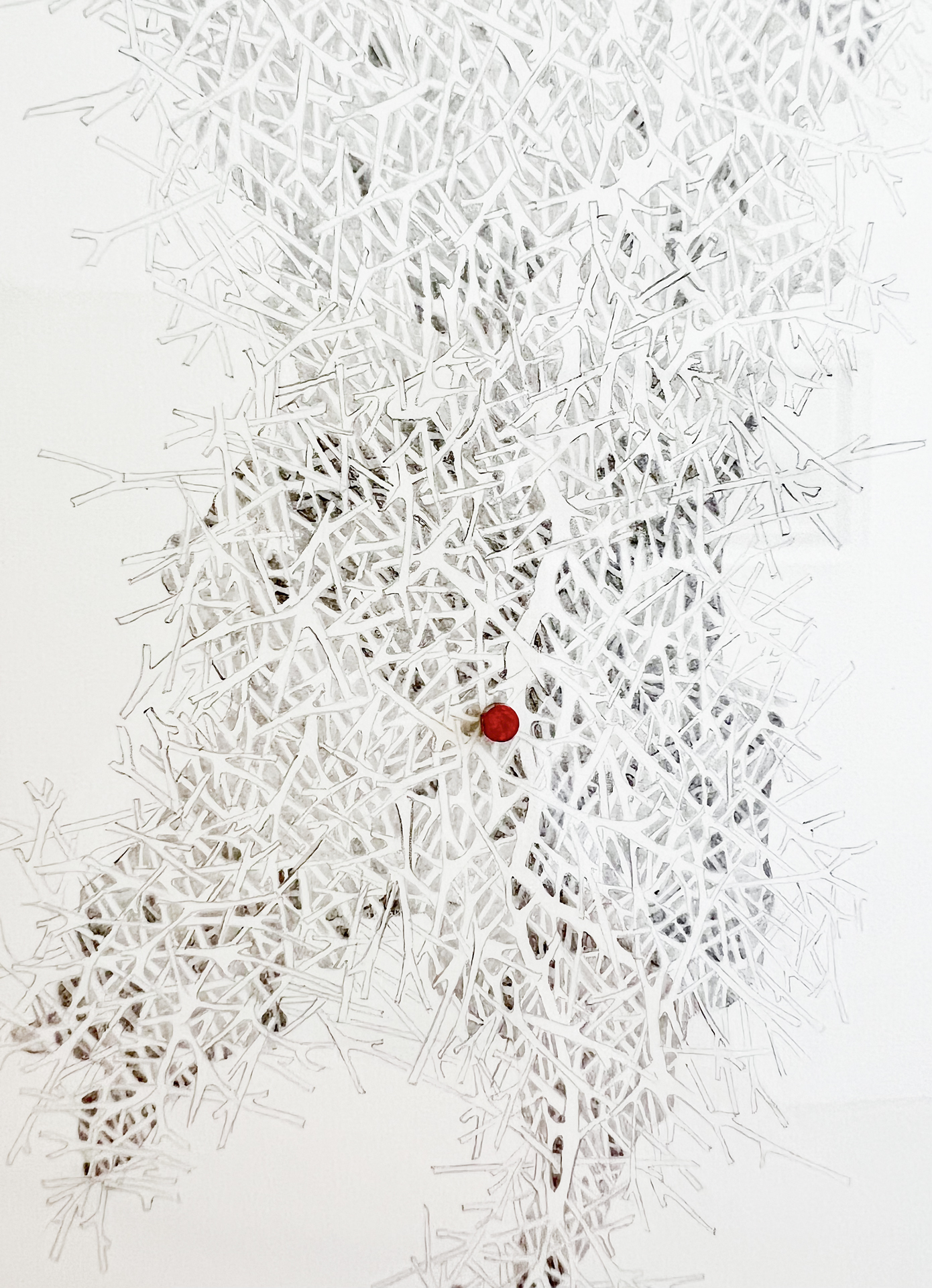

Watershed Topography: You Are Here (Hudson/Mahicanituck)

Graphite on paper, magnets, acrylic paint

11 x 10”

Watershed Topography: You Are Here (Hudson/Mahicanituck) is based on the footprint of the complete Hudson/Mahicanituck Watershed, with a moveable red magnet placed at the location within the watershed where the work is on view. In this drawing, the dark graphite patches represent the land area that makes up the watershed, from the northernmost tip in the Adirondacks, to the southern-most point in New York bay south of Manhattan. The easternmost portion of the watershed is in western New York, drained by the Mohawk River, with the easternmost portion drains parts of current-day Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The branching forms revealing the white of the paper are mostly intuitive representations of the complex, fractal nature of watershed topographies, but some major named rivers are visible, including the Hudson/Mahicanituck running up the watershed’s center, and the Mohawk river coming in from the West and joining the Hudson at current-day Troy, NY.

Graphite on paper, magnets, acrylic paint

11 x 10”

Watershed Topography: You Are Here (Hudson/Mahicanituck) is based on the footprint of the complete Hudson/Mahicanituck Watershed, with a moveable red magnet placed at the location within the watershed where the work is on view. In this drawing, the dark graphite patches represent the land area that makes up the watershed, from the northernmost tip in the Adirondacks, to the southern-most point in New York bay south of Manhattan. The easternmost portion of the watershed is in western New York, drained by the Mohawk River, with the easternmost portion drains parts of current-day Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The branching forms revealing the white of the paper are mostly intuitive representations of the complex, fractal nature of watershed topographies, but some major named rivers are visible, including the Hudson/Mahicanituck running up the watershed’s center, and the Mohawk river coming in from the West and joining the Hudson at current-day Troy, NY.

Watershed Topography: New York Harbor (Past, Present, Future)

Graphite on paper

10 x 8.5”

Watershed Topography: New York Harbor (Past, Present, Future) is based on maps of past, current, and future water levels where the Hudson river passes through current-day New York City and empties into the Atlantic at New York Bay. The dark gray graphite patches represent portions of the river’s mouth that are water currently, in the 21st Century, including the Hudson, East River, Jamaica Bay, New York Harbor, New York Bay, and a small portion of the Atlantic Ocean in the southeastern corner of the frame. The light gray patches are an amalgamation of past river and tidal topographies from the pre and early colonial period, before the river was dredged and its edges filled and hardened, along with influences from projected maps of sea level rise and coastal flooding over the next 100 years. The white were dry land prior to colonization, and are predicted to remain dry land over the next century (see research by Jessica Cox, George Colbert, and Guenter Vollath and FEMA’s flood maps).

Graphite on paper

10 x 8.5”

Watershed Topography: New York Harbor (Past, Present, Future) is based on maps of past, current, and future water levels where the Hudson river passes through current-day New York City and empties into the Atlantic at New York Bay. The dark gray graphite patches represent portions of the river’s mouth that are water currently, in the 21st Century, including the Hudson, East River, Jamaica Bay, New York Harbor, New York Bay, and a small portion of the Atlantic Ocean in the southeastern corner of the frame. The light gray patches are an amalgamation of past river and tidal topographies from the pre and early colonial period, before the river was dredged and its edges filled and hardened, along with influences from projected maps of sea level rise and coastal flooding over the next 100 years. The white were dry land prior to colonization, and are predicted to remain dry land over the next century (see research by Jessica Cox, George Colbert, and Guenter Vollath and FEMA’s flood maps).

Branded

Container 4 x 6 x 6"

Patent number laser-etched into Roundup-ready corn kernels.

Container 4 x 6 x 6"

Patent number laser-etched into Roundup-ready corn kernels.

Spectacles

Vintage optical instruments, utensils, brass, with gold-leafed radish and beets, soil, and radish and beet seeds, plates, and bell jars

7 x 3 x 4"

Borrowing the visual language from early natural science instruments, this series of dining implements alludes to the time when Western scientific inquiry relied on the inspection of natural specimens. These art pieces enable participants to step back in time and re-discover that sense of wonder, while playfully examining the micro and macro aspects of their food. Each grouping of objects in the series is based on a specific type of apparatus: antique opera binoculars, map readers, telescope/microscope barrels, proportional drafting, and navigational chart dividers. Each antique piece is reassembled and retrofitted with other found and hand-fabricated elements to create an individually unique piece.

Vintage optical instruments, utensils, brass, with gold-leafed radish and beets, soil, and radish and beet seeds, plates, and bell jars

7 x 3 x 4"

Borrowing the visual language from early natural science instruments, this series of dining implements alludes to the time when Western scientific inquiry relied on the inspection of natural specimens. These art pieces enable participants to step back in time and re-discover that sense of wonder, while playfully examining the micro and macro aspects of their food. Each grouping of objects in the series is based on a specific type of apparatus: antique opera binoculars, map readers, telescope/microscope barrels, proportional drafting, and navigational chart dividers. Each antique piece is reassembled and retrofitted with other found and hand-fabricated elements to create an individually unique piece.

Furrow Seed Stories

Hand-engraved seeds

Each container approx 4 x 6 x 6"

Seeds are fundamental units in our relationship with food, agriculture, and the natural environment. On both physical and symbolic levels, seeds collectively carry the history of complex motives and consequences of plant domestication. Seeds have been both silent witnesses and active participants in waves of travels and migrations, growth and decline, and individual and societal transformations. Seeds are also records of more personal stories of people or families that cultivated them for generations. Such diversity and richness in the deeply rooted relationships of people and seeds remain mostly silent, physically, and figuratively locked inside the coat of each seed. By traveling the country and connecting with a multitude of people and organizations that contribute to seed advocacy, the Furrow project seeks to make those often-compelling stories visible, to externalize and memorialize the contributions of professional and enthusiast growers, breeders, and seed-savers. The nature of the artist's hand guiding a cutting tool and creating a miniature furrow in a shell of a seed alludes to a farmer's plow piercing through the top layer of soil, releasing nutrients and jump-starting a cycle of growth. The symbolic act of piercing through the seed coat to uncover the information contained within is coupled with the physical function of helping it germinate if planted. The motifs are based on stories relevant to the nature of specific seeds and the people or organizations who provide them.

Descriptions of the seeds in containers (left to right):

1. American Chestnut, Illustrating the various methods for breeding a blight-resistant Castanea Dentata tree species, engraved on chestnuts

2. Antique Atlas, made for True-Love Seeds company, on Fava bean

3. Hudson Valley Farms, seed motifs; Clockwise from top:

Mill-stone movements, for Wild Hive Farm on Adlay's millet seed.

Logotype, for Phillies Bridge Farm Project on Blue Hopi maize kernel.

Three Sisters, for Native American Seed Sanctuary at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub on Red Maize kernel. Logotype, for Rondout Valley Growers Association on Hank's X-tra Special Baking bean.

Life-forces, for Long Season Farm on Otto File Flint maize kernel.

Memory, for Maynard Orchard on Macoun Apple seed.

Center: Tome, for Hudson Valley Seed Company on Butternut Squash seed.

4. Watershed, private commission, on Pawpaw seed.

5. Farming Soils of the Rondout Valley, Silt-loam soil horizons/strata on tiger beans.

Hand-engraved seeds

Each container approx 4 x 6 x 6"

Seeds are fundamental units in our relationship with food, agriculture, and the natural environment. On both physical and symbolic levels, seeds collectively carry the history of complex motives and consequences of plant domestication. Seeds have been both silent witnesses and active participants in waves of travels and migrations, growth and decline, and individual and societal transformations. Seeds are also records of more personal stories of people or families that cultivated them for generations. Such diversity and richness in the deeply rooted relationships of people and seeds remain mostly silent, physically, and figuratively locked inside the coat of each seed. By traveling the country and connecting with a multitude of people and organizations that contribute to seed advocacy, the Furrow project seeks to make those often-compelling stories visible, to externalize and memorialize the contributions of professional and enthusiast growers, breeders, and seed-savers. The nature of the artist's hand guiding a cutting tool and creating a miniature furrow in a shell of a seed alludes to a farmer's plow piercing through the top layer of soil, releasing nutrients and jump-starting a cycle of growth. The symbolic act of piercing through the seed coat to uncover the information contained within is coupled with the physical function of helping it germinate if planted. The motifs are based on stories relevant to the nature of specific seeds and the people or organizations who provide them.

Descriptions of the seeds in containers (left to right):

1. American Chestnut, Illustrating the various methods for breeding a blight-resistant Castanea Dentata tree species, engraved on chestnuts

2. Antique Atlas, made for True-Love Seeds company, on Fava bean

3. Hudson Valley Farms, seed motifs; Clockwise from top:

Mill-stone movements, for Wild Hive Farm on Adlay's millet seed.

Logotype, for Phillies Bridge Farm Project on Blue Hopi maize kernel.

Three Sisters, for Native American Seed Sanctuary at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub on Red Maize kernel. Logotype, for Rondout Valley Growers Association on Hank's X-tra Special Baking bean.

Life-forces, for Long Season Farm on Otto File Flint maize kernel.

Memory, for Maynard Orchard on Macoun Apple seed.

Center: Tome, for Hudson Valley Seed Company on Butternut Squash seed.

4. Watershed, private commission, on Pawpaw seed.

5. Farming Soils of the Rondout Valley, Silt-loam soil horizons/strata on tiger beans.

Kite and Robbie Wing

http://kitekitekitekite.com/

@kitekitekitekitekite

http://robbiewing.com/

@wingrobbie

Owákhitȟaŋiŋ

8-channel sound installation

12 minutes and 16 seconds

Field recordings taken at dusk and dawn in the Stover Tióšpaye, near No Flesh Creek and Kyle Dam in Kyle, South Dakota.

8-channel sound installation

12 minutes and 16 seconds

Field recordings taken at dusk and dawn in the Stover Tióšpaye, near No Flesh Creek and Kyle Dam in Kyle, South Dakota.

Nuŋȟwáuŋzazapi (We Only Hear Snatches of What is Said)

Framed photograph

3 x 4'

Image of taking field recordings taken at dusk and dawn in the Stover Tióšpaye, near No Flesh Creek and Kyle Dam in Kyle, South Dakota.

Framed photograph

3 x 4'

Image of taking field recordings taken at dusk and dawn in the Stover Tióšpaye, near No Flesh Creek and Kyle Dam in Kyle, South Dakota.

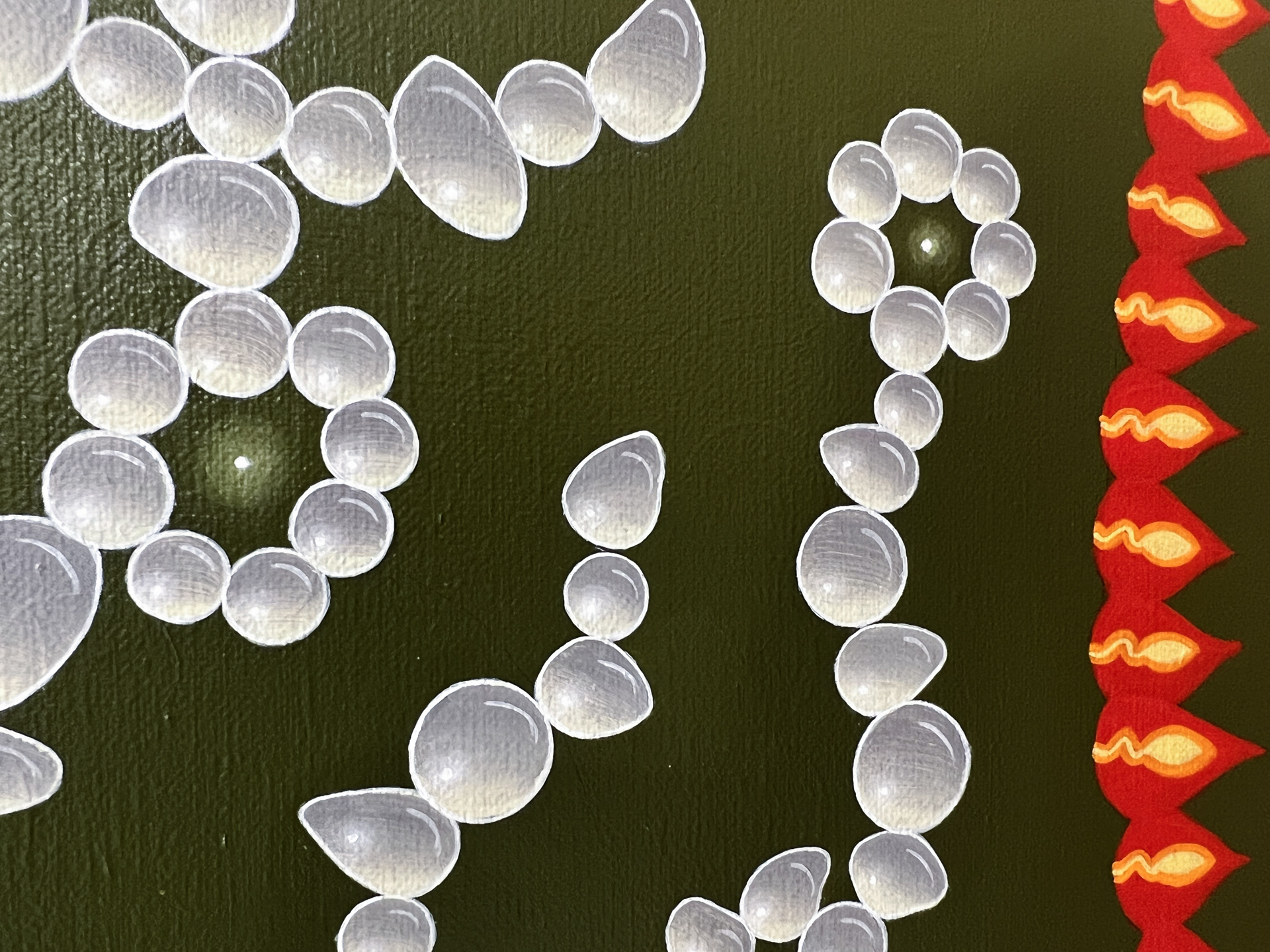

Knot of Flows 1 and Knot of Flows 2

Acrylic on linen

26 x 21 x 1”

Knot of Flows is a metaphor image that challenges our relationship with time. Shaped as a thread of little rocks with the background color palette of the Hudson River, the knot of flows is portrayed to be a prayer on a body of water, to affirm our interconnectedness with the landscape that goes beyond rationality and cartesian frameworks of existence.

26 x 21 x 1”

Knot of Flows is a metaphor image that challenges our relationship with time. Shaped as a thread of little rocks with the background color palette of the Hudson River, the knot of flows is portrayed to be a prayer on a body of water, to affirm our interconnectedness with the landscape that goes beyond rationality and cartesian frameworks of existence.

34.45553,-103.0077549 and 34.233707,-103.084940

Acrylic on canvas, embroidery thread on canvas

26 x 39”

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 39”

Finding aesthetic value in utilitarian forms, the Transitional Spaces series takes its inspiration from the landscape and Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains region of the United States where groundwater pivot irrigation is widely used to support industrial agriculture. Referencing satellite imagery, circles from irrigation, squares delineated by roadways, and the repeated linear elements of plowed fields are drawn upon for inherent colors, forms, patterns, and textures. These repeated geometric forms cover thousands of square miles. When flying over this region, the marks of human intervention are on stark view and can be seen and experienced in ways not noticeable from the ground. The sheer scale is awe inspiring and unsettling. Through the process of groundwater pivot irrigation, the extractive demands of industrial agriculture are draining the Ogallala Aquifer far more quickly than it can be naturally replenished. This interdisciplinary body of work explores the paradox of technological optimism within the framework of 21st century capitalist production in relation to the food supply we’re all dependent on.

Water is a key element in the acrylic paintings on canvas, as thin watery layers of pigment are applied to build up the surface in each work. In addition to the painting process, hand embroidery is also incorporated into two of the works on canvas. The embroidery thread is created by unraveling sheets of canvas, allowing the painting’s support to play an important aesthetic and metaphorical role, as the underlying material is literally consumed for the works creation, paralleling the processes of extractive groundwater irrigation. Through the unseen and meticulous process of unraveling canvas, collecting numerous threads, then hand-stitching linear embroidery patterns to reference the linear patterns created through plowing, planting, and harvesting crops, my artistic labor also stands in solidarity with workers doing difficult physical and unseen labor.

Acrylic on canvas, embroidery thread on canvas

26 x 39”

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 39”

Finding aesthetic value in utilitarian forms, the Transitional Spaces series takes its inspiration from the landscape and Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains region of the United States where groundwater pivot irrigation is widely used to support industrial agriculture. Referencing satellite imagery, circles from irrigation, squares delineated by roadways, and the repeated linear elements of plowed fields are drawn upon for inherent colors, forms, patterns, and textures. These repeated geometric forms cover thousands of square miles. When flying over this region, the marks of human intervention are on stark view and can be seen and experienced in ways not noticeable from the ground. The sheer scale is awe inspiring and unsettling. Through the process of groundwater pivot irrigation, the extractive demands of industrial agriculture are draining the Ogallala Aquifer far more quickly than it can be naturally replenished. This interdisciplinary body of work explores the paradox of technological optimism within the framework of 21st century capitalist production in relation to the food supply we’re all dependent on.

Water is a key element in the acrylic paintings on canvas, as thin watery layers of pigment are applied to build up the surface in each work. In addition to the painting process, hand embroidery is also incorporated into two of the works on canvas. The embroidery thread is created by unraveling sheets of canvas, allowing the painting’s support to play an important aesthetic and metaphorical role, as the underlying material is literally consumed for the works creation, paralleling the processes of extractive groundwater irrigation. Through the unseen and meticulous process of unraveling canvas, collecting numerous threads, then hand-stitching linear embroidery patterns to reference the linear patterns created through plowing, planting, and harvesting crops, my artistic labor also stands in solidarity with workers doing difficult physical and unseen labor.

34.200845,-103.156917

Acrylic on canvas, embroidery thread on canvas

34 x 45”

Finding aesthetic value in utilitarian forms, the Transitional Spaces series takes its inspiration from the landscape and Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains region of the United States where groundwater pivot irrigation is widely used to support industrial agriculture. Referencing satellite imagery, circles from irrigation, squares delineated by roadways, and the repeated linear elements of plowed fields are drawn upon for inherent colors, forms, patterns, and textures. These repeated geometric forms cover thousands of square miles. When flying over this region, the marks of human intervention are on stark view and can be seen and experienced in ways not noticeable from the ground. The sheer scale is awe inspiring and unsettling. Through the process of groundwater pivot irrigation, the extractive demands of industrial agriculture are draining the Ogallala Aquifer far more quickly than it can be naturally replenished. This interdisciplinary body of work explores the paradox of technological optimism within the framework of 21st century capitalist production in relation to the food supply we’re all dependent on.

Water is a key element in the acrylic paintings on canvas, as thin watery layers of pigment are applied to build up the surface in each work. In addition to the painting process, hand embroidery is also incorporated into two of the works on canvas. The embroidery thread is created by unraveling sheets of canvas, allowing the painting’s support to play an important aesthetic and metaphorical role, as the underlying material is literally consumed for the works creation, paralleling the processes of extractive groundwater irrigation. Through the unseen and meticulous process of unraveling canvas, collecting numerous threads, then hand-stitching linear embroidery patterns to reference the linear patterns created through plowing, planting, and harvesting crops, my artistic labor also stands in solidarity with workers doing difficult physical and unseen labor.

Acrylic on canvas, embroidery thread on canvas

34 x 45”

Finding aesthetic value in utilitarian forms, the Transitional Spaces series takes its inspiration from the landscape and Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains region of the United States where groundwater pivot irrigation is widely used to support industrial agriculture. Referencing satellite imagery, circles from irrigation, squares delineated by roadways, and the repeated linear elements of plowed fields are drawn upon for inherent colors, forms, patterns, and textures. These repeated geometric forms cover thousands of square miles. When flying over this region, the marks of human intervention are on stark view and can be seen and experienced in ways not noticeable from the ground. The sheer scale is awe inspiring and unsettling. Through the process of groundwater pivot irrigation, the extractive demands of industrial agriculture are draining the Ogallala Aquifer far more quickly than it can be naturally replenished. This interdisciplinary body of work explores the paradox of technological optimism within the framework of 21st century capitalist production in relation to the food supply we’re all dependent on.

Water is a key element in the acrylic paintings on canvas, as thin watery layers of pigment are applied to build up the surface in each work. In addition to the painting process, hand embroidery is also incorporated into two of the works on canvas. The embroidery thread is created by unraveling sheets of canvas, allowing the painting’s support to play an important aesthetic and metaphorical role, as the underlying material is literally consumed for the works creation, paralleling the processes of extractive groundwater irrigation. Through the unseen and meticulous process of unraveling canvas, collecting numerous threads, then hand-stitching linear embroidery patterns to reference the linear patterns created through plowing, planting, and harvesting crops, my artistic labor also stands in solidarity with workers doing difficult physical and unseen labor.

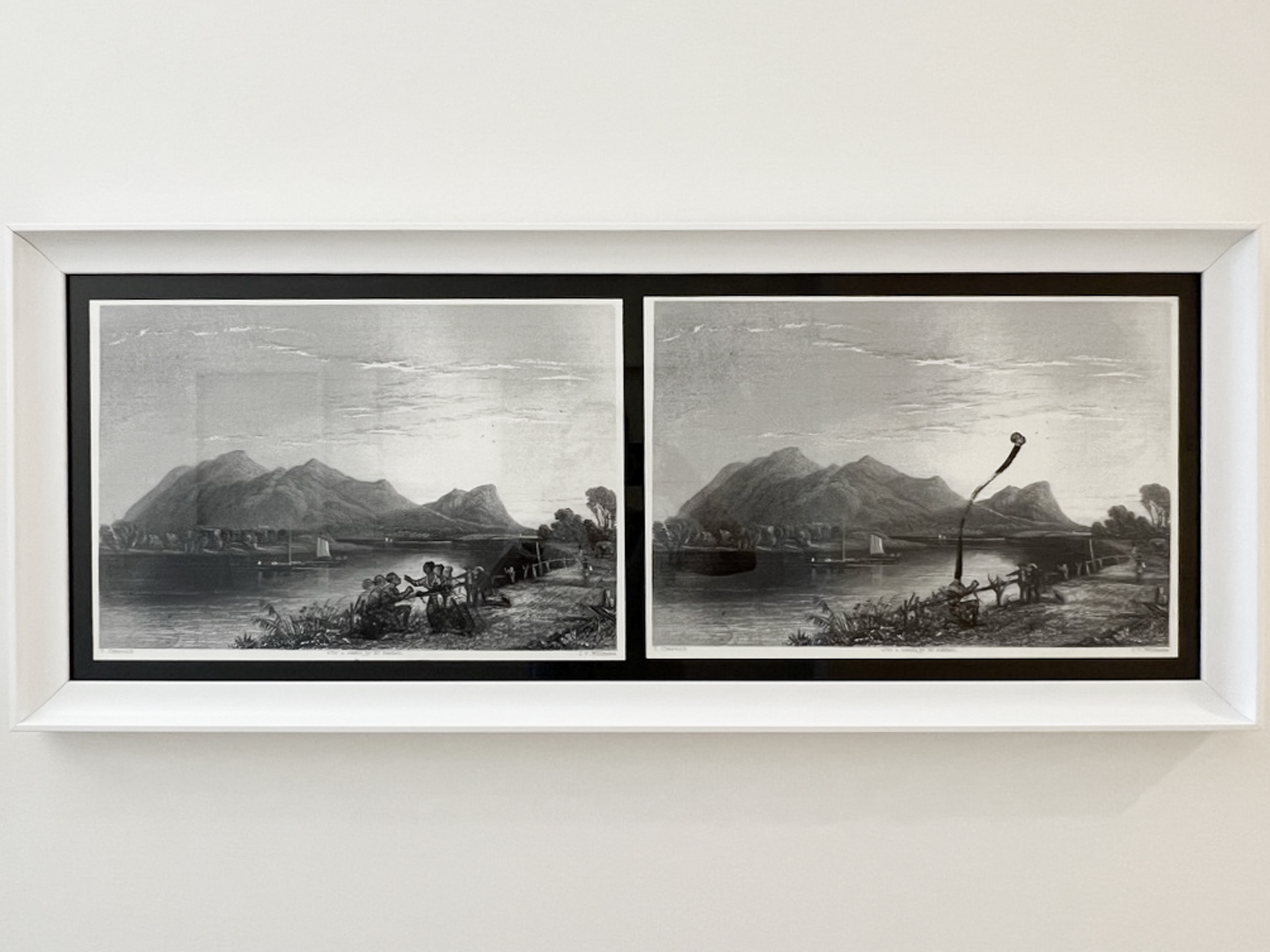

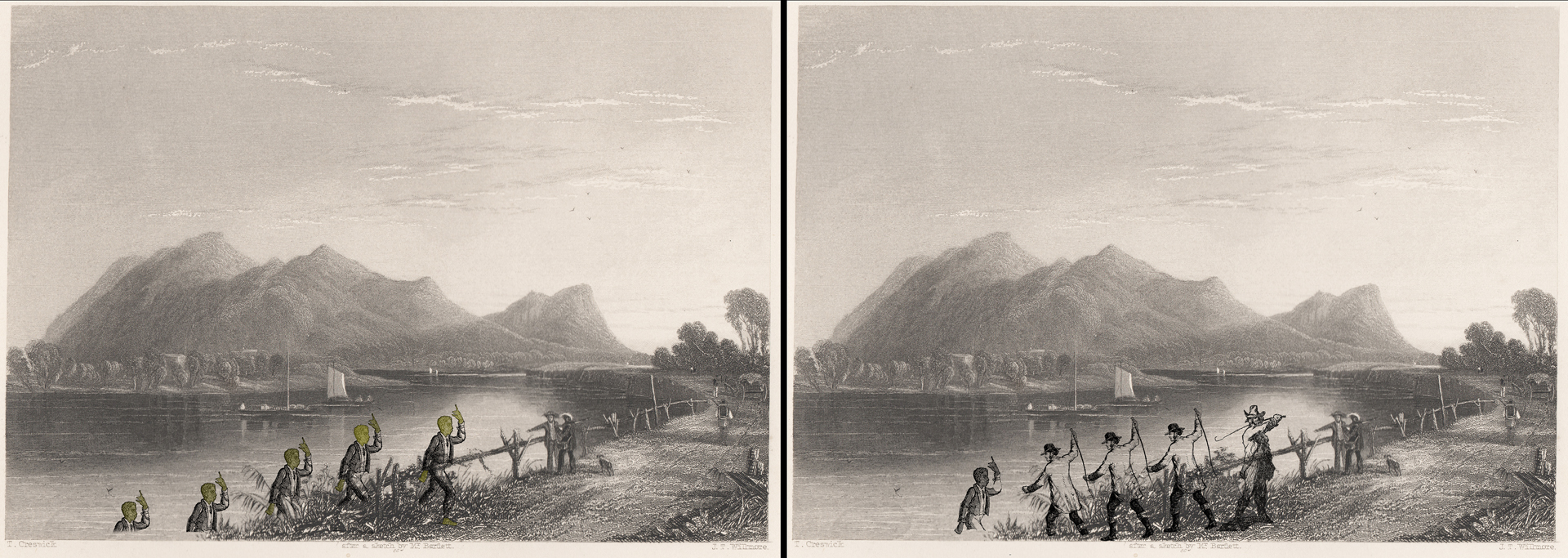

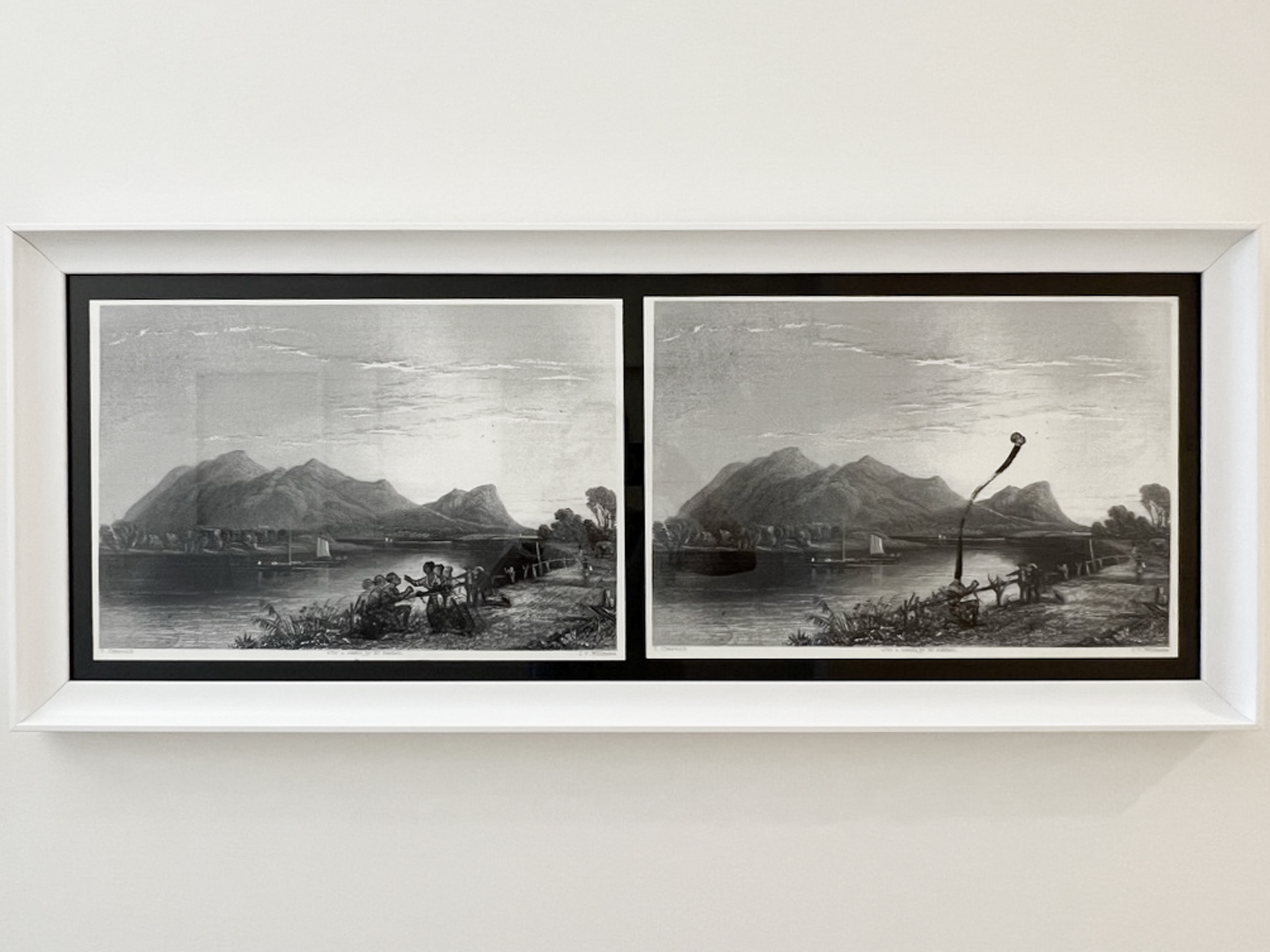

Blood of Souls, Diadem of Kings and Love is a Form of Death

Monoprint on archival inkjet print

Since 2019 I’ve been collecting original 19th century landscape engravings typical of the representational idealism of the Hudson River School and altering them to include images of captured fugitive slaves and Underground Railroad caravans from anti- slavery tracts and illustrated abolitionist literature which are very close in historical contemporaneity to the original printed engravings. As an artist of mixed-race working in the Hudson Valley, my “a-Historical Landscapes” are a decolonizing strategy to interrogate art historical conventions and aim to serve as a corrective by filling the absences left by those dominant narratives.

Monoprint on archival inkjet print

Since 2019 I’ve been collecting original 19th century landscape engravings typical of the representational idealism of the Hudson River School and altering them to include images of captured fugitive slaves and Underground Railroad caravans from anti- slavery tracts and illustrated abolitionist literature which are very close in historical contemporaneity to the original printed engravings. As an artist of mixed-race working in the Hudson Valley, my “a-Historical Landscapes” are a decolonizing strategy to interrogate art historical conventions and aim to serve as a corrective by filling the absences left by those dominant narratives.

Wind Drawing #2 and Wind Drawing #12

Charcoal powder, Arches paper

12 x 15” framed

26 x 34 x 2” framed

The consistent theme of my work has been marking time through observable changes in natural phenomena. Invisible wind is seen only through its effects on other elements, in trees, for example. In this work, after stamping Arches paper with charcoal powder (made from charred wood), and allowing the wind to activate the powder, we see the wind’s movement across the paper and that movement is fixed in time. I note the speed and direction in graphite.

Charcoal powder, Arches paper

12 x 15” framed

26 x 34 x 2” framed

The consistent theme of my work has been marking time through observable changes in natural phenomena. Invisible wind is seen only through its effects on other elements, in trees, for example. In this work, after stamping Arches paper with charcoal powder (made from charred wood), and allowing the wind to activate the powder, we see the wind’s movement across the paper and that movement is fixed in time. I note the speed and direction in graphite.

Time Story #13

Wood, paint, graphite, basalt stone from Hudson Valley

28 x 28 x 1”

The Time Story Series creates a map of potential observances of natural phenomena. The sculpture (of wood, paint, graphite, and local basalt stone), invites stories of deep-time stone, and shadows, along with wood and its tree-grain timelines. Anything that rests ephemerally on its surface is participant: for example, sunlight, leaves and wind, insects, etc. The first shadow is drawn (as graphite dashes) and invites a layering of new shadows to come. With artist as recorder, photographs are a complementary component to this work.

Wood, paint, graphite, basalt stone from Hudson Valley

28 x 28 x 1”

The Time Story Series creates a map of potential observances of natural phenomena. The sculpture (of wood, paint, graphite, and local basalt stone), invites stories of deep-time stone, and shadows, along with wood and its tree-grain timelines. Anything that rests ephemerally on its surface is participant: for example, sunlight, leaves and wind, insects, etc. The first shadow is drawn (as graphite dashes) and invites a layering of new shadows to come. With artist as recorder, photographs are a complementary component to this work.

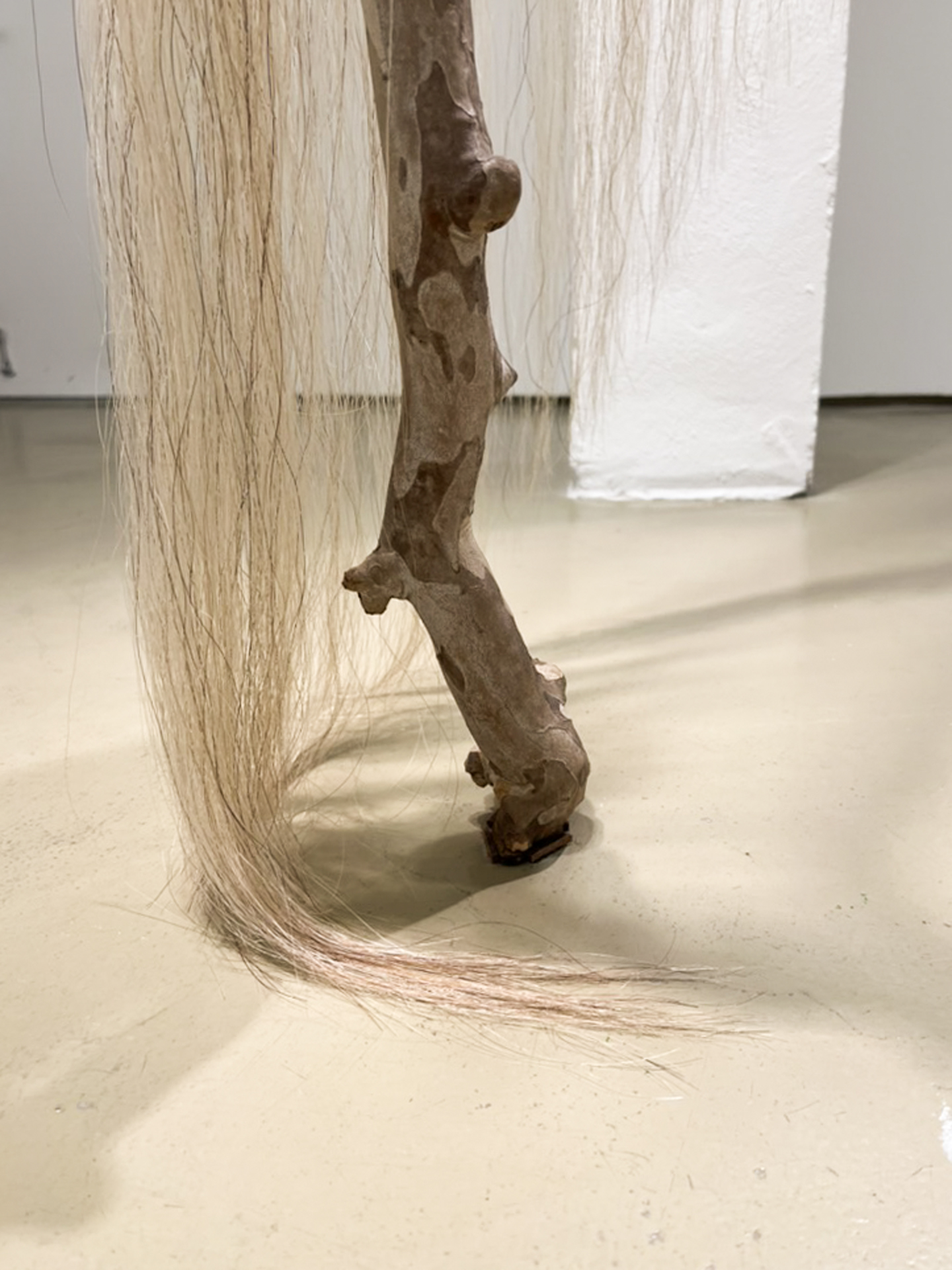

Liminal

Grapevine, sycamore, horse hair, thread

94 x 15 x 39”

Liminal is a threshold made from the once living bodies of plants and animals and the inert Cartesian planes of the built architecture we inhabit. The curvilinear line though organic is nevertheless constructed using simple joining techniques as is the scrim of hair. Liminal is a visual poem about portals belonging to a series of works Known/Not Known made during the time of my father’s passage from the living world.

Grapevine, sycamore, horse hair, thread

94 x 15 x 39”

Liminal is a threshold made from the once living bodies of plants and animals and the inert Cartesian planes of the built architecture we inhabit. The curvilinear line though organic is nevertheless constructed using simple joining techniques as is the scrim of hair. Liminal is a visual poem about portals belonging to a series of works Known/Not Known made during the time of my father’s passage from the living world.

This Was My Home, My Body, My Voice

Wood, barbed wire, fur, roots, pencil, pigments

Height variable to 128 x 67 x 6”

The writing and counting marks that occur in the horizontal shadows of the barbed wire and within the ascending drawn line are of a language no longer known. The narrative continues to exist however. Drawn directly onto the wall, the current place and moment are implicated. The question of whose home/body/voice is underlined by the fur and roots tangled in the barbed wire, their textures barely distinguishable from the pencil marks and shadows. As I make the marks on the wall, I am a conduit for memory of stories of loss.

Wood, barbed wire, fur, roots, pencil, pigments

Height variable to 128 x 67 x 6”

The writing and counting marks that occur in the horizontal shadows of the barbed wire and within the ascending drawn line are of a language no longer known. The narrative continues to exist however. Drawn directly onto the wall, the current place and moment are implicated. The question of whose home/body/voice is underlined by the fur and roots tangled in the barbed wire, their textures barely distinguishable from the pencil marks and shadows. As I make the marks on the wall, I am a conduit for memory of stories of loss.

Three

Grapevine, horse hair

(Dimensions variable) Installation 125 x 140 x 84”

These three forms belong to a larger series When There Were Birds, an installation that has had as many as 13 suspended hair and vine forms in various iterations and performances since 2019. The work originated in response to the 2019 reporting of 3 billion birds - 29% of the population – vanished from North America since 1970.

Grapevine, horse hair

(Dimensions variable) Installation 125 x 140 x 84”

These three forms belong to a larger series When There Were Birds, an installation that has had as many as 13 suspended hair and vine forms in various iterations and performances since 2019. The work originated in response to the 2019 reporting of 3 billion birds - 29% of the population – vanished from North America since 1970.

Press for Listening to Land

Warwick Advertiser, 13 June 2023

Upstate Art Weekend Journeys (Featured in ‘Route 4)

Highlands Current July 14 2023 (Donna Francis’ Mercy is featured)

Receptions & Gallery Talks

Ann Street Gallery wishes to thank our generous supporters for sharing their time and talents during our summer exhibition:

Exhibition support: Travis Schaben

Reception Documentation: Adam DuVuyst

Gallery Attendants: Alba Borchert, Erica Hauser, Pam LaLonde, Nancy Layne, Odessa Patmos, Anna Penny, Denean Ritchie, Jackie Skrzynski

Listening to Land is generously supported, in part, by: