RESOURCES

The Archaeology, Osteology, and History of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground By

Derrick J. Marcucci, RPA

Kenneth Nystrom, Ph.D.

Christina A. Ziegler-McPherson, Ph.D.

Jessica Schreyer

Susan Gade, RPA

Excerpts:

- Historic Context (Dr. Christina Ziegler McPherson)

-

Burial Descriptions (Landmark Archeology, Inc)

-

Burial Photos

-

Archaeological Research Issues Discussion (Landmark Archeology, Inc)

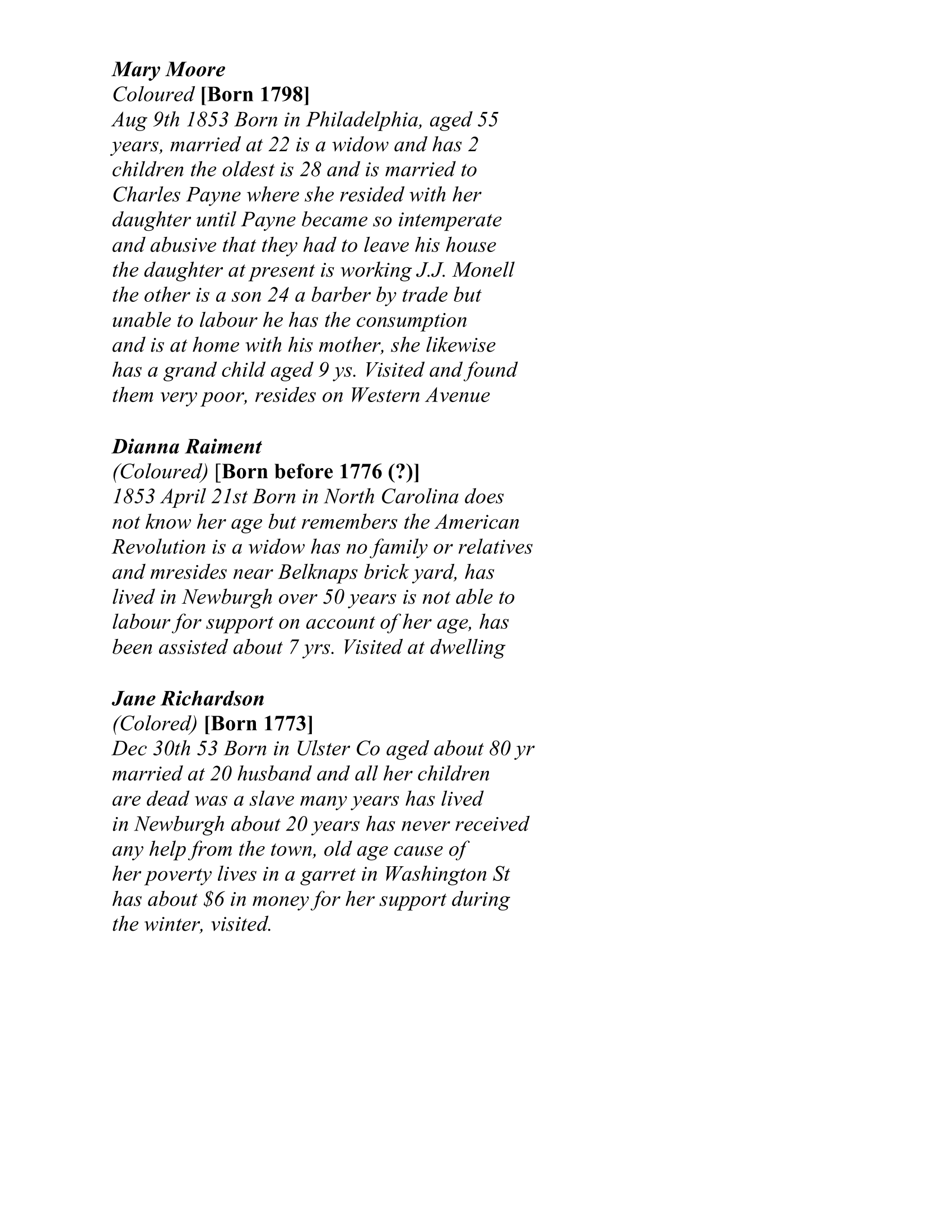

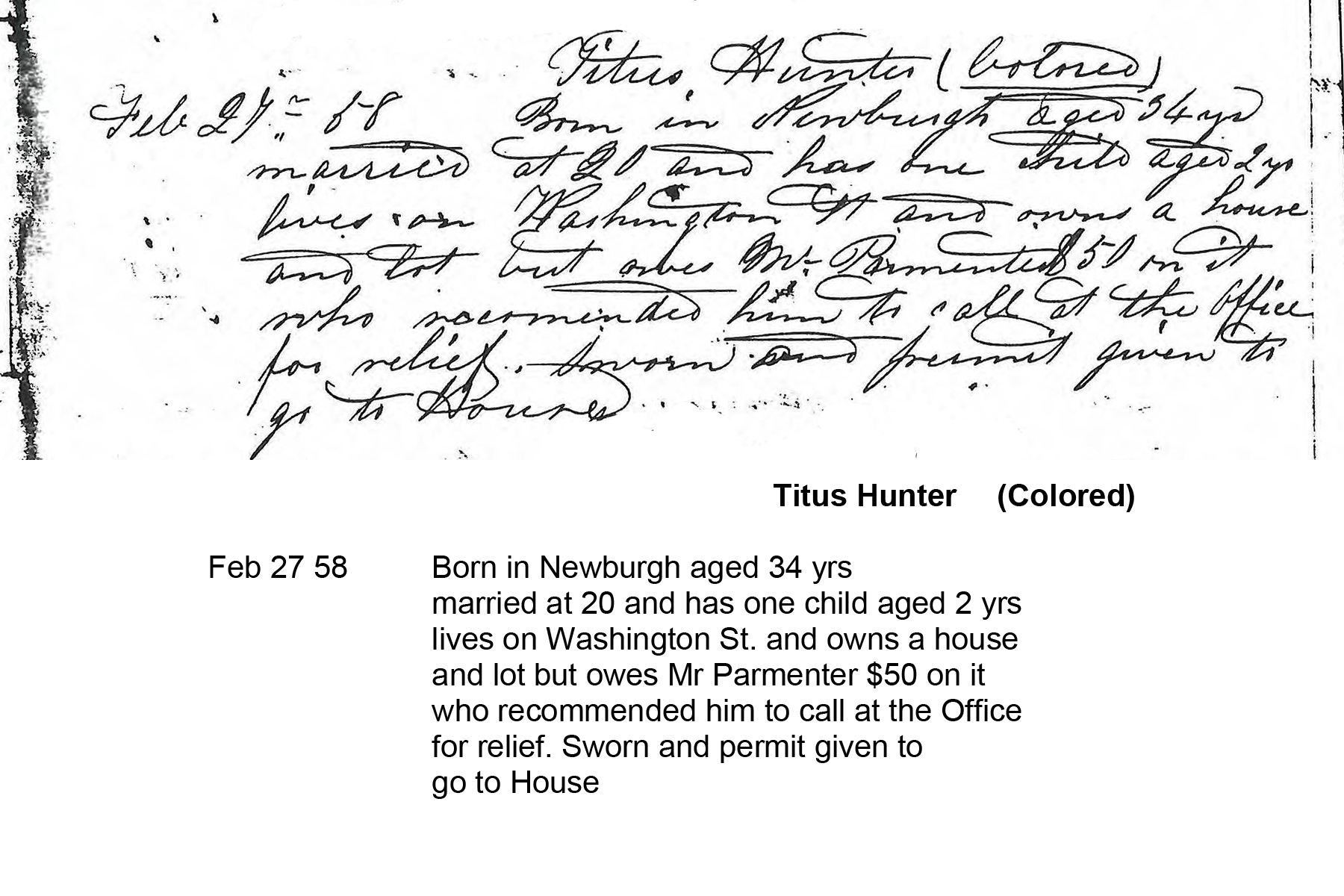

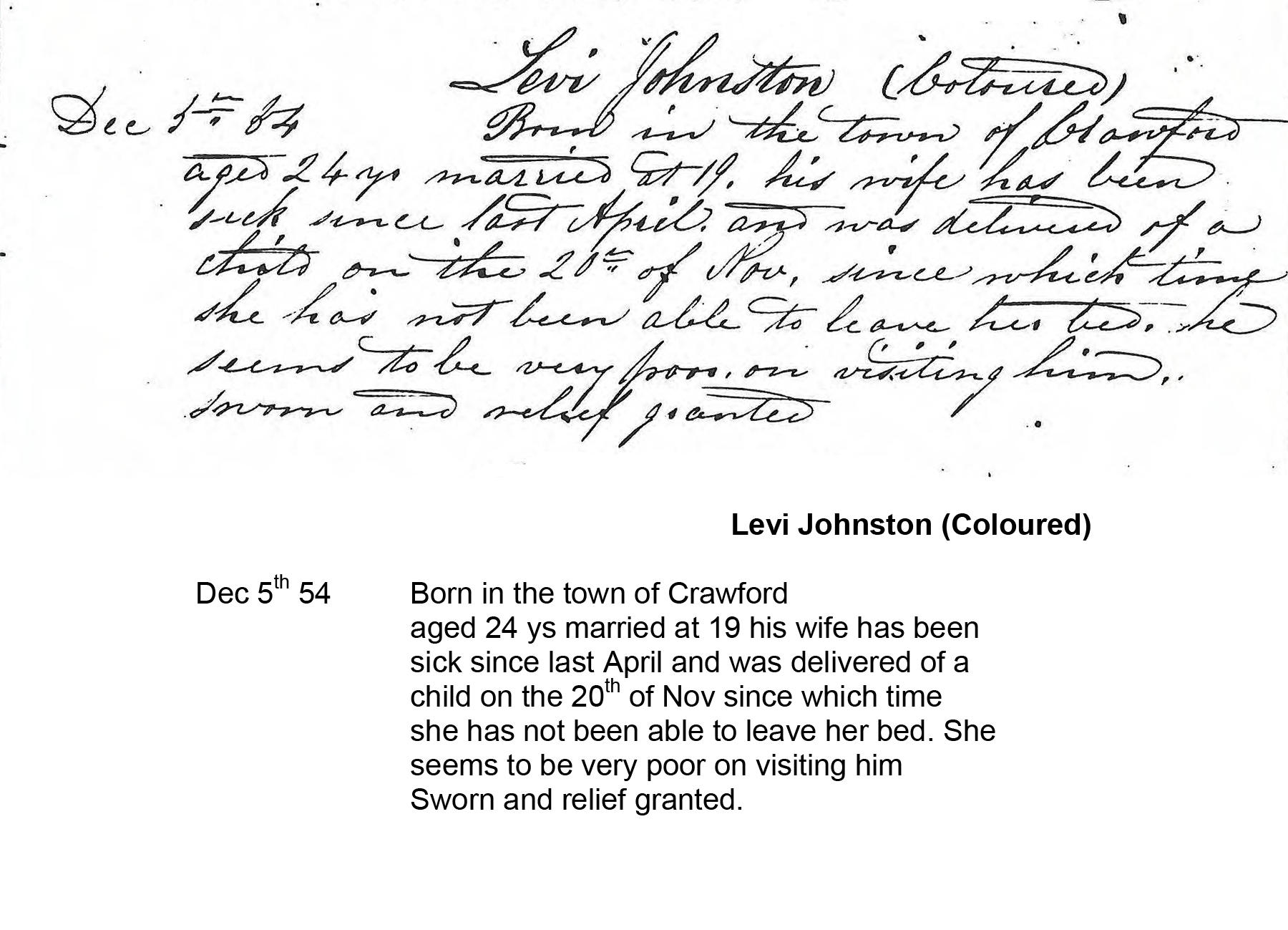

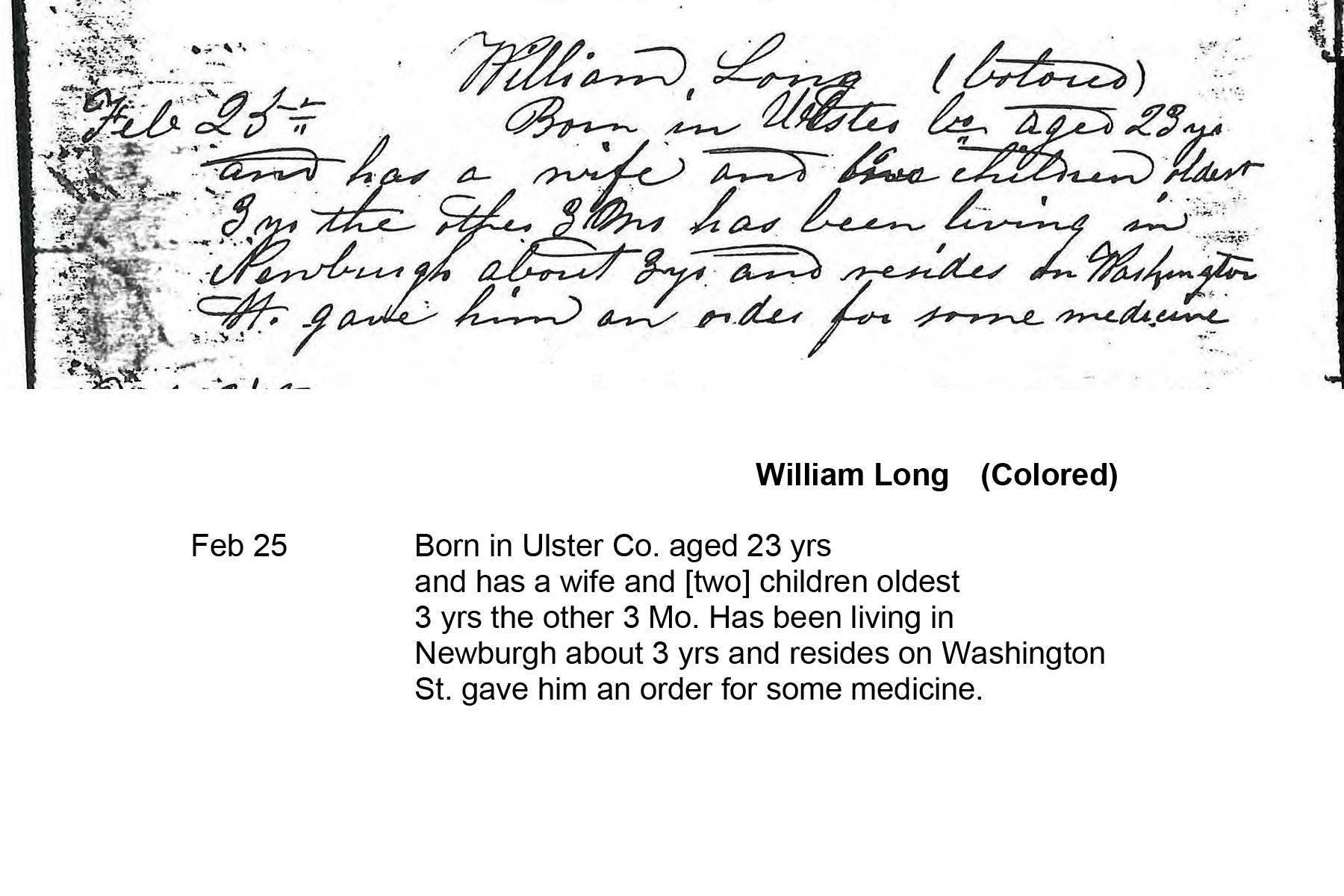

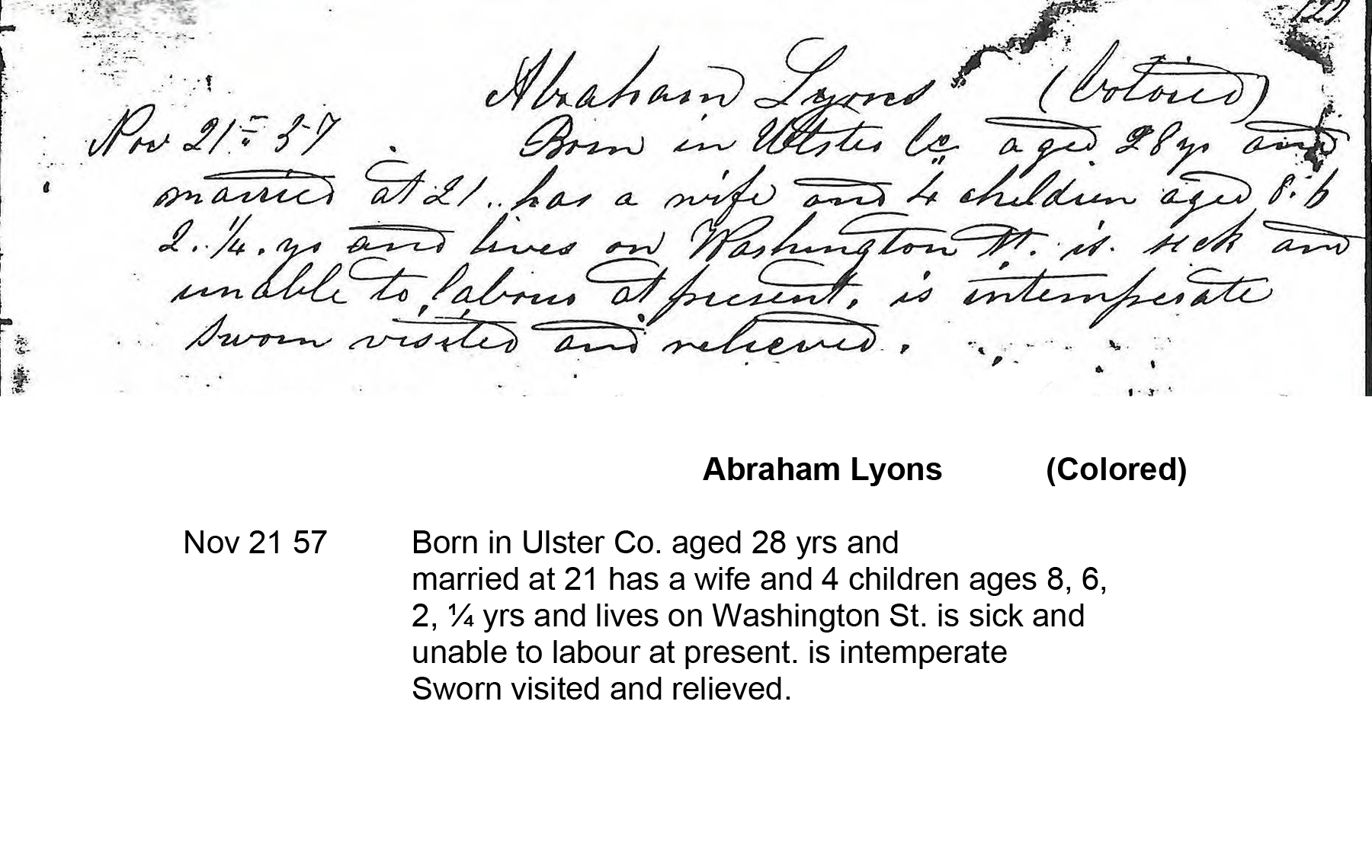

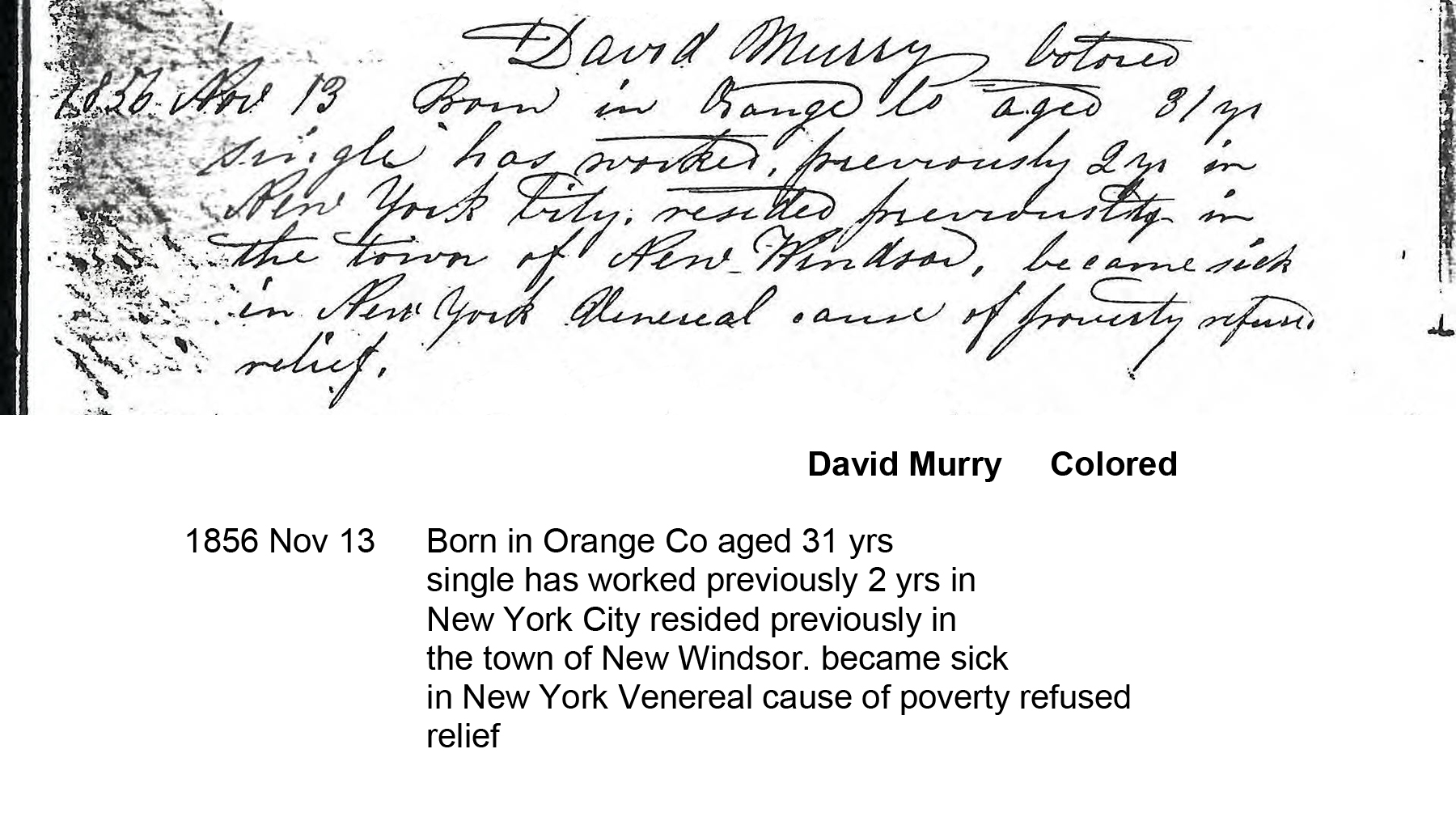

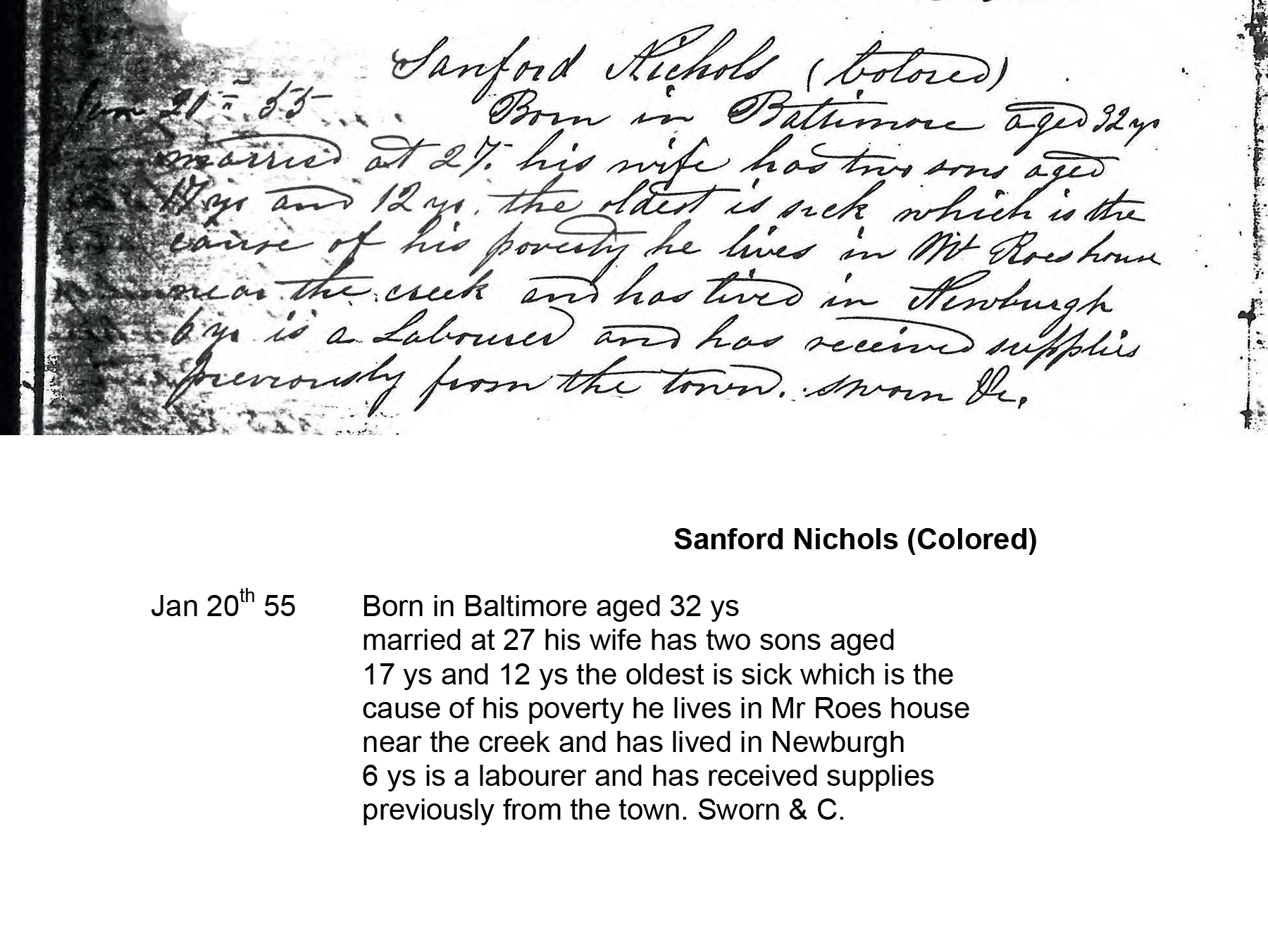

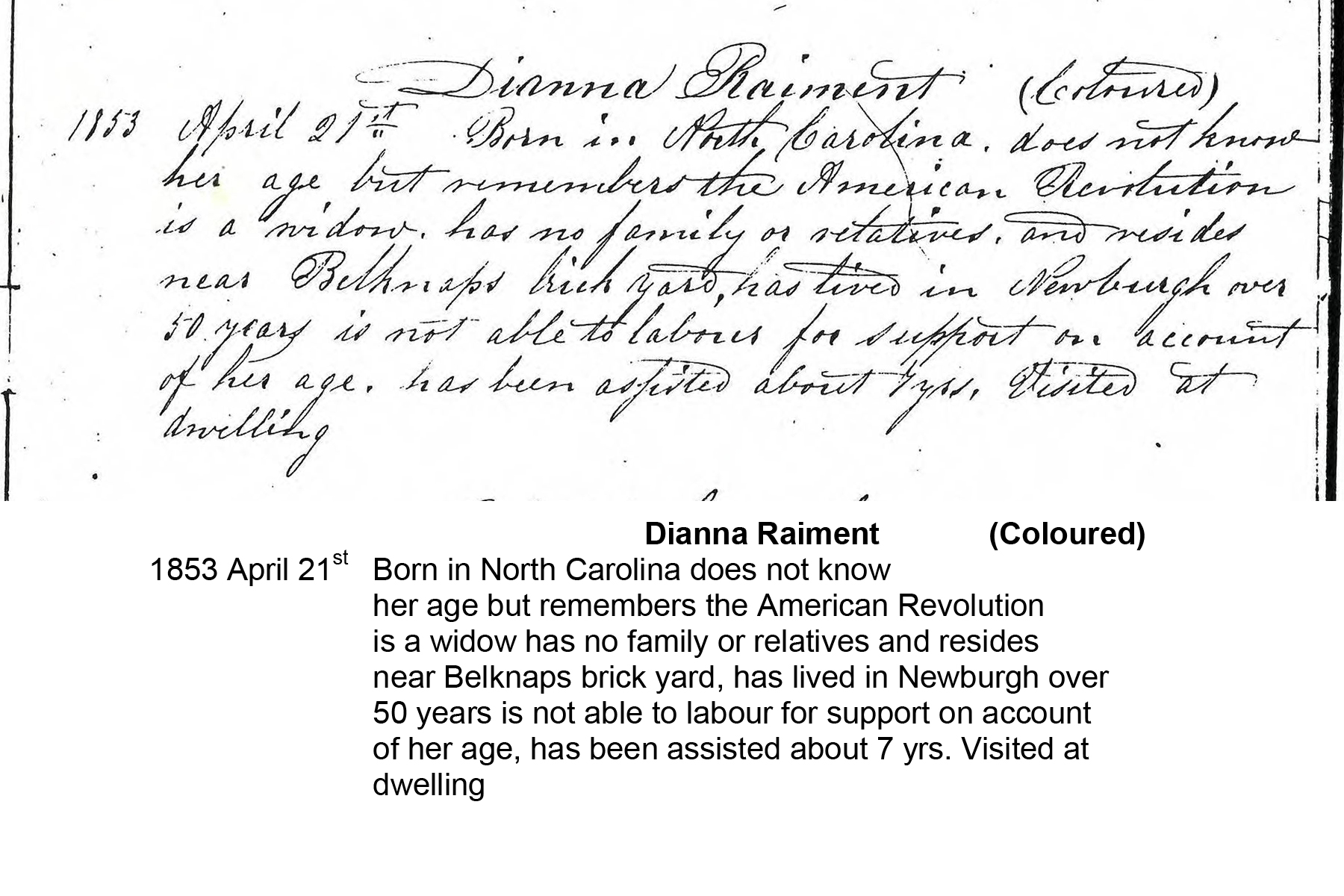

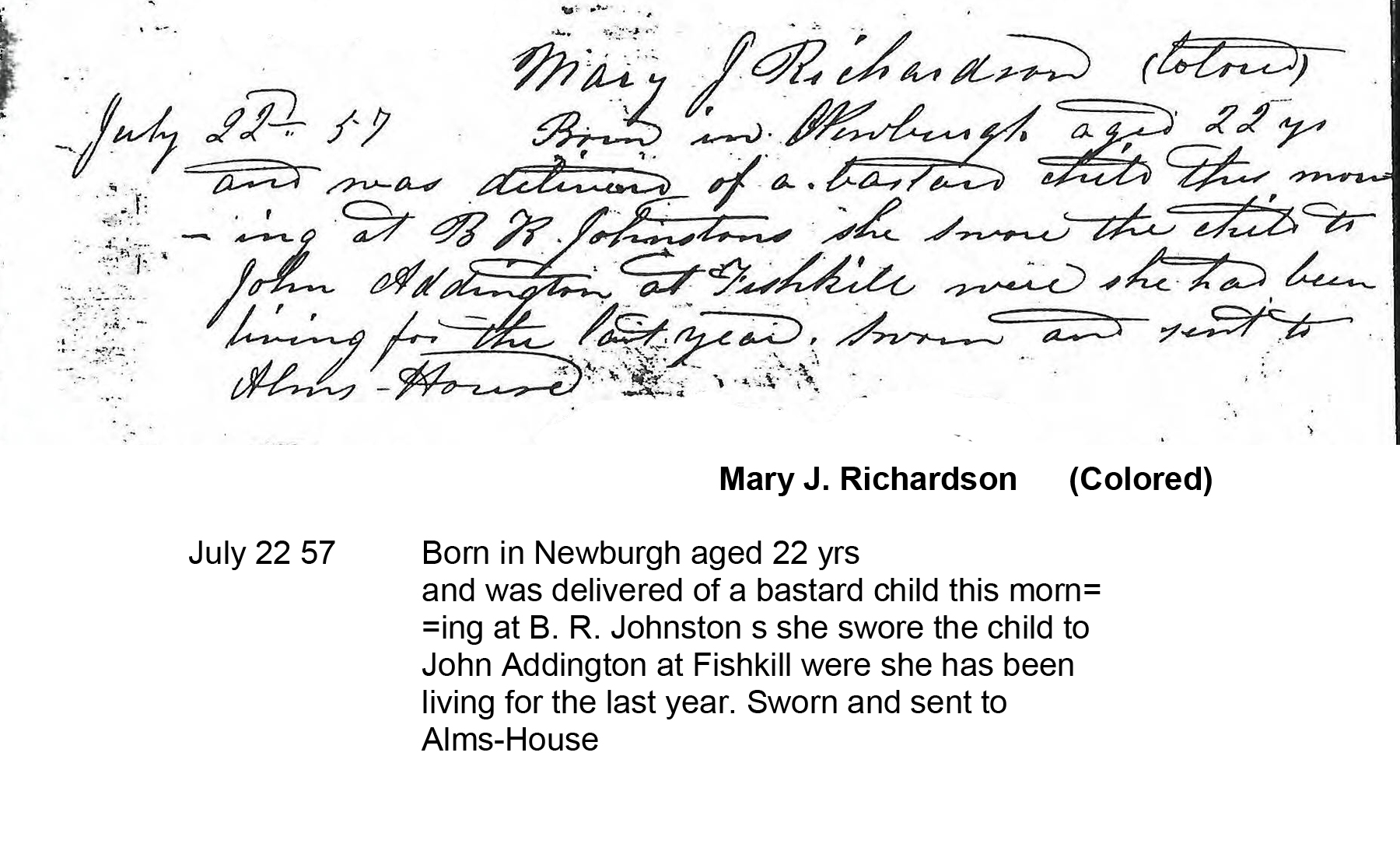

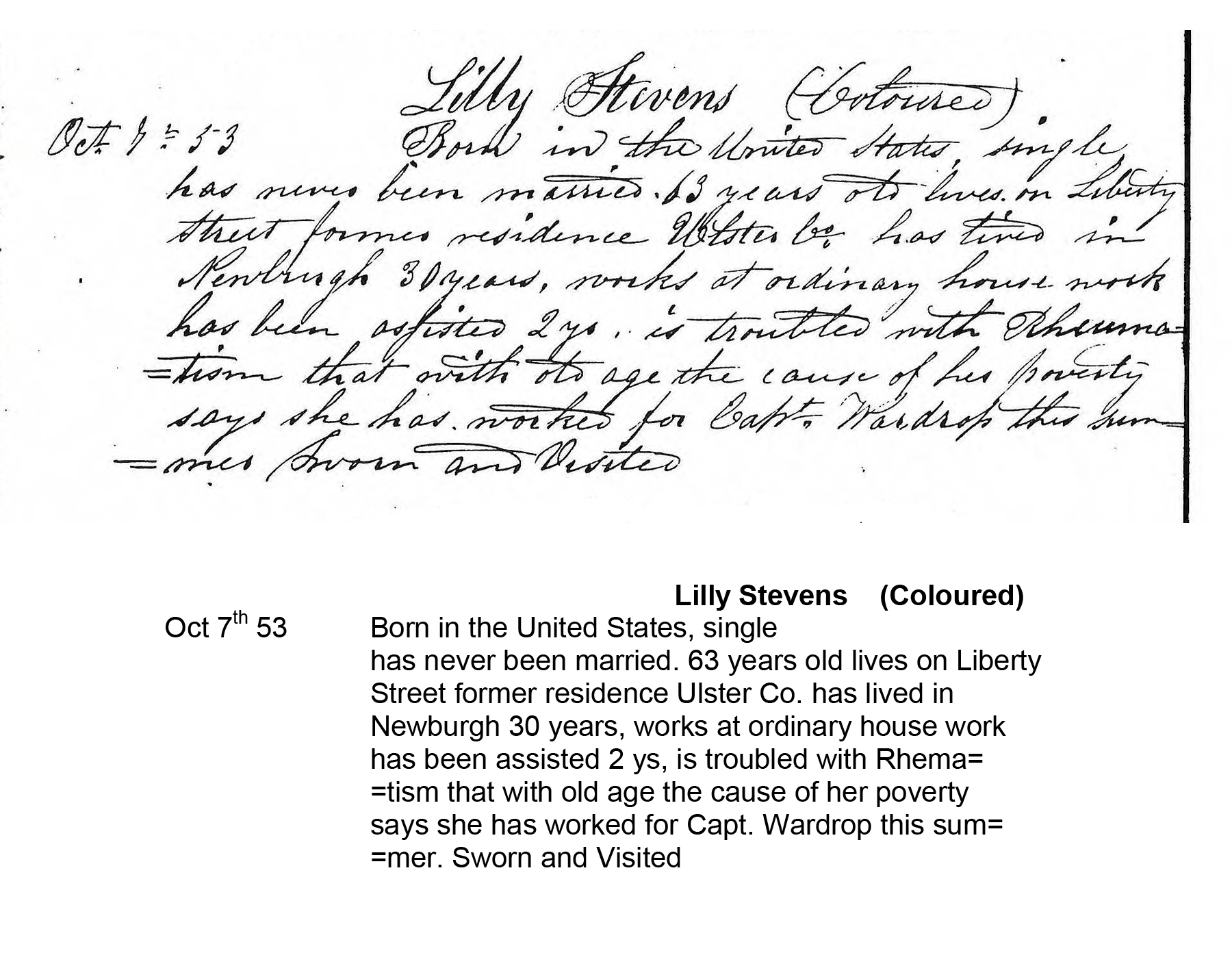

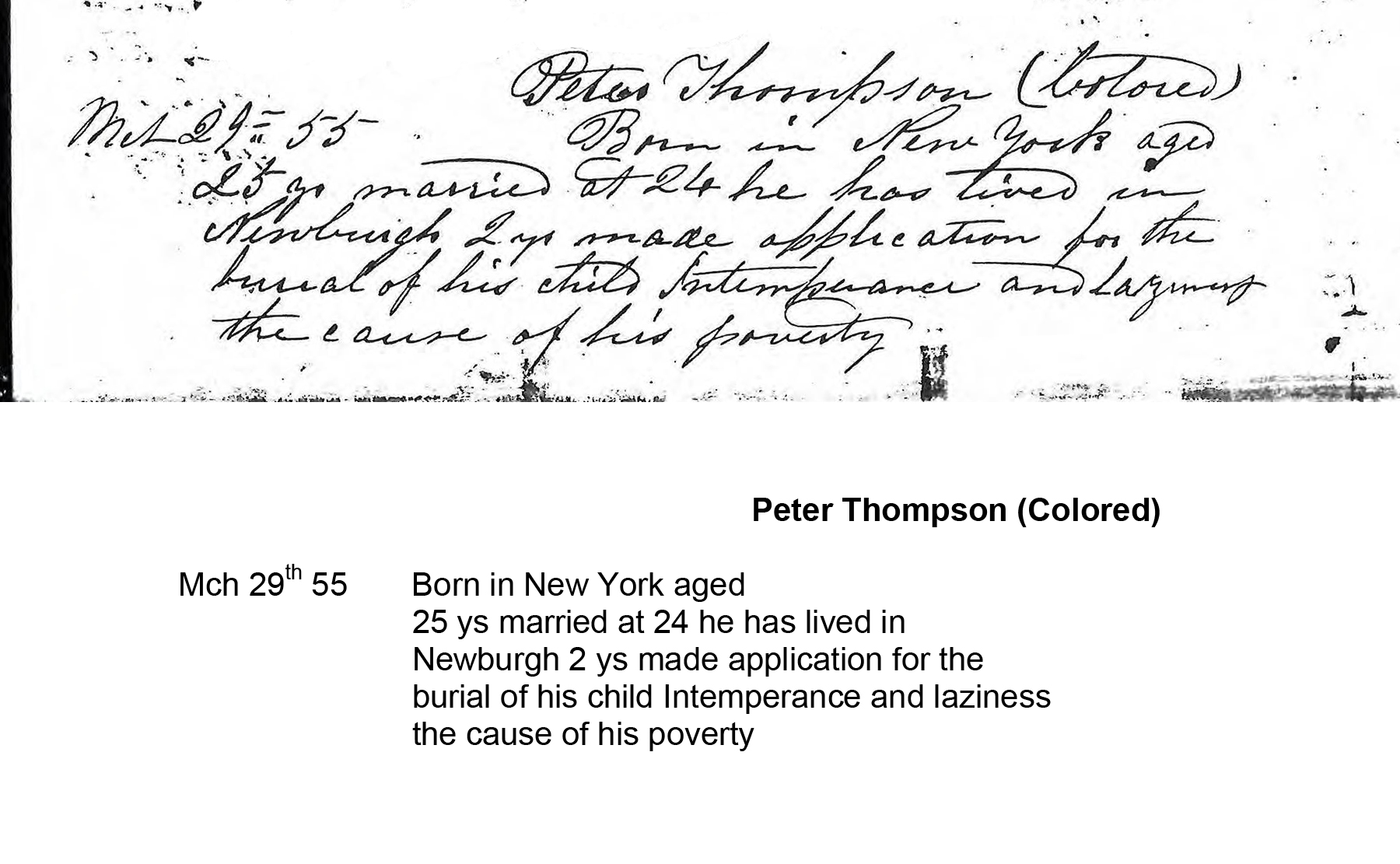

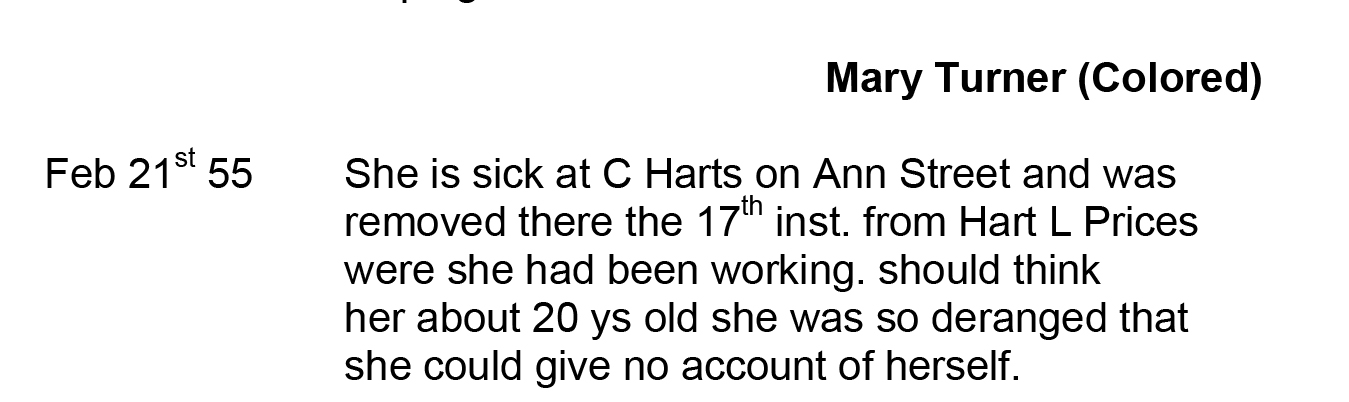

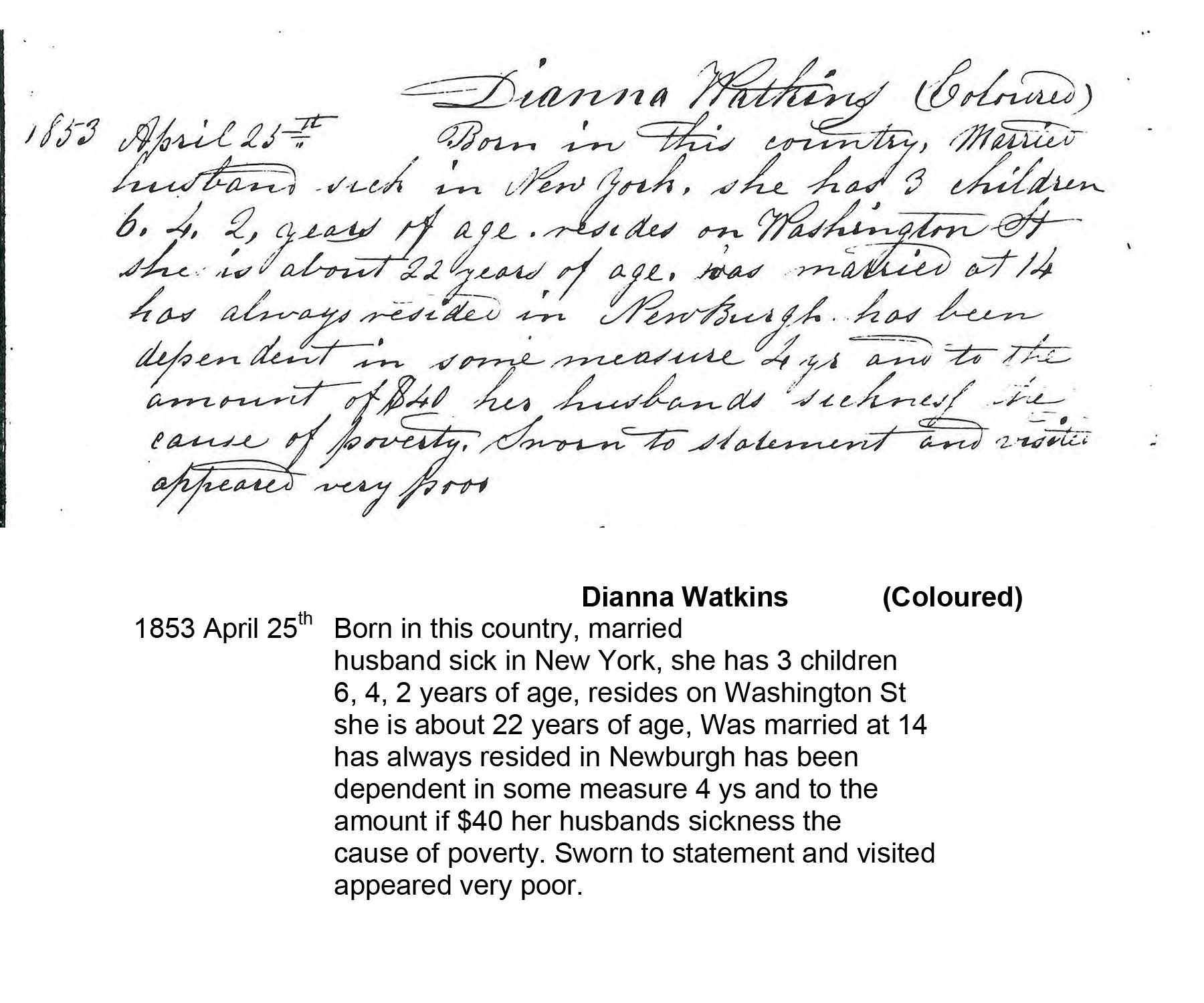

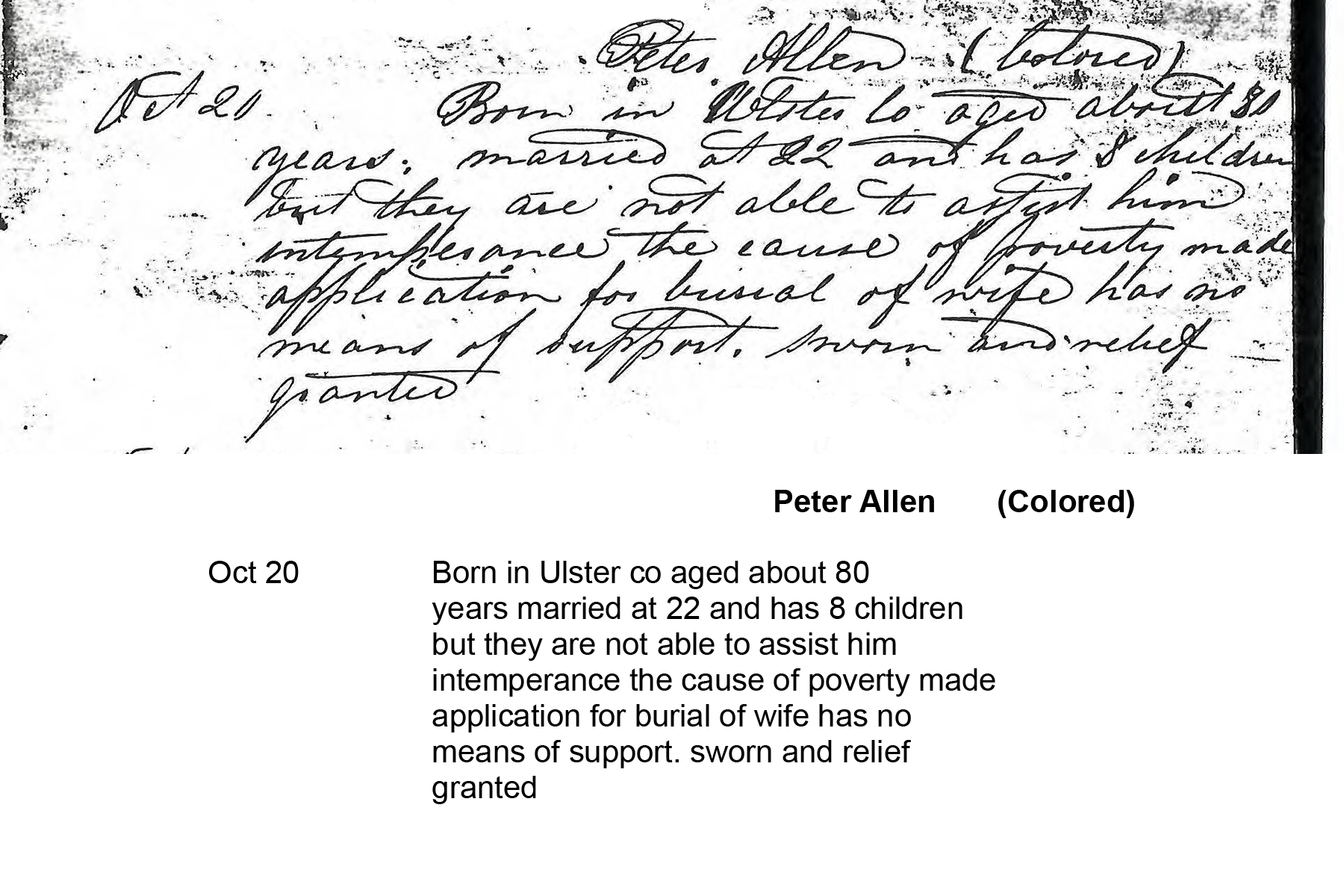

Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book, 1853-1858 New York Heritage Digital Collection

- Examiner’s Logbook transcriptions

- Orignal Writing from Examiner’s Logbook

- Elders-Transcribed from logbook for FTGU gatherings

- Data and Diagrams (additions in progress)

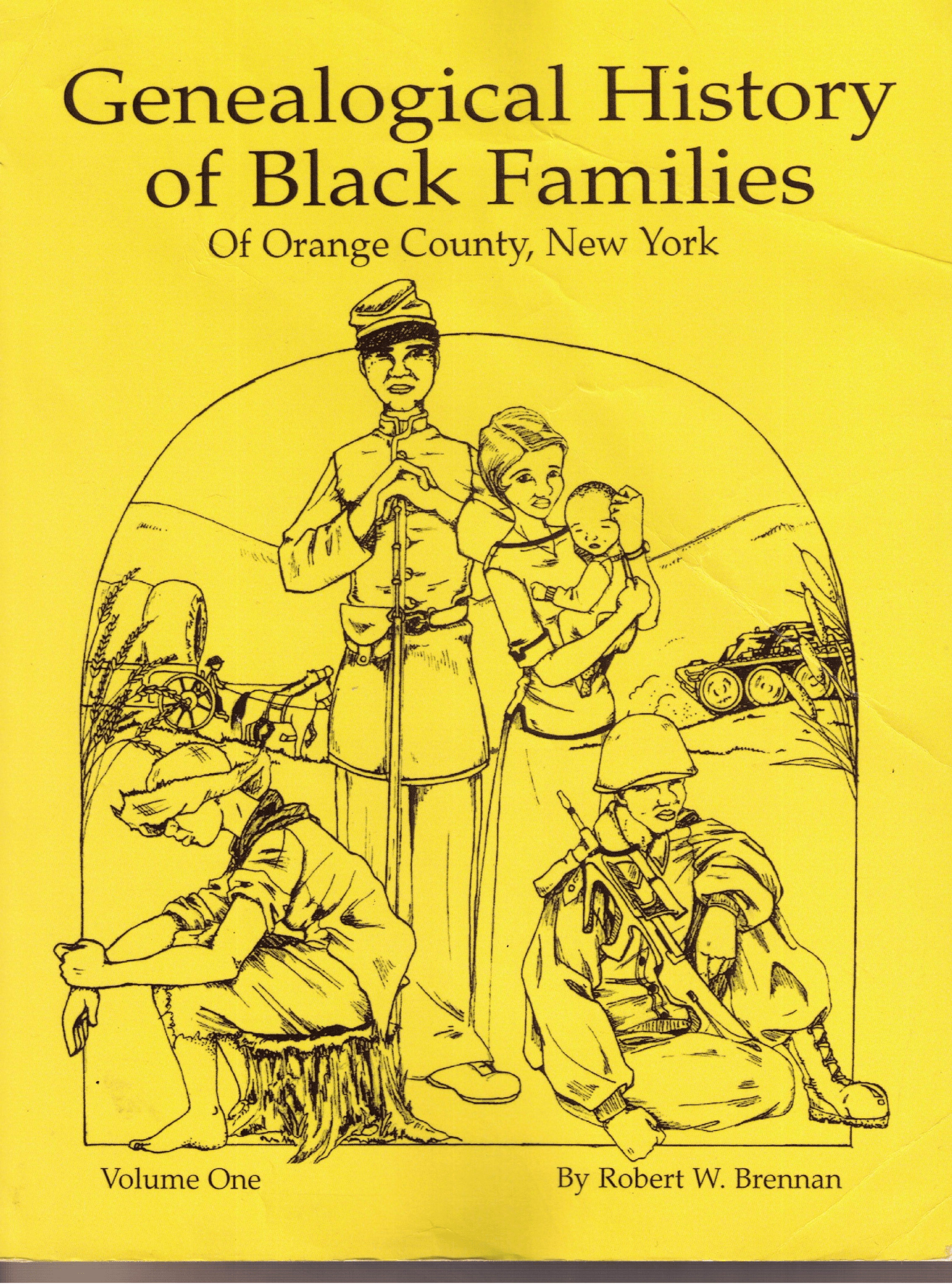

Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County, New York by Robert W. BrennanOrange County Geneological Society

- Volume 1, Ch 1 (in progress)

- Descendants of William Dolson

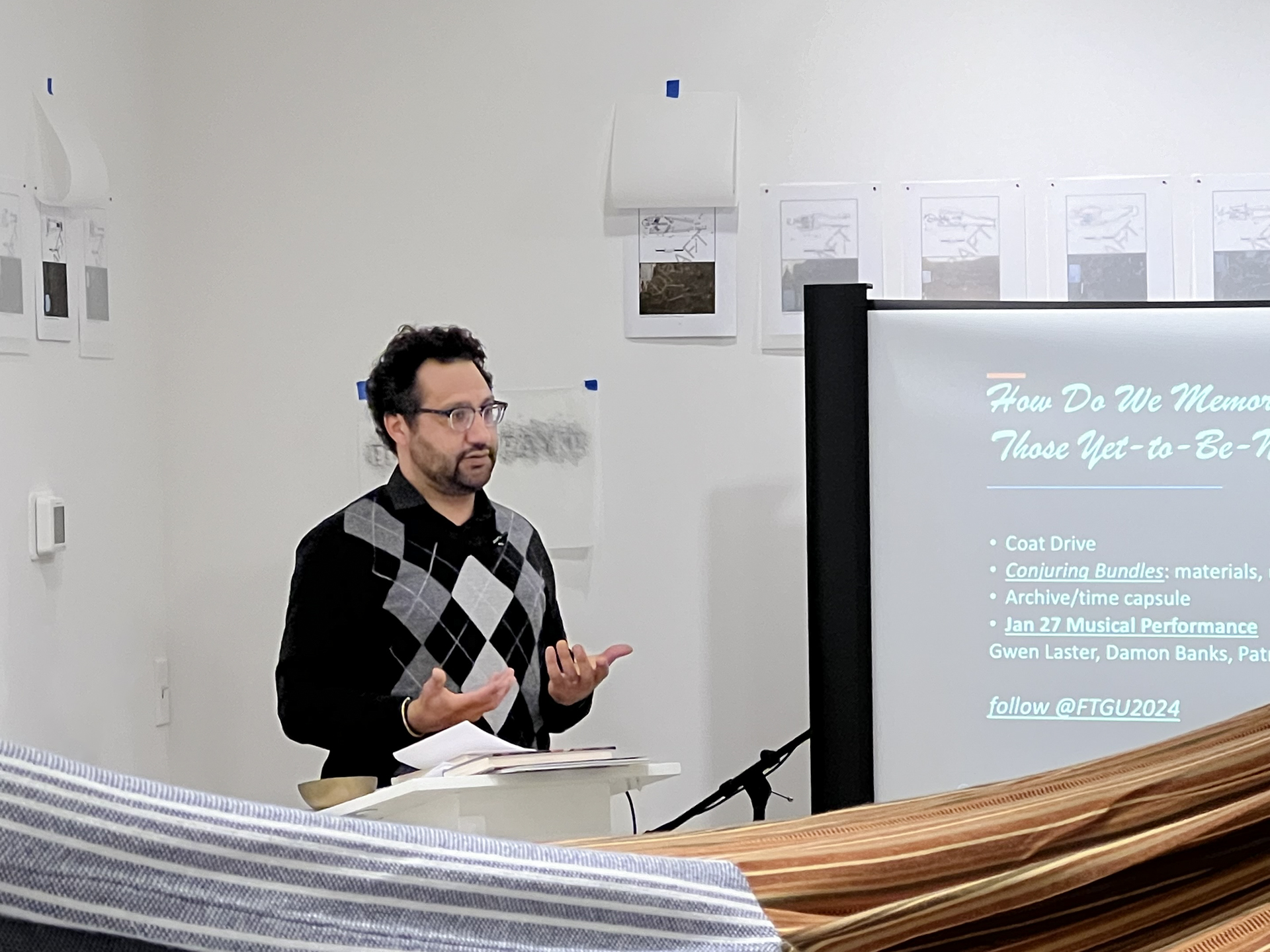

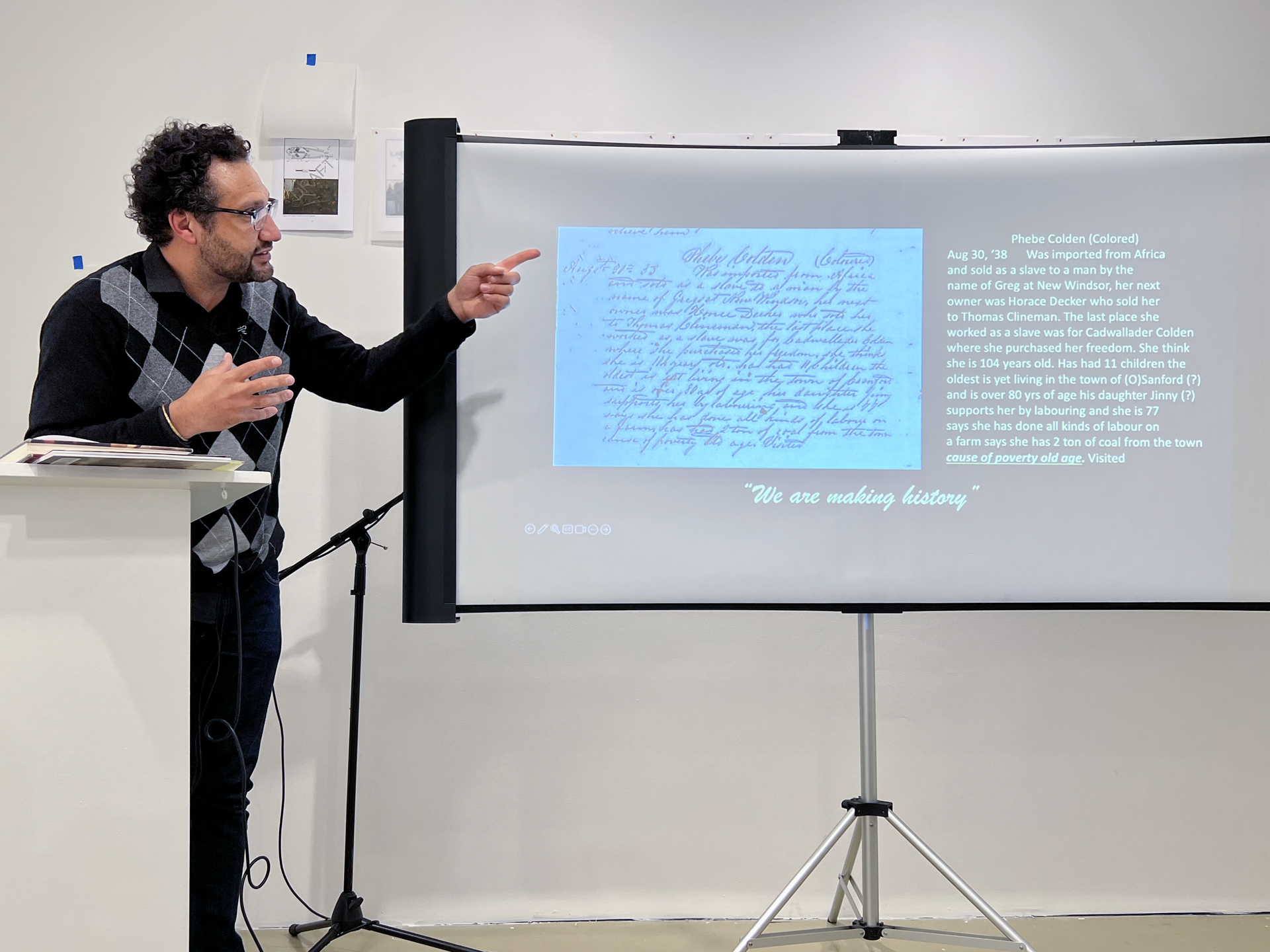

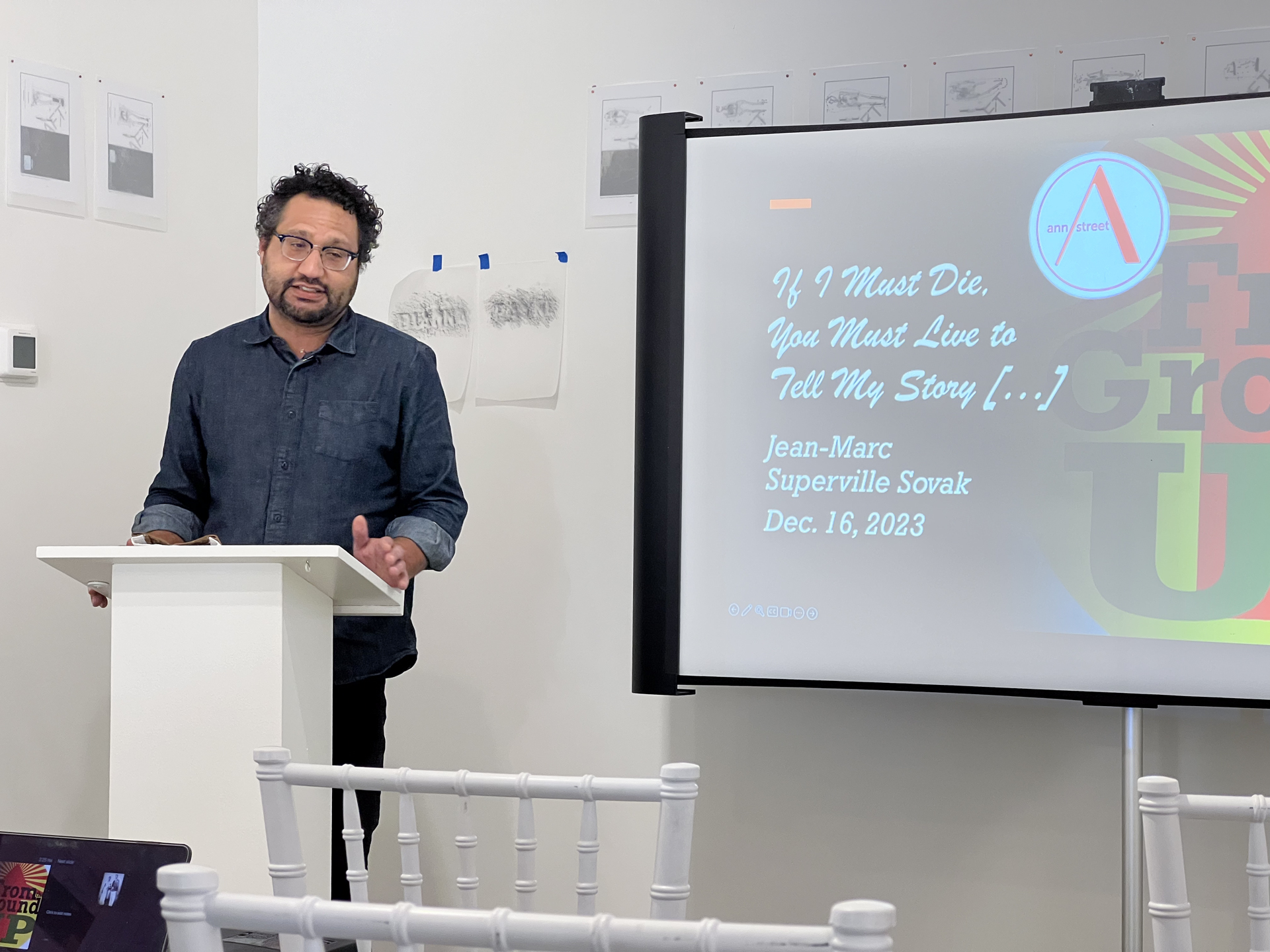

Slide excerpts from Superville Sovak’s research presentations

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

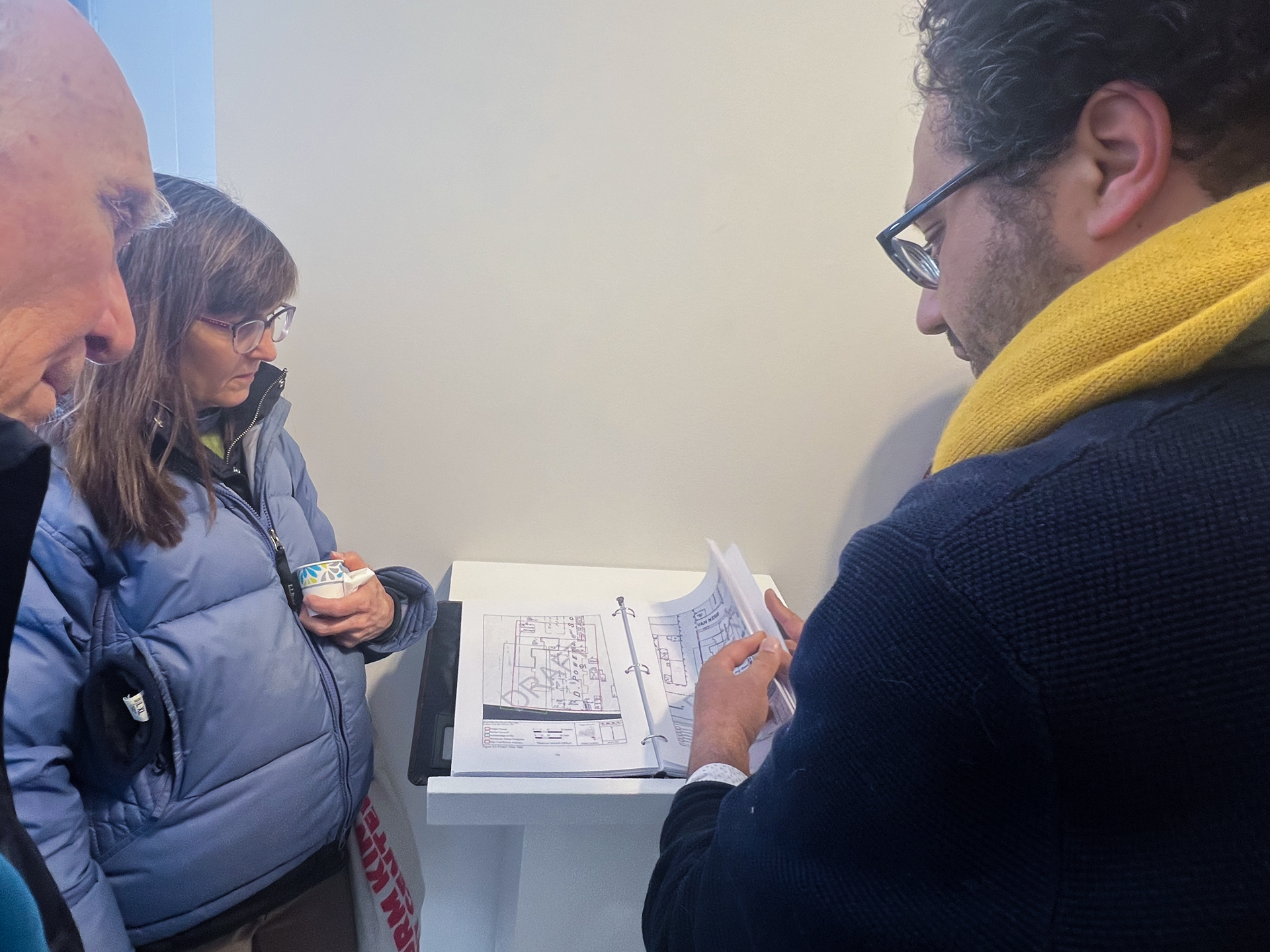

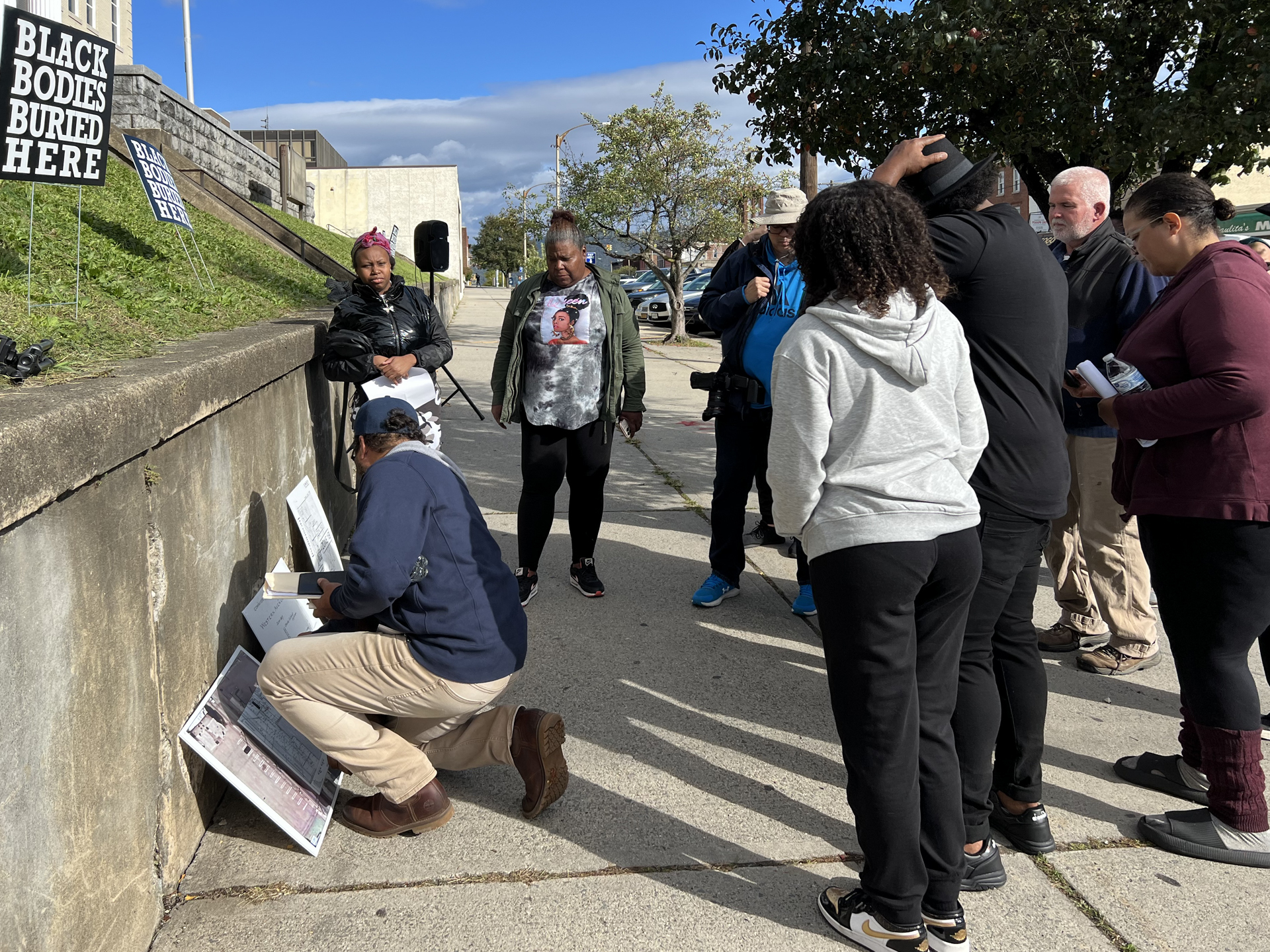

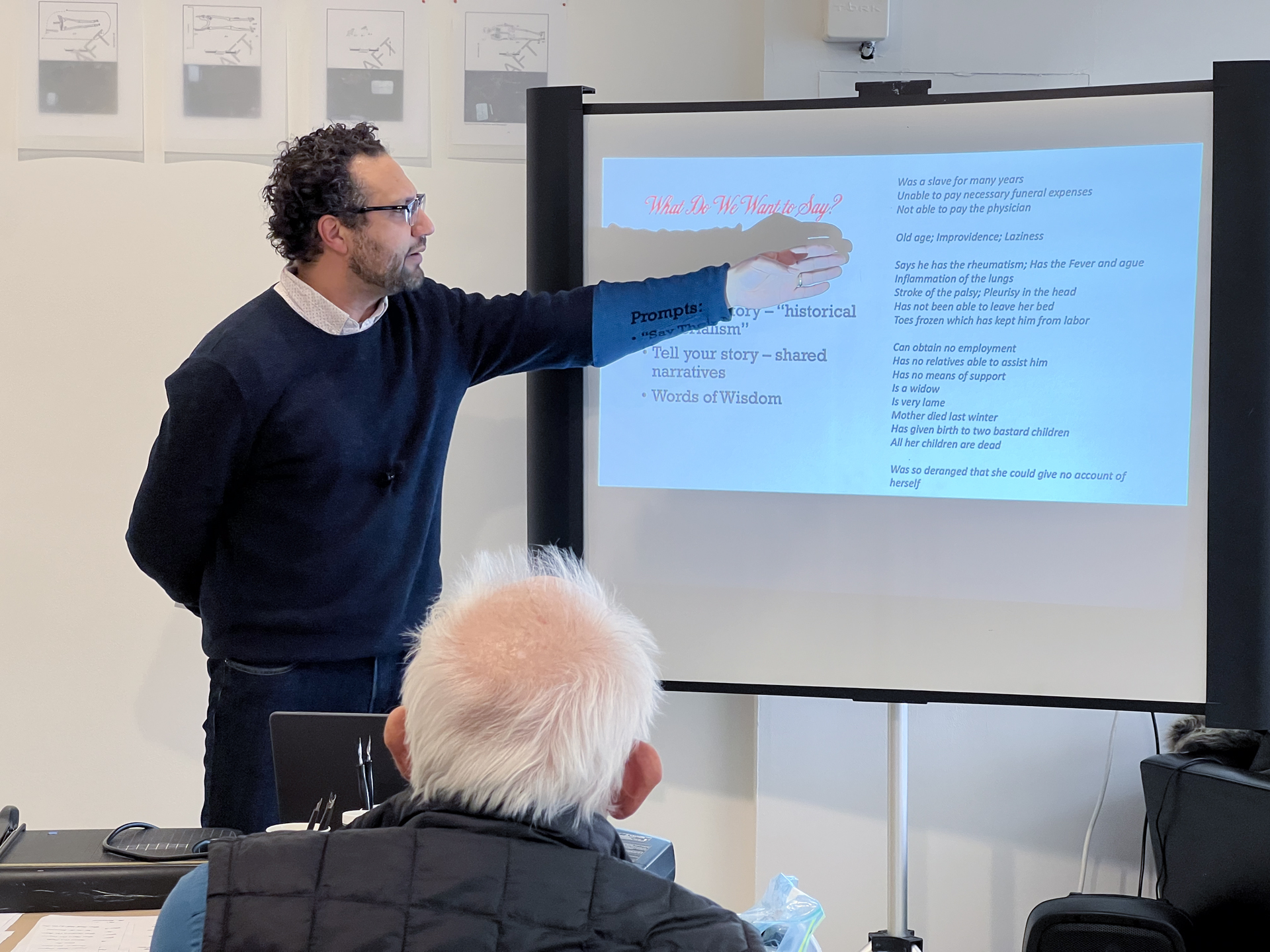

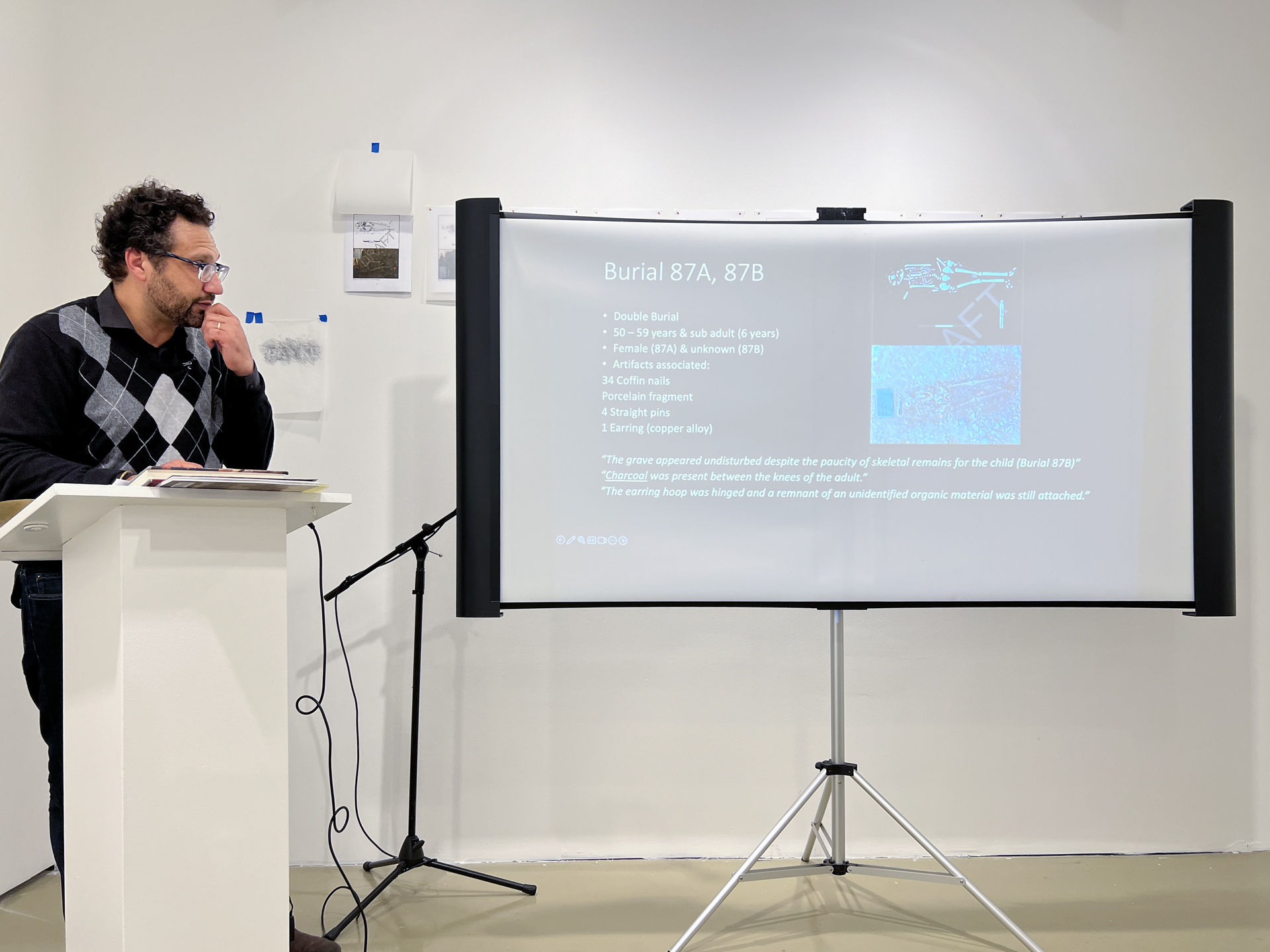

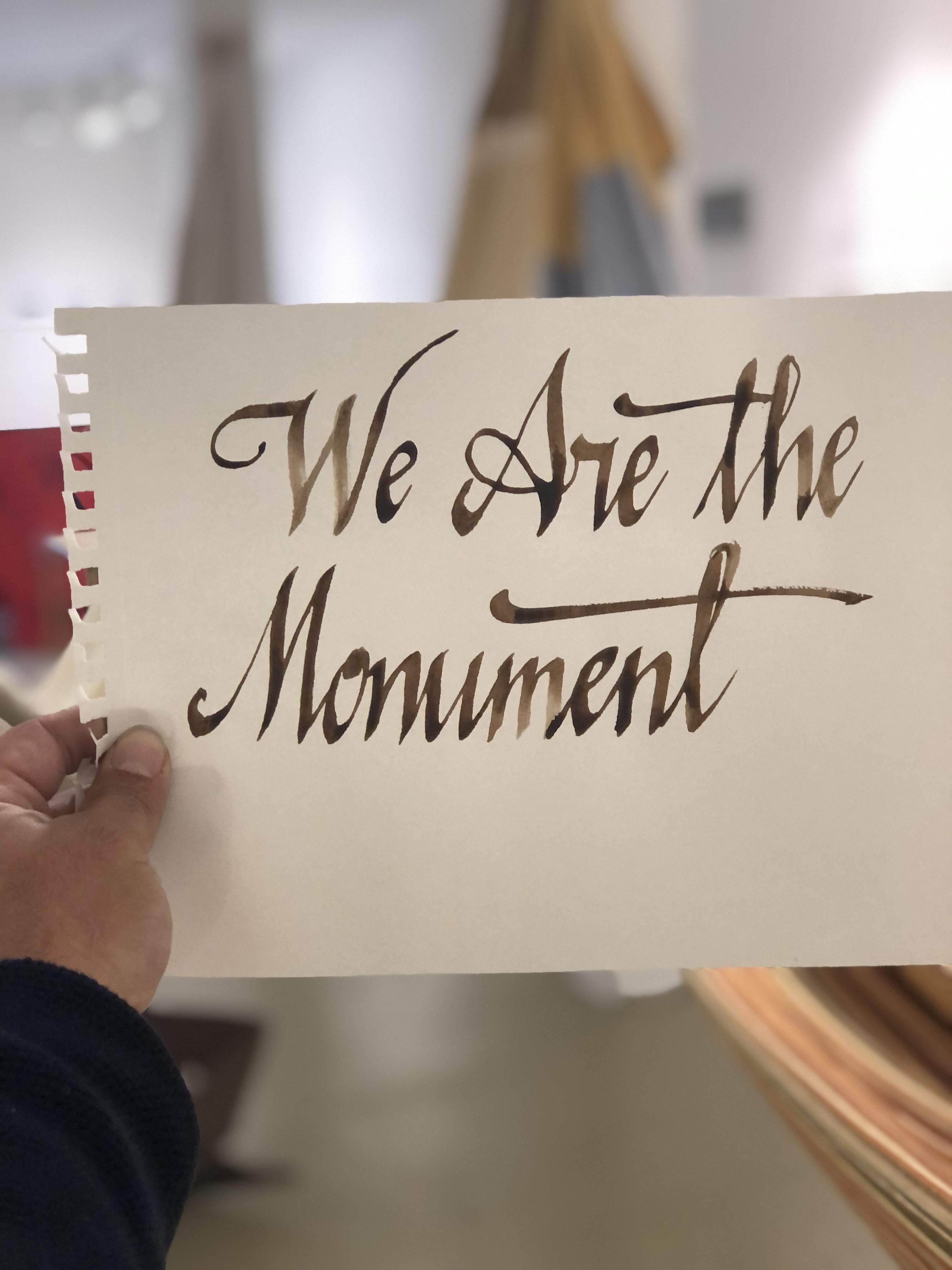

Photographs from From the Ground UP lectures and events free and open to the public

Photographs from From the Ground UP lectures and events free and open to the public

RESEARCH DESCRIPTION

There are three main primary research sources, which have allowed this project to speculate greatly on the lives of those Newburgh residents of African descent who specifically sought relief for the burial of their loved ones who were laid to rest in Newburgh’s “Colored Burial Ground”. To my knowledge, the names of these individuals - a direct result of this collective research - will now be available digitally to the public for the first time.

The first is The Archaeology, Osteology, and History of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground, prepared for the City of Newburgh by Landmark Archaeology, Inc., and submitted in 2017, a draft version of which is available HERE for download. Photographic portions of this volume were exhibited as evidentiary material for the duration of the project at Ann Street Gallery.

The second major source, the Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book, 1853-1858, is available at New York State Heritage Digital Collection*. While intended to serve as a form of accounting of those deemed worthy of charity by the Almshouse that operated Newburgh’s Colored Burial Ground, these examination records also serve retrospectively as micro-biographies of the lives of those who may have been laid to rest at the corner of Robinson Avenue and Broadway in Newburgh.

The third source is Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County, New York, by Robert W. Brennan, published by the Orange County Genealogical Society**, who generously allowed selected portions to be reproduced here. This volume has been indispensable to cross-referencing the names of those mentioned in the Almshouse records with generations of families of African descent who have called Newburgh and its surroundings home.

These resources have been greatly expanded thanks to all those who lent their expertise to this project. To them, a special thanks is due, including: Gabrielle Burton-Hill, Newburgh CBG (Colored Burial Ground) Committee member, Mike Van Dervoort, citizen genealogist and SPOMA (Sacred Place of My Ancestors) Committee member, and City of Newburgh Historian, Mary MacTamaney.

- Jean-Marc Superville Sovak

2023 ASG Artist Researcher in Residence

*Municipal Newburgh Records, Digital Collection, City of Newburgh, “Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book, 1853-1858”, New York Heritage Digital Collection, 1853-1858, https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/nhc/id/513/rec/3

**Orange County Genealogical Society, 101 Main St. Goshen, New York

Excerpts from the document (link to full report)

The Archaeology, Osteology, and History of

the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground

The Archaeology, Osteology, and History of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground, prepared for the City of Newburgh by Landmark Archaeology, Inc. in 2017 is perhaps the greatest volume of information to be printed out about a segregated burial ground designated for the city’s poorest in the Hudson Valley area. Though there are several historically recognized segregated burial grounds in the vicinity, such as the African Burial Ground in the town of Montgomery (stewarded by SPOMA, Sacred Place of My Ancestors) and the Pine Street Burial Ground (stewarded by Harambe), the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground is one of the rare few to have such an extensive survey prepared.

The study is divided into eleven chapters, of which the most relevant to this project were: Historic Context, Burial Descriptions, and Archaeological Research Issues Discussion.

Historic Context (pages 14-31)

This chapter was authored by Dr. Christina Ziegler-McPherson, who was invited to speak at one of this project's earliest community gatherings. While Ziegler-McPherson’s study on African American Life in Newburgh in the Mid-nineteenth Century (pages 19 -28) paints a rich portrait of Black life emerging from New York’s gradual abolition of slavery, her research into the identity of those buried at the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground presents a case for the unknowability of those individuals, concluding that, since “the kinds of historical evidence which normally helps to tell the history of a cemetery and those interred there – maps, city records, cemetery records, undertaker records, church records – largely do not exist […] we must be careful and cautious, and clearly note what is known from historical records and what cannot be known”.

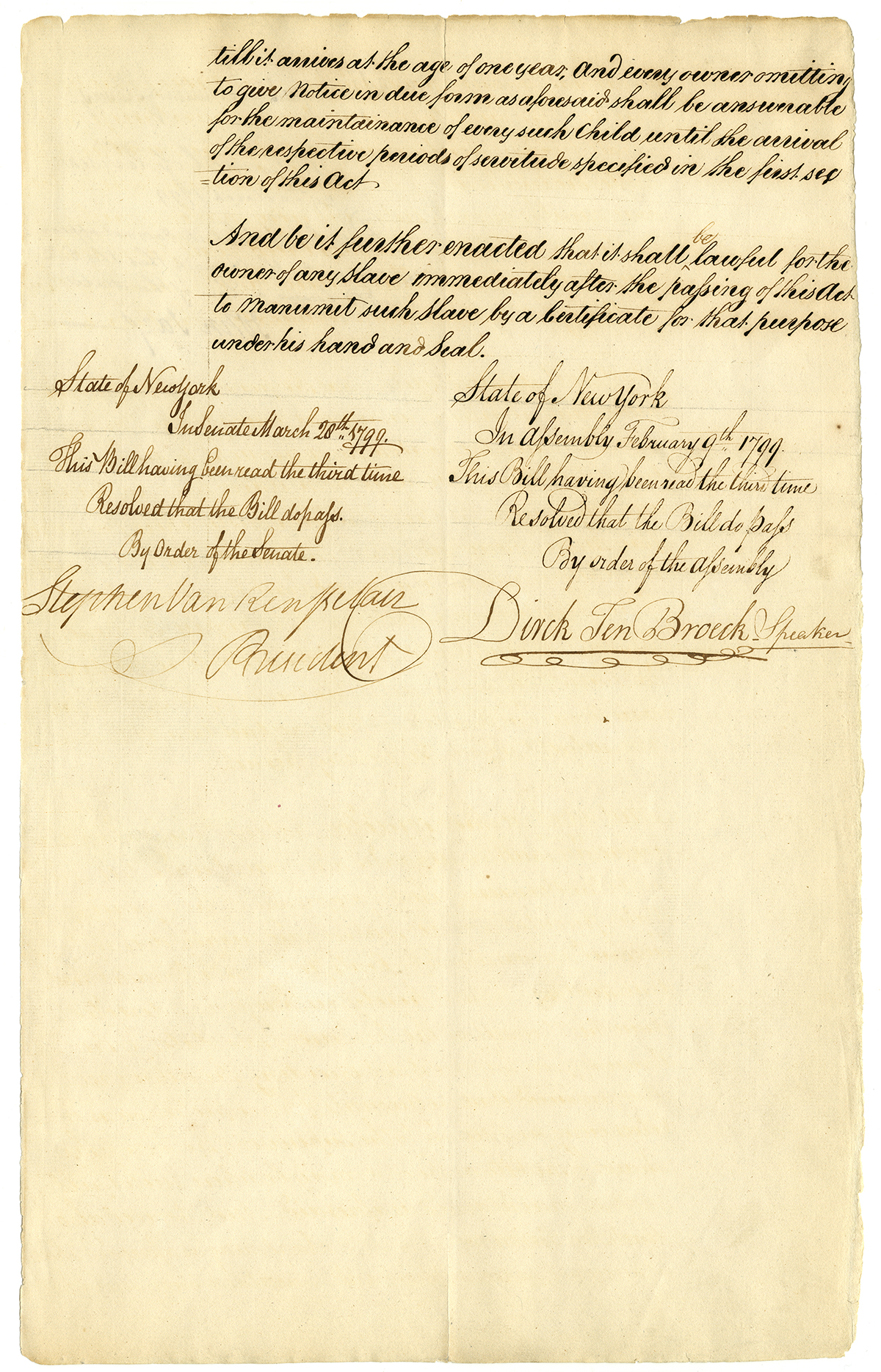

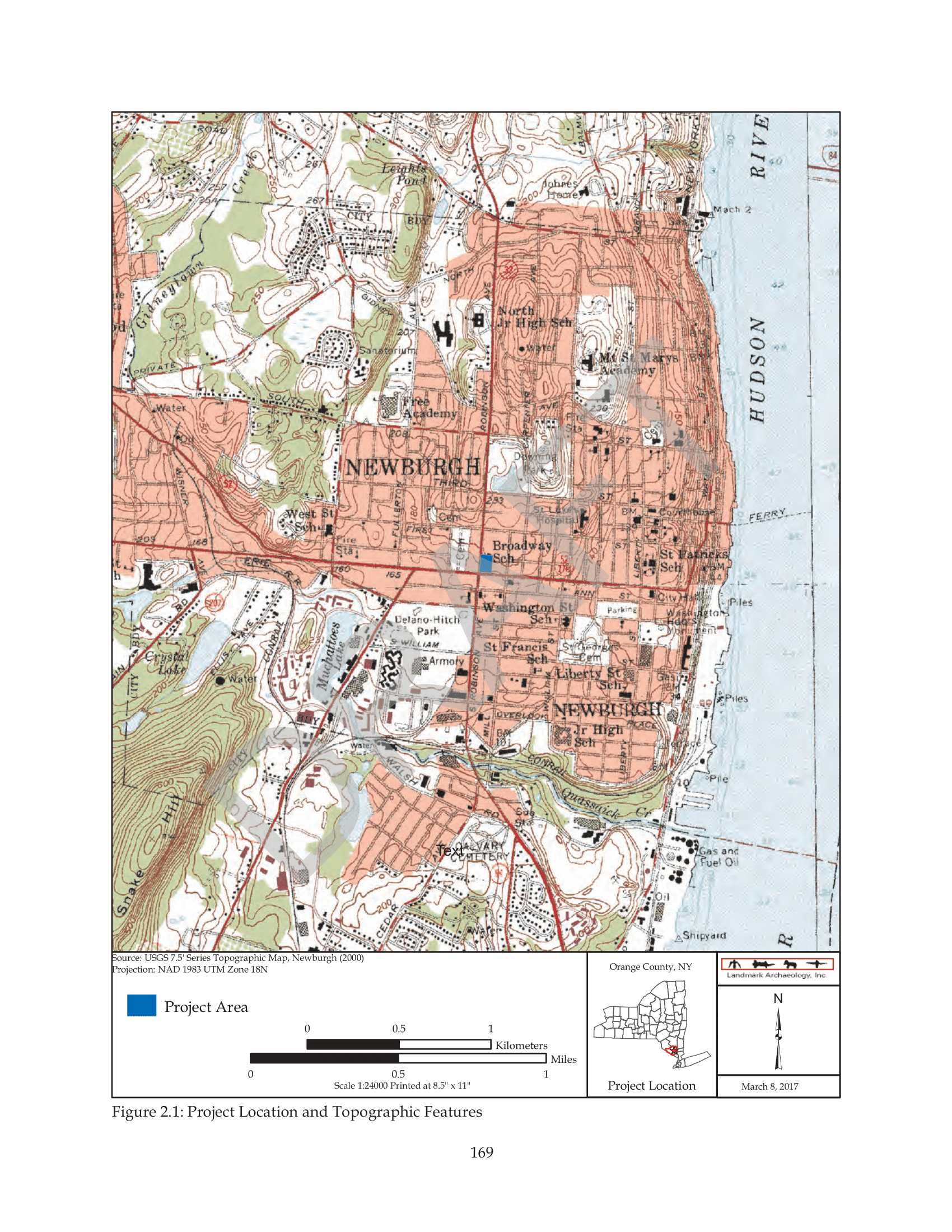

City of Newburgh map designating Newburgh Colored Burial Ground from 1869

from The Archaeology, Osteology, and History of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground

According to Ziegler-McPherson’s History of the Broadway School Site, “City health records note the burial of only six individuals at the ‘colored cemetery’ […] N. Carter, age 18 months, on March 16,

1867, and Jane Hart, age 1 year, on

April 25, 1867, Mary Jane Johnson, age 26 […] buried on October 19, 1866, Dianna

Payne, age 80, […] buried on October 20, 1866;

Jane Richardson, age 84, […] buried on October 22, probably 1866; and John Beuke or Burke, age 41, buried on July 31, 1867 (City of Newburgh Health Office n.d.). These are the only individuals known to have been buried on Broadway/Western Avenue, but this is more because the city did not require death certificates or burial permits until 1865.” (page 17, emphasis added)

Upon further investigation, I was able to locate one of these individuals, Dianna Payne, who is actually buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in neighboring New Windsor. It is possible her remains were removed and reinterred from Newburgh’s “colored burying ground’ [which] in city records appears in a June 1869 city surveyor’s map depicting the extension of Robinson Avenue through part of the cemetery (Caldwell 1869b).” (page 16)

Thanks to the Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book, 1853-1858 (see below) we also know that Jane Richardson was examined and visited by the Almshouse some thirteen years before her death. Of the other 60 names of “colored” individuals who were recorded as having been in the care of Newburgh’s Almshouse between 1853 to 1858, several of whom specifically presented themselves for relief for burial, it seems reasonable to assume that a number of them would have been buried in Newburgh Colored Burial Ground (see next chapter for a full list of those names.)

Dr. Ziegler-McPherson’s caution about “clearly not[ing] what is known from historical records and what cannot be known” demonstrates how the historical narrative of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground can and will continue to evolve as these details serve as addenda.

Jane Richardson, age 84, […] buried on October 22, probably 1866; and John Beuke or Burke, age 41, buried on July 31, 1867 (City of Newburgh Health Office n.d.). These are the only individuals known to have been buried on Broadway/Western Avenue, but this is more because the city did not require death certificates or burial permits until 1865.” (page 17, emphasis added)

Upon further investigation, I was able to locate one of these individuals, Dianna Payne, who is actually buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in neighboring New Windsor. It is possible her remains were removed and reinterred from Newburgh’s “colored burying ground’ [which] in city records appears in a June 1869 city surveyor’s map depicting the extension of Robinson Avenue through part of the cemetery (Caldwell 1869b).” (page 16)

Thanks to the Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book, 1853-1858 (see below) we also know that Jane Richardson was examined and visited by the Almshouse some thirteen years before her death. Of the other 60 names of “colored” individuals who were recorded as having been in the care of Newburgh’s Almshouse between 1853 to 1858, several of whom specifically presented themselves for relief for burial, it seems reasonable to assume that a number of them would have been buried in Newburgh Colored Burial Ground (see next chapter for a full list of those names.)

Dr. Ziegler-McPherson’s caution about “clearly not[ing] what is known from historical records and what cannot be known” demonstrates how the historical narrative of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground can and will continue to evolve as these details serve as addenda.

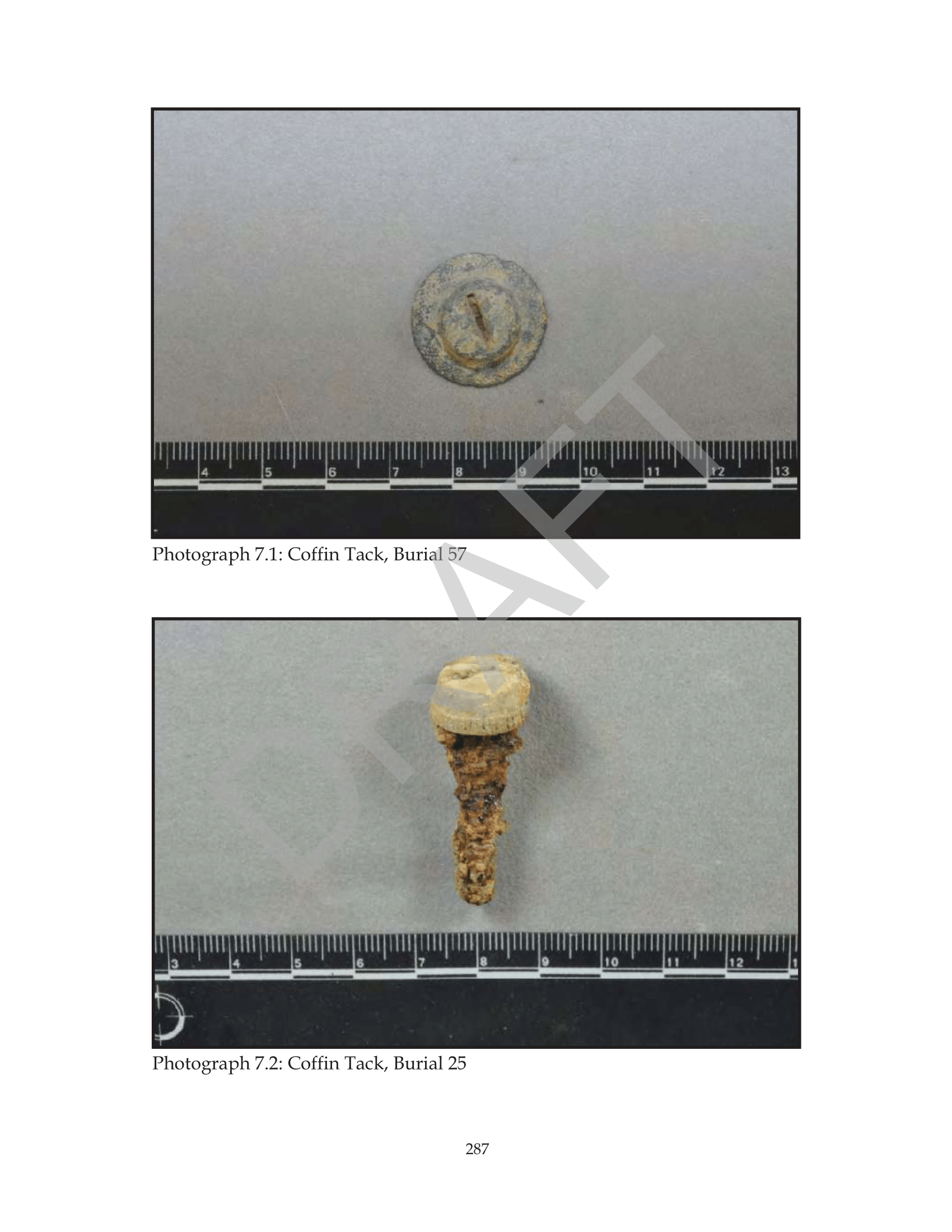

Coffin tacks in Burial Ground Report (left) and in the Ann Street Gallery exhbiition installation (right)

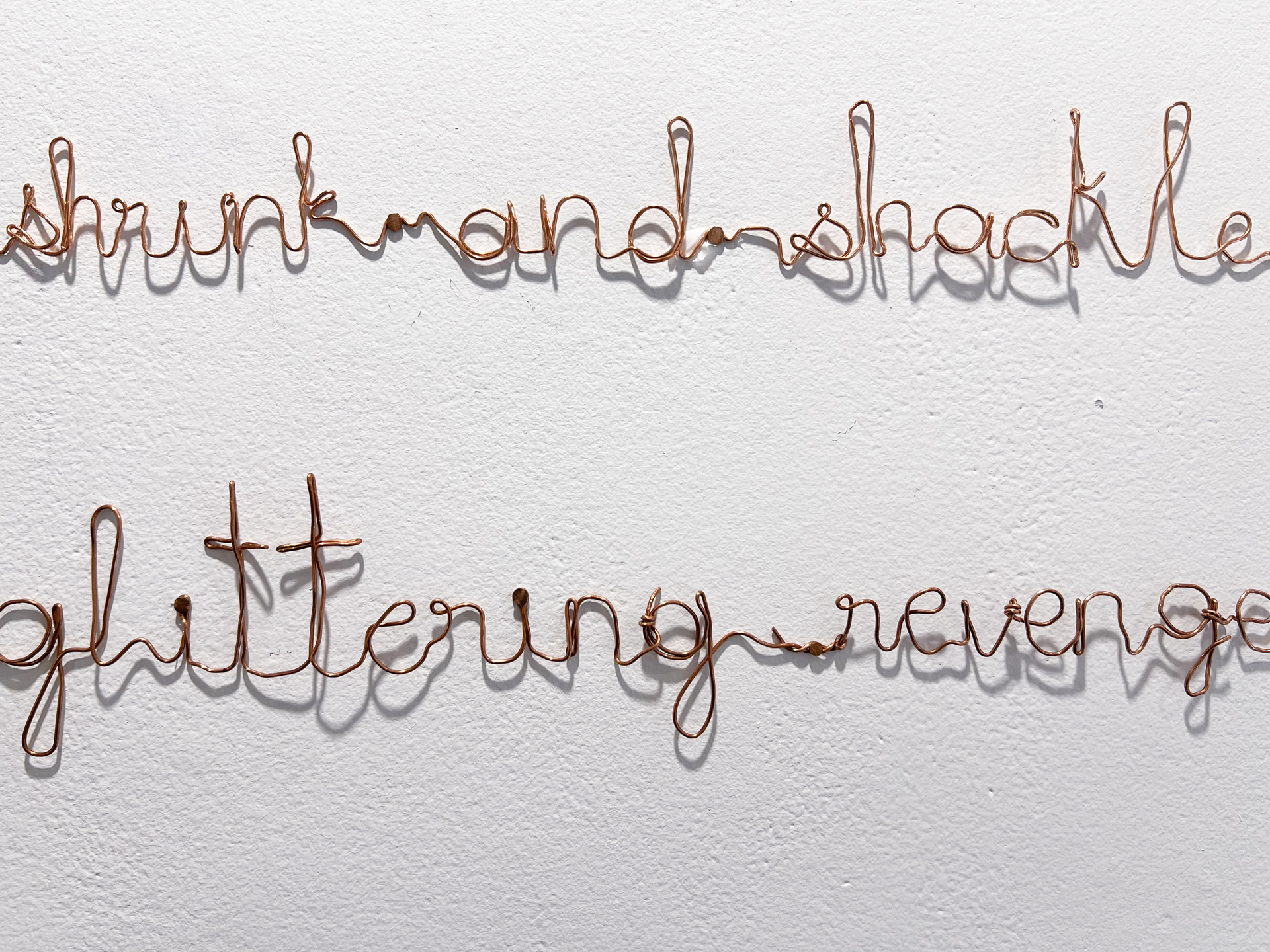

Boneyarn, by David Mills from The Ashland Poetry Press

excerpt from the poem,

To The Bones: About The Beads: Talking,

sculpted in repurposed copper wire by Superville Sovak

Burial Descriptions

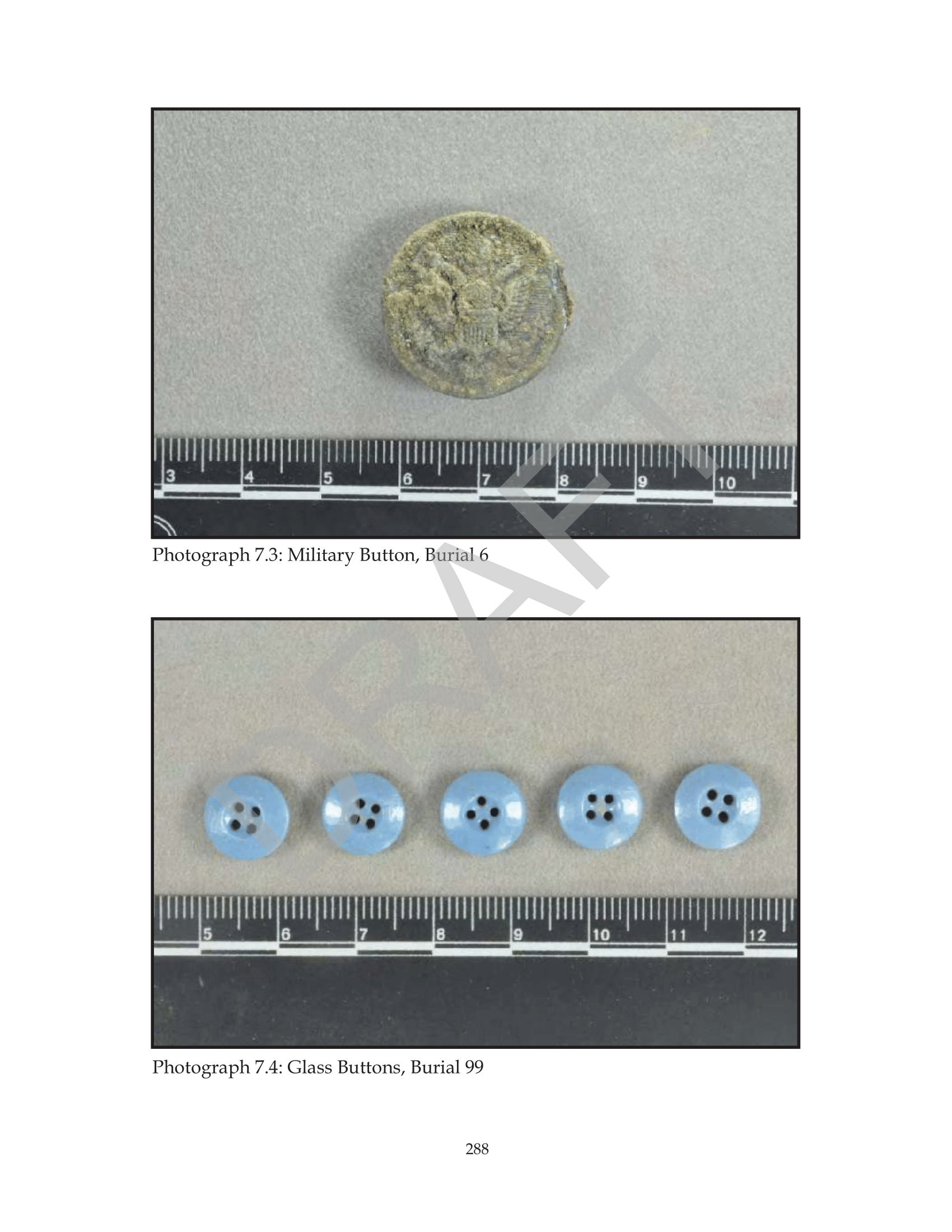

The individual analyses of each of the burials yield a wealth of evidence about the consistent care and dignity with which the individuals in Newburgh Colored Burial Ground were laid to rest.

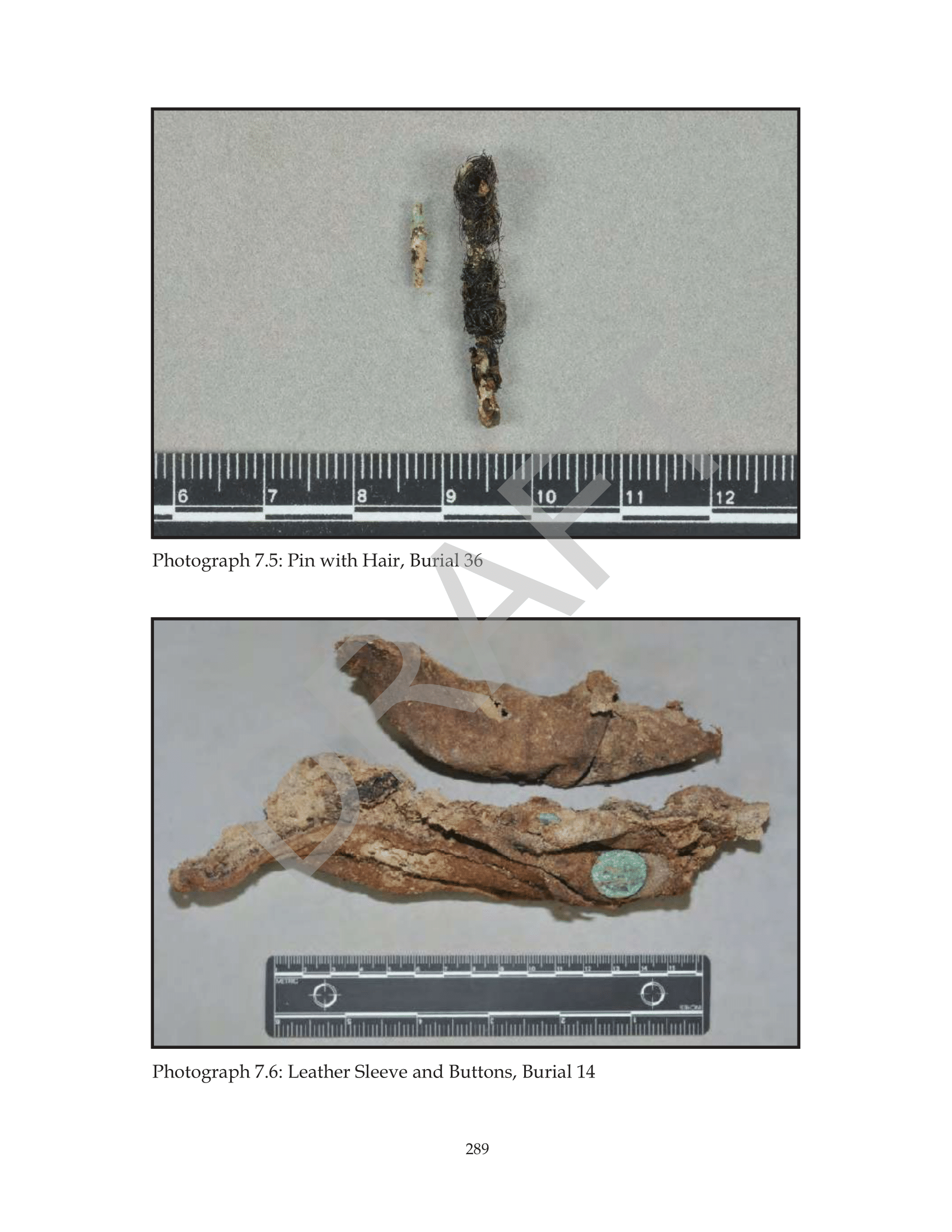

According to Landmark Archaeology, the most “abundant and ubiquitous in the cemetery is coffin hardware [and] the artifacts found in the burials indicate that the deceased were dressed either in clothing or wrapped in a shroud or winding sheet.” (page 155-157) These details directly inspired the installation at the gallery consisting of continuous shroud like fabric that wrapped the columned space and the use of copper nails to affix the photographic documentation of each burial in the gallery space in an effort to pose the question: “if you had nothing, what would you bury your loved one with?”

Other items such as pins, hair, buttons, jewelry, beads and coins – possessions of those considered the most dispossessed – leave a narrative spoken in a voice best articulated by the poet David Mills in his poetry collection Boneyarn.

That clear glass bead with a clear green heart in your grave?

That ocean we could not see

when we was dragged across

is a drop we shrunk and shackled

It’s now our glittering revenge

(excerpt from David Mills poem,

The individual analyses of each of the burials yield a wealth of evidence about the consistent care and dignity with which the individuals in Newburgh Colored Burial Ground were laid to rest.

According to Landmark Archaeology, the most “abundant and ubiquitous in the cemetery is coffin hardware [and] the artifacts found in the burials indicate that the deceased were dressed either in clothing or wrapped in a shroud or winding sheet.” (page 155-157) These details directly inspired the installation at the gallery consisting of continuous shroud like fabric that wrapped the columned space and the use of copper nails to affix the photographic documentation of each burial in the gallery space in an effort to pose the question: “if you had nothing, what would you bury your loved one with?”

Other items such as pins, hair, buttons, jewelry, beads and coins – possessions of those considered the most dispossessed – leave a narrative spoken in a voice best articulated by the poet David Mills in his poetry collection Boneyarn.

That clear glass bead with a clear green heart in your grave?

That ocean we could not see

when we was dragged across

is a drop we shrunk and shackled

It’s now our glittering revenge

(excerpt from David Mills poem,

To The Bones: About The Beads: Talking)

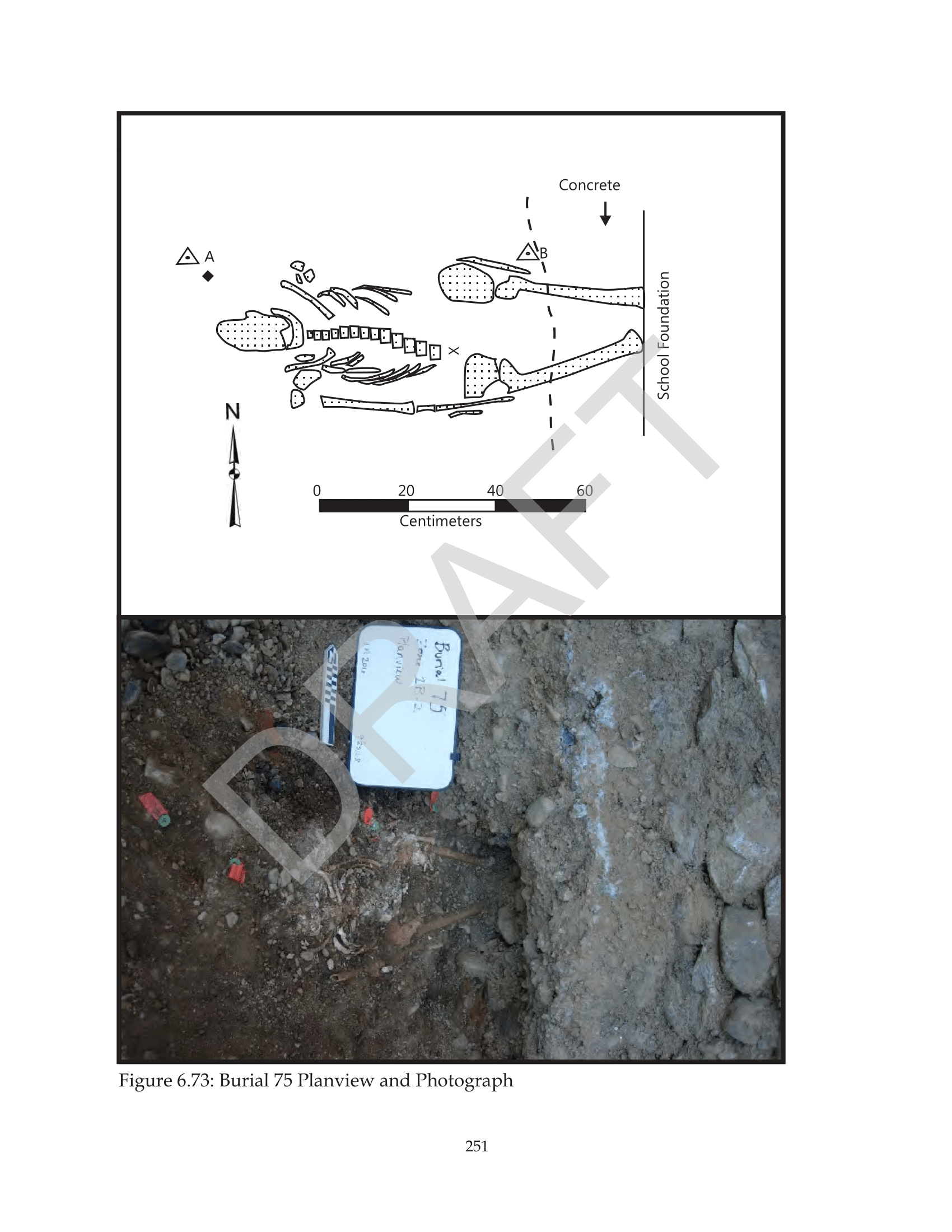

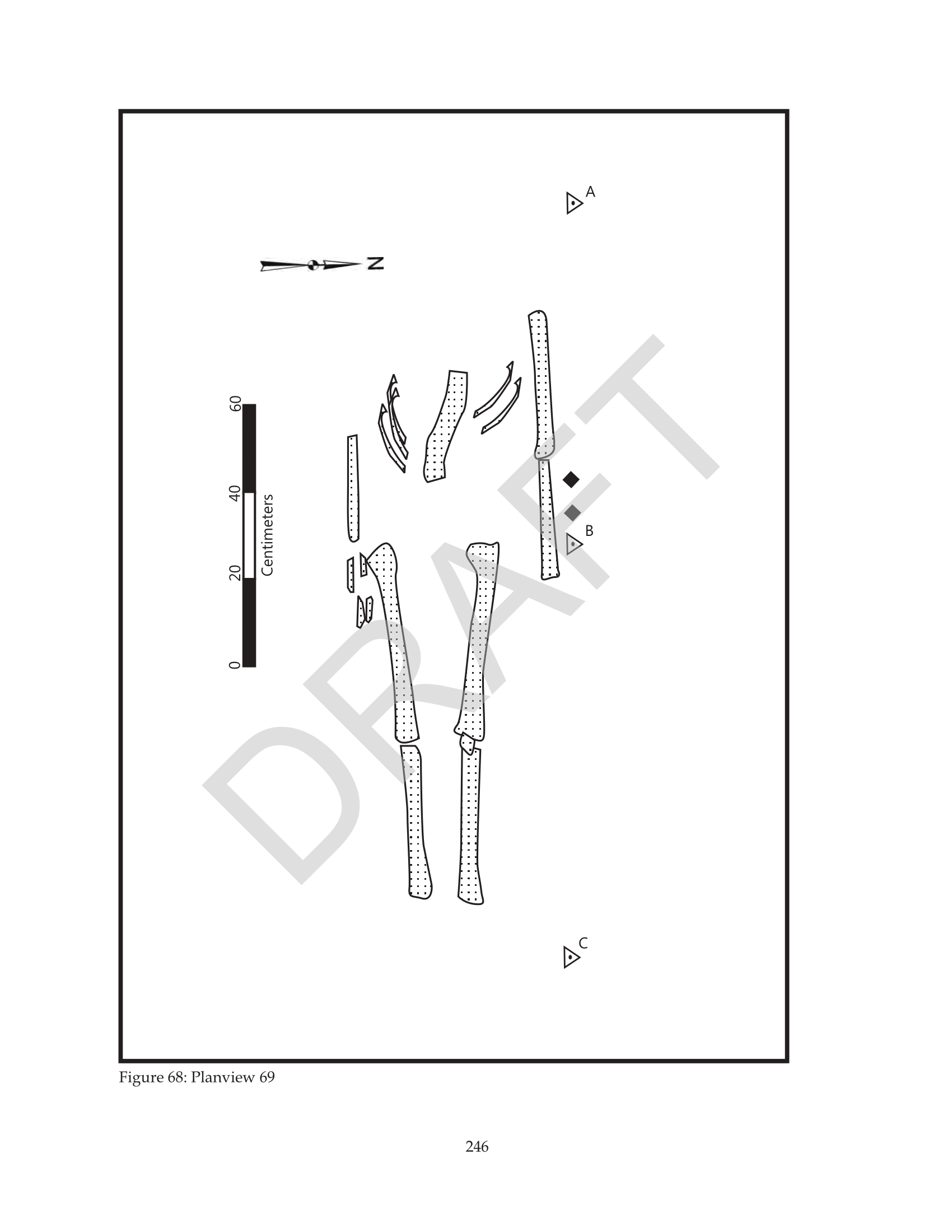

Diagrams and maps of project parcel, excavation locations, and burial sites, highlighting Burial Site 29

Burial site 29 and 15 burial sites not excavated due to existing within or below building foundations

Archaeological

Research Issues Discussion (pages 136-140)

This chapter presents a good case for which, as it is quoted, “it is through death that the social relationships of the living are defined and expressed.” Several details described in this chapter provided a deeper understanding of the relationship among those were laid to rest and those who had laid them to rest.

In this chapter, we learn that “all but one of the deceased were buried in coffins with the head to the west, and facing east. The exception is Burial 29, in which the deceased is facing west.” Who was laid in Burial 29? According to the Catholic Encyclopedia: “[I]f the corpse be that of a layman, the feet are to be turned towards the altar; if on the other hand the corpse be that of a priest, then the position is reversed, the head being towards the altar.”* We can speculate that among those Black residents of Newburgh who placed feet of their loved ones toward the rising sun of resurrection in observing Christian religious practices as they understood them, there was the one individual in Burial 29 who lived a life worthy of being recognized in that tradition as that of a spiritual leader.

The Newburgh Colored Burial Ground Site Map (page 173) laid the framework for the initial gallery exhibition design for the project in Ann Street Gallery. The spatial organization of the 108 pages representing the 115 individuals (some in double burials) displayed contiguously so that each burial was represented next to the burial it once laid next to, was an effort to represent these individuals as close as possible to the original site as it was organized when it was once intact. This includes those burials existing within or below concrete building foundations. Spouses, parents and children, families who may have been laid to rest side by side, were together again in the Gallery installation as they await reburial.

*Thurston, Herbert. "Christian Burial." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908

This chapter presents a good case for which, as it is quoted, “it is through death that the social relationships of the living are defined and expressed.” Several details described in this chapter provided a deeper understanding of the relationship among those were laid to rest and those who had laid them to rest.

In this chapter, we learn that “all but one of the deceased were buried in coffins with the head to the west, and facing east. The exception is Burial 29, in which the deceased is facing west.” Who was laid in Burial 29? According to the Catholic Encyclopedia: “[I]f the corpse be that of a layman, the feet are to be turned towards the altar; if on the other hand the corpse be that of a priest, then the position is reversed, the head being towards the altar.”* We can speculate that among those Black residents of Newburgh who placed feet of their loved ones toward the rising sun of resurrection in observing Christian religious practices as they understood them, there was the one individual in Burial 29 who lived a life worthy of being recognized in that tradition as that of a spiritual leader.

The Newburgh Colored Burial Ground Site Map (page 173) laid the framework for the initial gallery exhibition design for the project in Ann Street Gallery. The spatial organization of the 108 pages representing the 115 individuals (some in double burials) displayed contiguously so that each burial was represented next to the burial it once laid next to, was an effort to represent these individuals as close as possible to the original site as it was organized when it was once intact. This includes those burials existing within or below concrete building foundations. Spouses, parents and children, families who may have been laid to rest side by side, were together again in the Gallery installation as they await reburial.

*Thurston, Herbert. "Christian Burial." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908

Items found in NCBG burial (page 291); Offering brought by FTGU participant (see more community offerings at the bottom of this page)

The questions in this chapter were also instrumental for

this project in designing the kind of interaction with the public that served

to conjure the stories of those buried in Newburgh Colored Burial Ground. The

reference to “conjuring bundles”, items found in burials thought to be of

significance to those individuals who were laid to rest, became a theme for

this project with which the public was invited to participate by offering items

that symbolically reflected this burial practice accompanied by “letters to the

Ancestors” penned by participants.

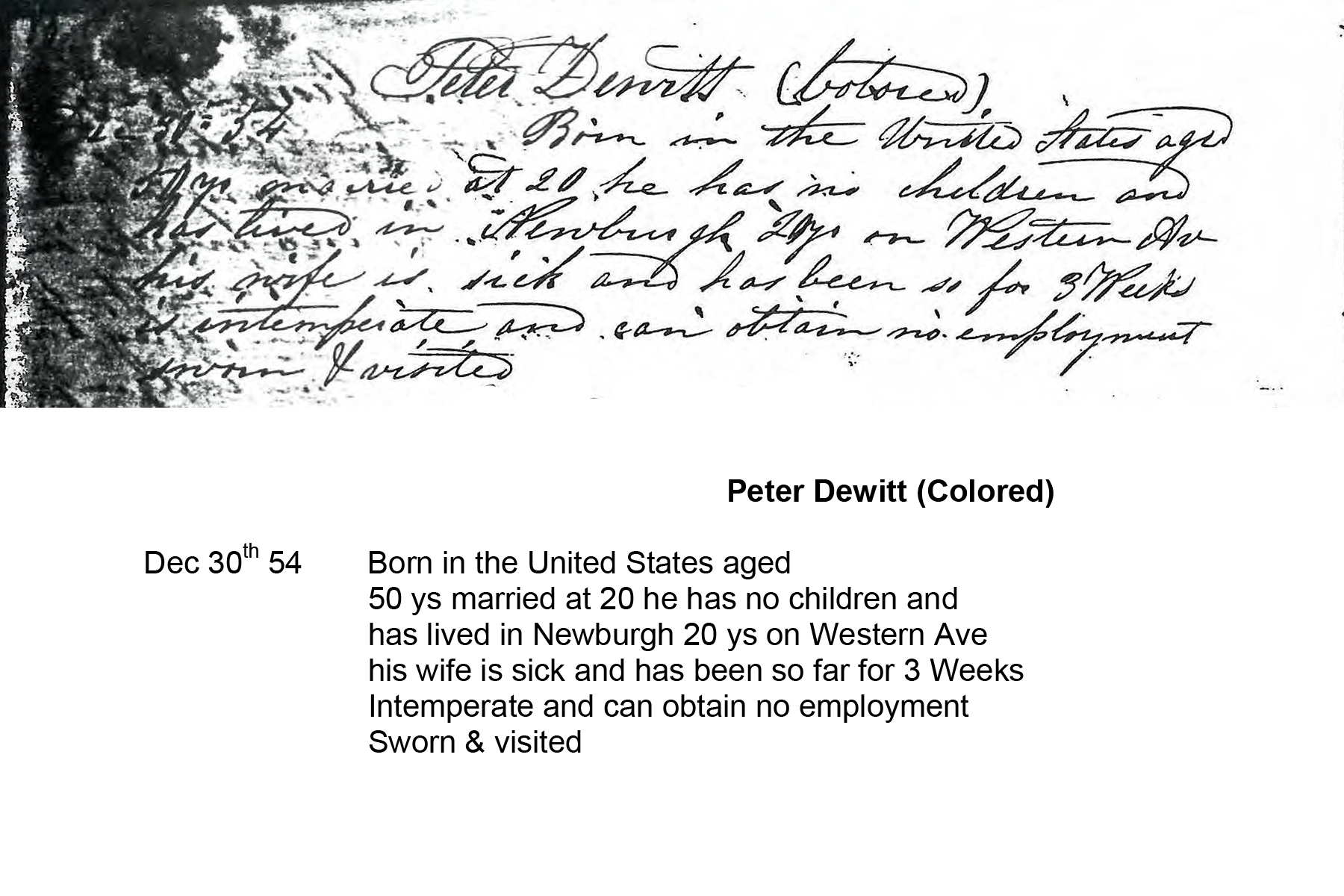

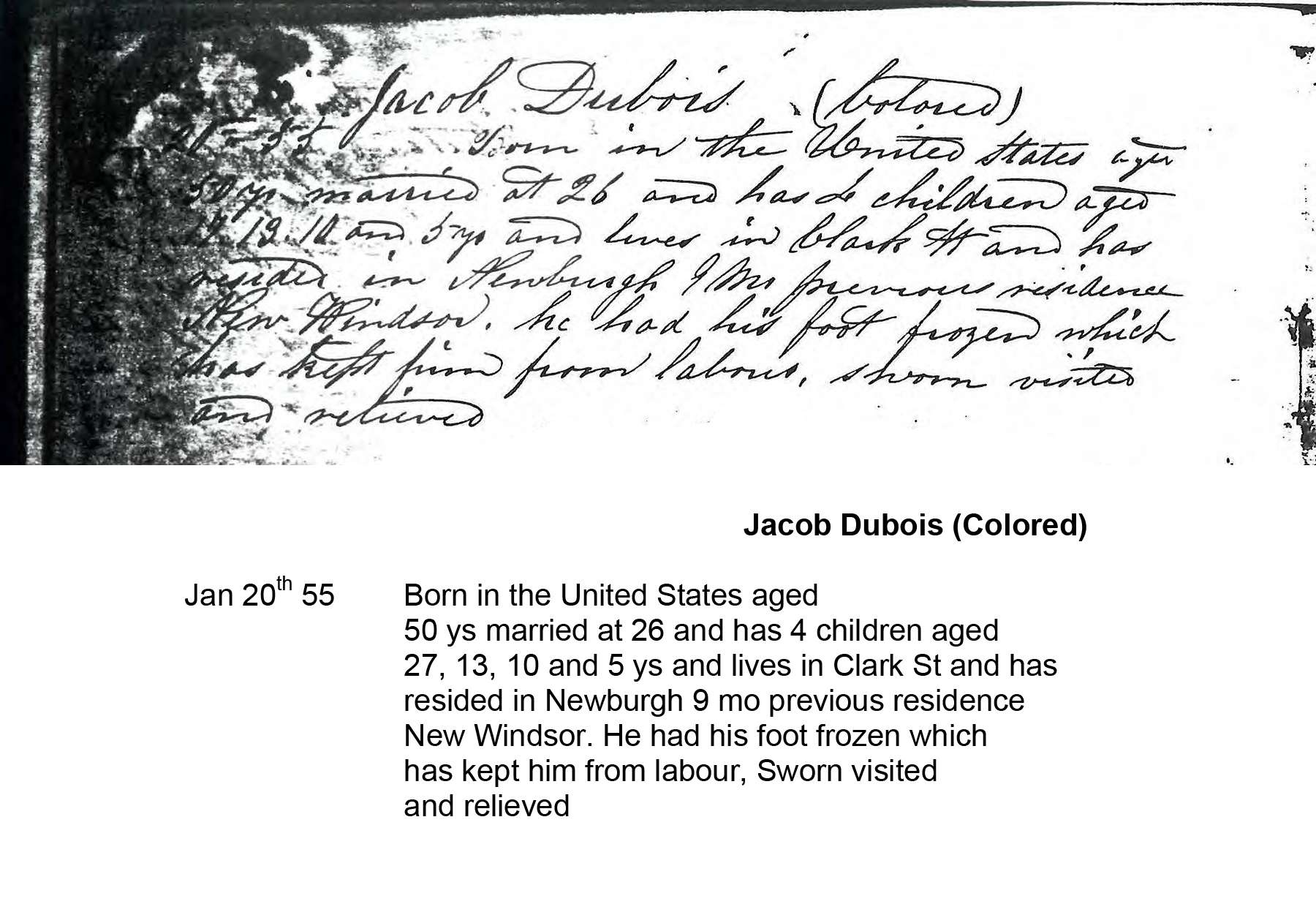

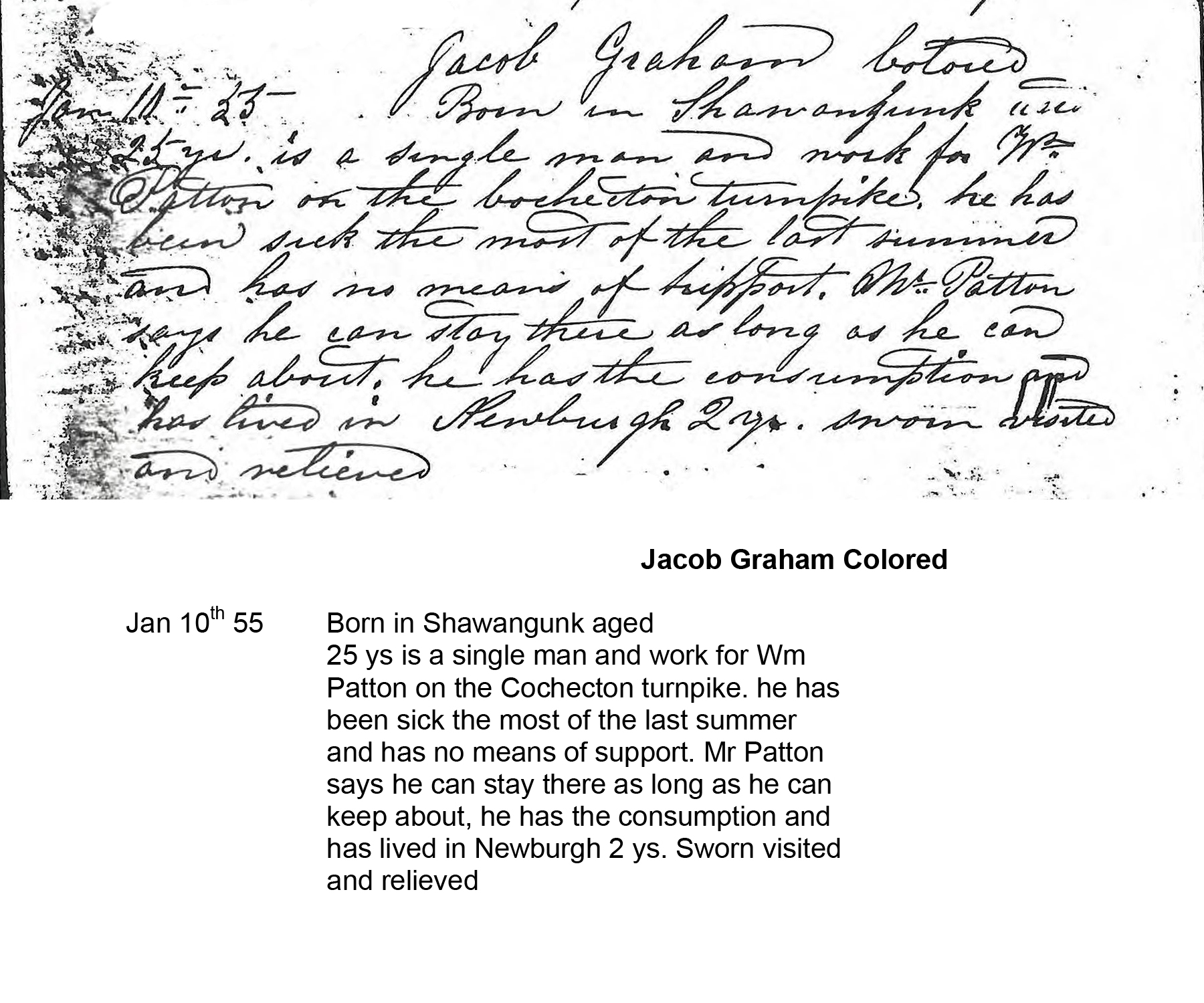

Examination Log Book cover, first page of index

Download full list PDF of scanned entries and transcriptions below

Download full list PDF of scanned entries and transcriptions below

Note: Original entry for Mary Turner is missing

People associated with the Almshouse, specifically making an application for burial, and therefore can most closely be associated with the "Colored Burial Ground.

Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s

Examination Log Book,

1853-1858

The Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book is the closest thing there may be to a cemetery record for the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground. In it, we find the names of those women, children and men designated as “Colored” who presented themselves to the Almshouse (or Poorhouse) in Newburgh. According to Dr. Christina Ziegler-McPherson, historian and co-author of The Archaeology, Osteology, and History of the Newburgh Colored Burial Ground, “[i]t is probable that African Americans [in Newburgh] buried their dead first at the alms house cemetery, and then after 1831 on Western Avenue.” It is also probable that those names recorded in the Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book could be associated with those (repeatedly) forgotten burials at Newburgh’s Colored Burial Ground.

The entries in Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book read like miniature biographies of lives that closely intersected with the antebellum years bookended by New York’s Gradual Abolition of Slavery and the Civil War. Of particular note were the names of those this project referred to as “Elders” – those born before, and excluded from, New York’s Gradual Emancipation Act passed in 1799 who were expected to remain enslaved for the rest of their lives. Many of the names include those asking alms (relief) for the burial of their loved ones, or perhaps even themselves.

In memory of Newburgh Colored Burial Ground’s once-named, we

say their names:

Peter Allen, Born 1776

Phebe Colden, Born 1749

John Coon, Born 1788

Margaret Currington, Born 1794

Susan Decker, Born 1795

Elizabeth Dubois, Born 1798

Margaret Johnston, Born 1786

Frances Johnston, Born 1786

Mary Moore, Born 1798

Dianna Raiment, Born ca. 1776

Jane Richardson, Born 1773

Lewis Robinson, Born 1769

John Schoonmaker, Born 1792

Mary Ann Smith, Born 1787

Lilly Stevens, Born 1790

Margaret Tuthill, Born 1789

Hannah Van Vacken, Born 1790

Philis Watson, Born 1796

Phebe Colden, Born 1749

John Coon, Born 1788

Margaret Currington, Born 1794

Susan Decker, Born 1795

Elizabeth Dubois, Born 1798

Margaret Johnston, Born 1786

Frances Johnston, Born 1786

Mary Moore, Born 1798

Dianna Raiment, Born ca. 1776

Jane Richardson, Born 1773

Lewis Robinson, Born 1769

John Schoonmaker, Born 1792

Mary Ann Smith, Born 1787

Lilly Stevens, Born 1790

Margaret Tuthill, Born 1789

Hannah Van Vacken, Born 1790

Philis Watson, Born 1796

The names of Black Newburgh residents recorded in The

Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book also serve as an

indictment of the violence in the form of charity that was exemplified by Newburgh’s

“Overseers of the Poor” who oversaw Newburgh’s Almshouse and presumably, the

Newburgh Colored Burial Ground. The Overseers of the Poor, in cooperation with the city’s law

enforcement, created the environment in which the lives of those recently

emancipated from, and immiserated by slavery could be criminalized for a

variety of “causes of poverty”, a selection of which are listed below:

Not over anxious to work

Has been in jail during the summer as a vagrant

Sent to the Alms House by the Police Justice as a vagrant

Laziness

Intemperance

Improvidence

Was a slave for many years

Can obtain no employment

Could give no cause for poverty

Has the reputation of being a very bad negro

Has been in jail for theft

Has no means of buying coal

Has no relatives able to assist him

Has no means of support

Has no relatives able to support her

Is a widow

Is very lame

Has given birth to two bastard children

All her children are dead

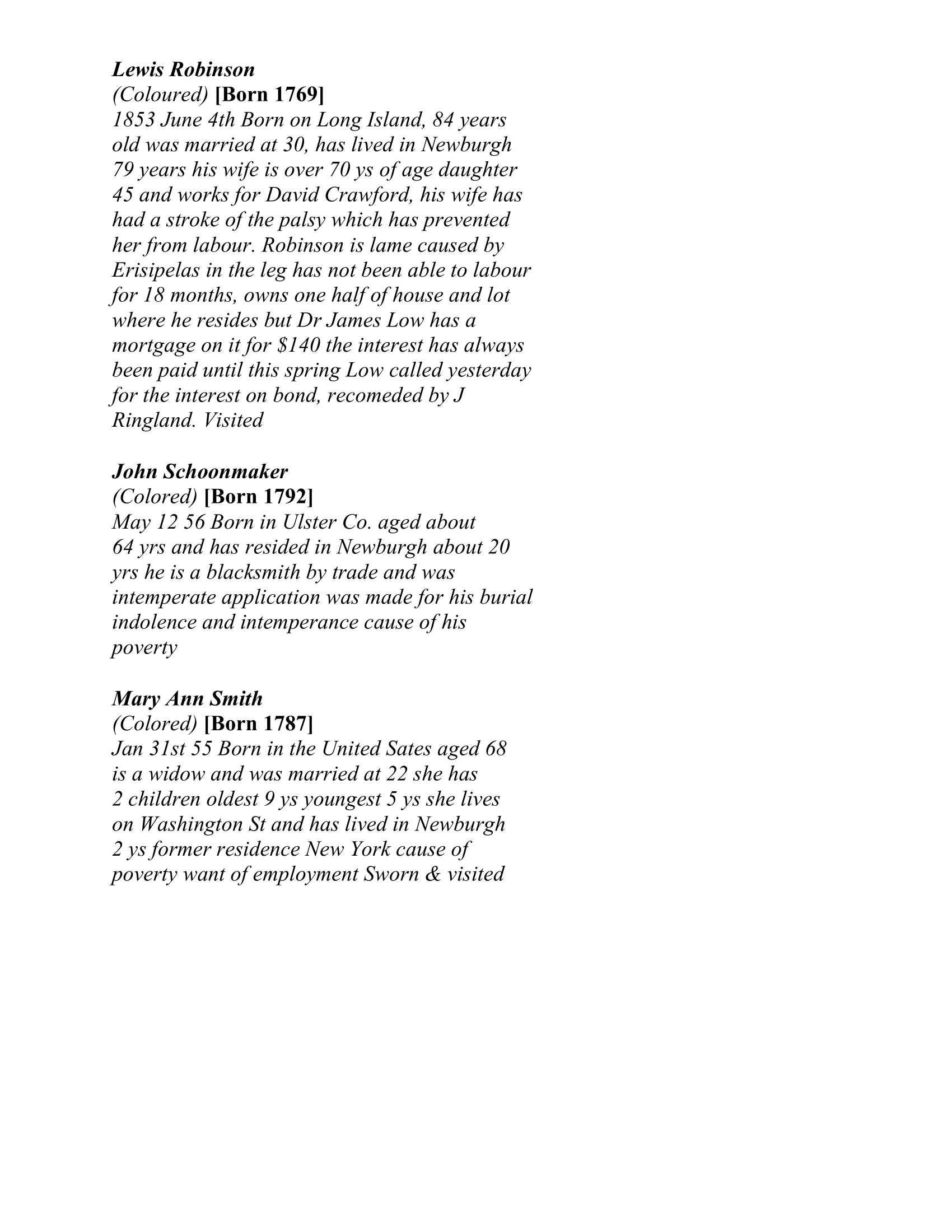

A Black New Yorker born after July 4, 1799 could “still be

the servant of the legal proprietor of his or her mother, until such servant if

male shall arrive at the age of twenty eight years, and if a female at the age

of twenty five years.”* However, the

children of the enslaved could be legally “abandoned” by their slave holders, a

process by which “every child abandoned […] shall be considered as paupers of

the respective Town or City […] and liable to be bound out by the Overseers of

the Poor.”* This Act convinced former slaveholders they weren’t losing what

they thought of as “property” but instead were benefitting from what Dr. David

Gellman calls “entitlement to servitude”**

The Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log

Book painfully documents the reality of the gradual abolition of slavery in

New York, which, rather than abolishing, reinvented slavery by another name:

that of servitude. In this manner, reparations were paid not to the enslaved,

but rather those slave holders who could be incentivized to relinquish the most

unappealing aspects of slavery (care for the enslaved) and still benefit from

the profits of free (or otherwise heavily subsided) labor. With the cooperation

of towns’ and cities’ Almhouses, by 1827 New York had fully developed a

prototype for the type state-sponsored criminalization of Blackness and poverty

that the rest of the country would not see until the post-Reconstruction era

with the advent of convict-leasing programs. In this light, the emancipation of

Black New Yorkers appears less as a miracle and more like the status quo.

A sincere debt of gratitude is owed to Michael Van Der Voort, Montgomery’s SPOMA (Sacred Place of My Ancestors) Committee member who brought this important historical record into this project’s fold. Mr. Van Der Voort has compiled much a wealth of data from the Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book.

* Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the New York Legislature, March 29, 1799

** Emancipating New York, David Gellman

A sincere debt of gratitude is owed to Michael Van Der Voort, Montgomery’s SPOMA (Sacred Place of My Ancestors) Committee member who brought this important historical record into this project’s fold. Mr. Van Der Voort has compiled much a wealth of data from the Newburgh Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book.

* Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the New York Legislature, March 29, 1799

** Emancipating New York, David Gellman

Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County, New York cover, acknowledgements, and introduction

Genealogy of Black Families

of Orange County, New York

by Robert W. Brennan, published by the

Orange County Genealogical Society

This voluminous work was compiled thanks to the labor of a sincerely devoted local genealogist who posed a seemingly simple question; “How does a young [B]lack person get started [in their research]?" when considering “the scarcity of material on local [B]lack history here in Orange County.” Compiling and cross-referencing such primary source materials as local, State and Federal census records, marriages, obituaries, and Civil War records, Robert Brennan’s stated goal “to provide a starting point for a person of African-American heritage […] in their research” has resulted in a database of over 2,200 individuals; a significant testament to this goal’s achievement.

Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County served as a valuable resource in researching several names of individuals who may have also been buried in Newburgh Colored Burial Ground, most notably, members of the Dolson family.

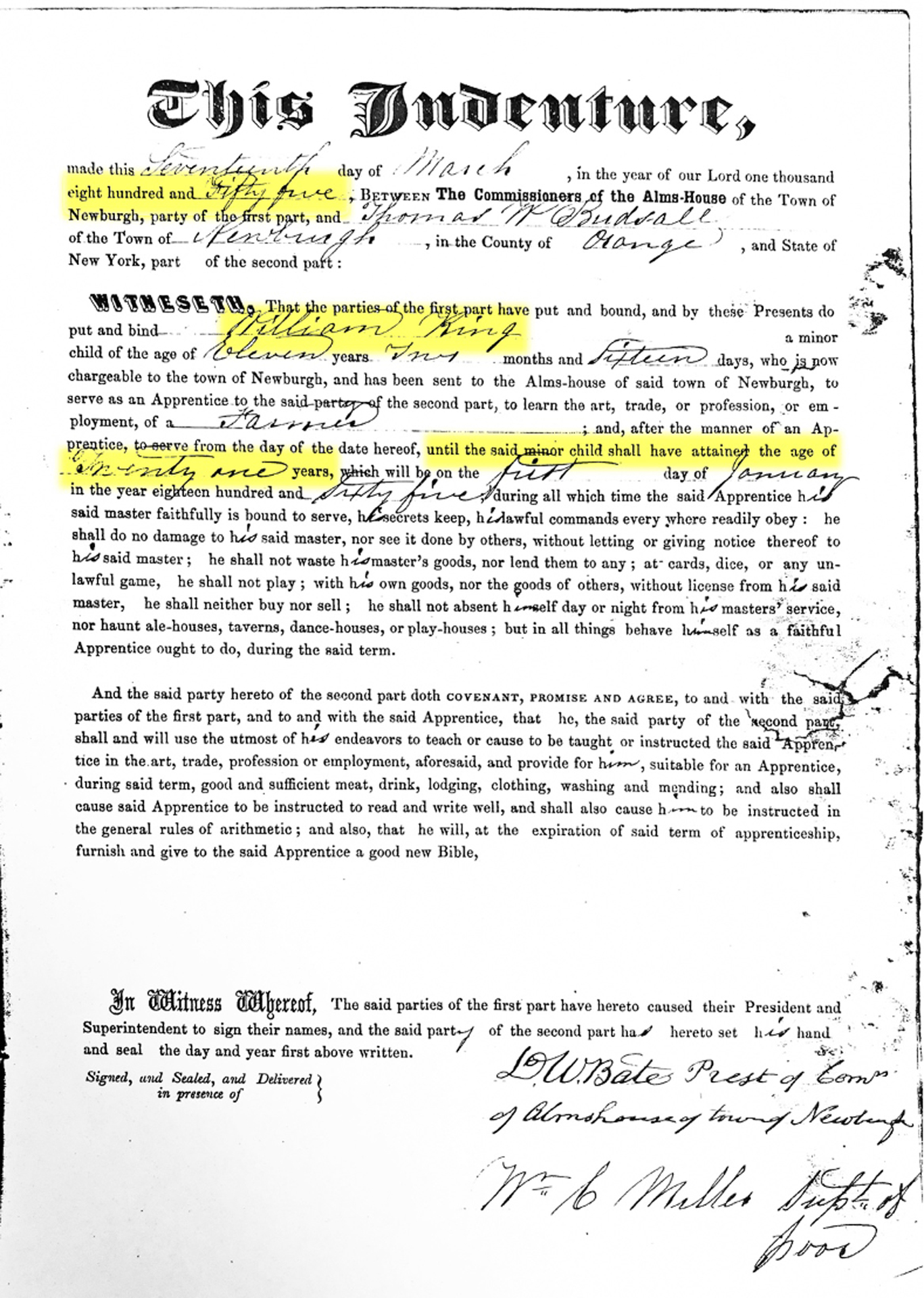

William King/Dolson Jr., born 1842

Under “Descendants of William Dolson” (page 24) Genealogy

of Black Families of Orange County lists the first generation of children

born to William Dolson and Maria King who also appear in the Newburgh

Almshouse Commissioner’s Examination Log Book, along with two of their

children, William Dolson Jr. and Albert Dolson.

When cross-referencing the sources above, both William

Dolson Jr. and William King are listed as the son of William Dolson and Maria

King. Since according to these records, they also share the same year of birth,

it can be assumed that William Dolson Jr. and William King are the same person.

After having been charged In 1853 as vagrant at the age of 9 and taken to the

Almshouse, later, in 1855, William King shows up in an indenture to a Thomas

Budsall for a period of “apprenticeship” as a farmer for 10 years, or until

1865, when he would have turned 21.

Instead, we know that William Dolson Jr. released himself from his indenture to Thomas Budsall at the age of 19, two years early, to enlist in the 14th Rhode Island Regiment in 1863.

Instead, we know that William Dolson Jr. released himself from his indenture to Thomas Budsall at the age of 19, two years early, to enlist in the 14th Rhode Island Regiment in 1863.

Albert Dolson, b. July 04, 1847, Newburgh, NY; d.

September 27, 1934, Washingtonville, NY

While it is not yet known how many of the seven children of

William Dolson and Maria King survived childhood, there is a wealth of

information about their fifth child, Albert Dolson, thanks to Genealogy of

Black Families of Orange County. Sadly, we know that in 1858, at the

age of 10, Albert Dolson suffered the

same fate as his brother William and was sent to the Almshouse after his

mother, Maria King, had died. Had she been in the care of the Almshouse in her

remaining years, she (and any of her children who did not reach adulthood) can

be expected to have been buried in Newburgh’s Colored Burial Ground.

Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County includes

an obituary for Albert Dolson from the Orange County Newspaper from September

1934 which describes Albert Dolson, who lived to the ripe age of 92 years, as

“formerly employed by the Cemetery Association in Washingtonville[.]” Having

witnessed the death, and perhaps the burial, of his mother at such a young age,

one can only wonder whether it had an influence on Albert Dolson’s occupation of

honorably laying his community’s departed loved ones to rest.

The legacy of William Dolson and Maria King are the generations of Dolsons whose names still fill attendance sheets at Newburgh’s City School District to this day. Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County is an excellent resource that has proven invaluable in providing a link to the descendant community that can be associated with Newburgh’s Colored Burial Ground.

Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County, New York, by Robert W. Brennan, published by the Orange County Genealogical Society**, who generously allowed selected portions to be reproduced here.

**Orange County Genealogical Society, 101 Main St. Goshen, New York

The legacy of William Dolson and Maria King are the generations of Dolsons whose names still fill attendance sheets at Newburgh’s City School District to this day. Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County is an excellent resource that has proven invaluable in providing a link to the descendant community that can be associated with Newburgh’s Colored Burial Ground.

Genealogy of Black Families of Orange County, New York, by Robert W. Brennan, published by the Orange County Genealogical Society**, who generously allowed selected portions to be reproduced here.

**Orange County Genealogical Society, 101 Main St. Goshen, New York

From the Ground UP is made possible with support from:

![]()

![]()